But Are Media Better Since Central Park Case?

Letter: Most Gun Violence Isn’t Just ‘Local News’

Support Journal-ismsDonations are tax-deductible.

But Are Media Better Since Central Park Case?

It took years for this statement to materialize: “I cannot and will not defend local media’s coverage of the Central Park Five, the Exonerated Five case,” said Dan Shelley, president and CEO of the Radio Television Digital News Association. He was talking about the five Black and brown teenagers who were falsely accused — and convicted, after coerced confessions — in the horrific 1989 rape of a white female jogger in New York’s Central Park.

Now the five have been exonerated, and come January, one of them, Yusef Salaam, is to join the New York City Council. He all but won the Harlem seat over the summer, receiving nearly 64 percent of the vote in the Democratic primary.

The young men’s convictions had been vacated in 2003, after they had already served from seven to 13 years behind bars.

A 2014 Journal-isms column on the widely covered case was headlined, “Will the Media Ever Apologize?” At the time, a PBS documentary was about to air. “Filmmakers Sarah and Ken Burns, not to mention the Central Park Five, think it’s time for someone to apologize,” David Hinckley began a piece about the film in New York’s Daily News.

In a video posted last year, Raymond Santana talks about being falsely convicted, his disappointments, joys, fears and what it took to be at peace. (Credit: “Pierre’s Panic Room”/YouTube)

“The ‘someone’ might be news media members who abandoned their skepticism and went for what they believed the best storyline, helping to ruin lives as they convicted the suspects with their headlines, commentary and television scripts,” this column explained.

The RTDNA’s Shelley (pictured) continued, “Back when the crime happened, during the subsequent judicial proceedings, and even to this day — . . . in retrospect, many mistakes were made, many ethical breaches occurred. I think that journalists of that era probably did cause a lot of harm through their coverage.”

The RTDNA’s Shelley (pictured) continued, “Back when the crime happened, during the subsequent judicial proceedings, and even to this day — . . . in retrospect, many mistakes were made, many ethical breaches occurred. I think that journalists of that era probably did cause a lot of harm through their coverage.”

Shelley turned to Elinor Tatum, editor and publisher of the New York Amsterdam News, which had maintained the youths’ innocence from the beginning. “I don’t excuse, Elinor, for one moment, the fact that no one gave the Amsterdam News and other Black media outlets credit for saying, ‘We told you so’ when the exonerations occurred. But I will say this: the industry is hyper-focused on these kinds of issues today.

“The industry is trying to make some significant improvements. It starts with hiring more people of color to staff local newsrooms so that they truly reflect the communities that they serve. We’ve seen significant, but not significant enough improvement in that area, particularly post-George Floyd, and post-2020, in the racial reckoning that occurred as a result of his death and the death of too many others.

“I will also tell you that a lot of thought and a lot of introspection is occurring in the local television news industry. . . .”

Shelley and Tatum were part of a Journal-isms Roundtable held by Zoom on July 31. Forty-two people were on the call; another 72 watched on Facebook and 96 had tuned in to the YouTube version as of Labor Day. You can watch the embedded recording above or on the YouTube site.

The question on the floor was whether crime coverage had improved since then. The majority said that if it had, it was only slightly, and some called for reframing the whole notion of crime reporting. What is the point? How does it help communities?

Still, Brenda Wilson (pictured), a retired NPR reporter living in Washington, messaged afterward, “I’m a lot more optimistic than I was before I tuned in.” That’s “because people — Black journalists, mainly — are thinking about crime and how it should be covered and I heard really great ideas in how it should be dealt with, in a way that is responsible and addresses the needs and concerns of the African American community.

Still, Brenda Wilson (pictured), a retired NPR reporter living in Washington, messaged afterward, “I’m a lot more optimistic than I was before I tuned in.” That’s “because people — Black journalists, mainly — are thinking about crime and how it should be covered and I heard really great ideas in how it should be dealt with, in a way that is responsible and addresses the needs and concerns of the African American community.

“I was deeply disturbed and saddened by the killing of a Black father who had been a kind and giving soul in the community, and the stabbing of another who was just going to work early in the morning. The killing [at Catholic University] within the same general area was just as disturbing.

“But as I said, I wonder about the young, I presume, people involved in the attacks and worried about what has left them so bereft of their humanity.”

That’s a question many called more important than the weekend body count that greets many news consumers each Monday.

In addition to Shelley and Tatum, speakers included David P. Kreizer, an attorney for Korey Wise of the now Exonerated Five; The Marshall Project’s Carroll Bogert, who is president, and Susan Chira, editor-in-chief; Letrell Crittenden, Ph.D, director of inclusion and audience growth at the American Press Institute; and Collette Watson, director, and Diamond Hardiman, reparative journalism program manager, of the Media 2070 project of the Free Press advocacy organization on media matters.

We also toasted Andale Gross, newly named managing editor of the Kansas City Star, who completed a nearly four-year stint as race and ethnicity editor at the Associated Press.

Kreizer (pictured) was only 9 years old at the time of the jogger case, he said.

Kreizer (pictured) was only 9 years old at the time of the jogger case, he said.

“The interesting thing is you fast-forward to 2008, 2009, when I was approached with [lawyers] Jane H. Fisher-Byrialsen, and her husband David Fisher, to represent Korey. I had no idea that they were even exonerated . . . the media was so frenzied and so much about making this story, and then when the truth finally came out . . . the same person who at 9 years old knew everything about the case . . . had no idea that they actually didn’t do it. It took me being approached as an attorney to find that out. And I thought that was sort of very telling of media coverage. . . .

“But to answer the specific question, has it improved since 1989, 1990? I would say it has improved, but I would use the word ‘mildly’ because I think society as a whole, we still love that sensational story. We still love to hear what happened or to have that ‘we got the guy’ moment, and I think the media, to some extent, feeds into that. At least in New York, we still love our perp walk, right?”

Tatum (pictured) added, “The way the media hung on to it, and created the whole term ‘wilding’ from it, was disgusting. And the fact of the matter is, to this day, they will still — the media — and unfortunately, it continues to happen. If they find somebody that they can attack and blame that cannot defend themselves, they will continue to do it. And unless there are outlets that will not go along for the ride, and will be the better part of wisdom and will be that voice, it will continue to happen. . . .”

Tatum (pictured) added, “The way the media hung on to it, and created the whole term ‘wilding’ from it, was disgusting. And the fact of the matter is, to this day, they will still — the media — and unfortunately, it continues to happen. If they find somebody that they can attack and blame that cannot defend themselves, they will continue to do it. And unless there are outlets that will not go along for the ride, and will be the better part of wisdom and will be that voice, it will continue to happen. . . .”

There are more journalists of color in newsrooms now than during that media frenzy, but Gross (pictured below) said that wasn’t enough.

“The thing that I learned about race coverage, that I didn’t think too much about when I got the role” of race and ethnicity editor at the Associated Press, “was just how much I would have to push, and my team would have to push, to get taken seriously about wanting to tell one of the more in-depth stories about racial disparities, systemic racism, how racism permeates every institution you can even think of, you know, from hospitals to schools, from financial institutions to the military.

“The thing that I learned about race coverage, that I didn’t think too much about when I got the role” of race and ethnicity editor at the Associated Press, “was just how much I would have to push, and my team would have to push, to get taken seriously about wanting to tell one of the more in-depth stories about racial disparities, systemic racism, how racism permeates every institution you can even think of, you know, from hospitals to schools, from financial institutions to the military.

“There seemed to always be an appetite for stories that were reactionary, and reacting to racist incidents, and things like that, but when it came time to really dig into the more in-depth that we wanted to do, there was always — we had to get buy-in for it. I think over time we wore folks down, and they started to believe in what our own vision for ourselves was, and that led to some really great projects, like Kat Stafford’s “Birth to death: A lifetime of disparities among Black Americans.”

The nonprofit Marshall Project, launched in 2014 and named after Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, seeks through its reporting “to create and sustain a sense of national urgency about the U.S. criminal justice system.”

Editor Chira (pictured) told the group, “We put together a list of principles that we shared with other news media, a guide to what language to use and avoid when referring to people in the criminal justice system, because one of the lessons of the Exonerated Five is that if you dehumanize people, if you equate them to animals, or in other ways deny their humanity, it’s very easy to demonize them and think of them as not human. . . .

Editor Chira (pictured) told the group, “We put together a list of principles that we shared with other news media, a guide to what language to use and avoid when referring to people in the criminal justice system, because one of the lessons of the Exonerated Five is that if you dehumanize people, if you equate them to animals, or in other ways deny their humanity, it’s very easy to demonize them and think of them as not human. . . .

“You try to think about what tools you can use to help people who may not realize . . . that some words that sound neutral to them, are actually experienced as insults. . . . For an example, there’s disagreement about it, but we avoid the word ‘inmate.’ Some people may think that’s very neutral, but we heard from people who were incarcerated. In many cases the corrections officers would shout at them and use the word ‘inmate’ or their number as a way of dehumanizing them. [‘Inmate’] brought up those memories. . . .”

In addition, Chira said, “One of the things you learn when you cover crime is that despite what politicians say, criminologists and other people who study this have never been able to satisfactorily explain the causality. What really causes crime rates to rise or drop? . . . So we tried to really look at what the data said and what it didn’t say. And we have also made a huge effort to spread that in local markets, where . . . they don’t necessarily have the access to some of the data analysis that we’re able to do. So that for example, one of our reporters analyzed the national crime statistics collected yearly by the FBI.

“And the FBI had changed to a new system, and lo and behold, in the first year of the system, a massive percentage, almost 40 percent, of major police departments, did not in fact, and were not able to submit data, or they did not submit data to the FBI crime statistics. So those crime statistics left out many of the major cities and major states in the country. . . .”

First Bogert (pictured), and then Crittenden of the American Press Institute emphasized the value of community ties. “I’m from Chicago and I happened to look into the Chicago Tribune and the Chicago Defender [of the Black press], and how they covered this era differently,” Bogert said. And I spoke to one of the people who covered crime for the Chicago Defender at the time, and he said we would never have used the word ‘superpredator,’ “

First Bogert (pictured), and then Crittenden of the American Press Institute emphasized the value of community ties. “I’m from Chicago and I happened to look into the Chicago Tribune and the Chicago Defender [of the Black press], and how they covered this era differently,” Bogert said. And I spoke to one of the people who covered crime for the Chicago Defender at the time, and he said we would never have used the word ‘superpredator,’ “

“Never! Interesting take on that: He said the Chicago Defender, its offices were in the neighborhood. ‘I was on the second floor, people could actually reach up to the window where I sat, and knock on it if they didn’t like my coverage.’ “

Crittenden (pictured) mentioned the “Inclusion Index” he created. When applied to Pittsburgh, the index found in February that, “Residents of color expressed feelings of deep distrust for local media across the board. This has been intensified by a significant number of public occurrences over the past eight years. These include offensive editorials and columns, public mistreatment of reporters of color, racist statements made by local reporters and questionable decisions related to coverage of communities of color.”

Crittenden (pictured) mentioned the “Inclusion Index” he created. When applied to Pittsburgh, the index found in February that, “Residents of color expressed feelings of deep distrust for local media across the board. This has been intensified by a significant number of public occurrences over the past eight years. These include offensive editorials and columns, public mistreatment of reporters of color, racist statements made by local reporters and questionable decisions related to coverage of communities of color.”

Crittenden told the group, what “we need is systematic reforms on how we actually go about beat coverage . . . much more community engagement and listening to the community.”

Cheryl Phillips, faculty director at the Stanford Computational Policy Lab, and Alain Stephens, West Coast correspondent at The Trace, speak at the 2023 Crime Coverage Summit, presented in San Diego by the Radio Television Digital News Association and the National Press Foundation and sponsored by Arnold Ventures.

Shelley agreed, noting that in January, RTDNA co-sponsored a three-day forum in San Diego with the National Press Foundation.

He shared two takeaways: “Number one, do more contextualizing in crime coverage; get beyond the sensationalism that can exist in local crime coverage, and provide more context. . . .Yes, there were upticks in certain kinds of crime during and after the pandemic, but overall, crime rates were down. So provide that context in your coverage, or similar context in your coverage.

“Another takeaway was, commit that if you start following a crime, if you start reporting on a crime from the beginning, you make a commitment and follow through on that commitment to report on that crime all the way to its conclusion, no matter how many years it may take. That’s a big commitment for local newsrooms to make, but many are now making it.”

Moreover, don’t go into Black communities only when police scanners point reporters in that direction. (A related issue: Many jurisdictions are trying to curb public and media access to these scanners, a trend RTDNA and others are fighting.)

Wanda Lloyd (pictured), a former top editor with the Gannett Co. in Greenville, S.C., and Montgomery, Ala., emphasized the importance of leadership. “We realized that just having the photograph and the stories of whoever was arrested overnight for whatever crime, whether it was a shooting or robbing or car accident, and running the mug shots on page one was doing harm to the community and it did speak to that psyche in our community. . . . I made a leadership decision that we were going to take the mugshots of all criminals except for those who are at large and a threat to society off of page one. . . .

Wanda Lloyd (pictured), a former top editor with the Gannett Co. in Greenville, S.C., and Montgomery, Ala., emphasized the importance of leadership. “We realized that just having the photograph and the stories of whoever was arrested overnight for whatever crime, whether it was a shooting or robbing or car accident, and running the mug shots on page one was doing harm to the community and it did speak to that psyche in our community. . . . I made a leadership decision that we were going to take the mugshots of all criminals except for those who are at large and a threat to society off of page one. . . .

“That really made a difference. The other thing we did, though, is in both communities, I hired a bus, I got a bus and a historian and took them into the Black community, the entire staff took two or three busloads to do this over time.

“I paid a historian to just talk about the rich, the richness of the Black communities because so many of our non-Black staff members were afraid to go into the community unless they were covering crime and they didn’t really know about the rich stories and the fact that the families there who were, you know, maybe some of them were in service jobs, but really working really hard to make sure that kids got a good education and got a fair shake in society and that they didn’t end up on page one in a criminal — in a crime story.”

The observation dovetailed into points made by Watson and Hardiman of the Media 2070 project, so named because, as the Columbia Journalism Review explains, “The year 2070 is a deadline, of sorts – the group’s goal is to have completely transformed the media industry by then.”

Media 2070 calls “for the top 10 print and broadcast media outlets as defined by reach to devote at least 10 percent of their pretax profits to a fund to support Black and ethnic media to redress decades of racially biased funding,” Watson (pictured) said. “We believe that . . . philanthropic foundations should double their commitment to the journalism field overall.”

Media 2070 calls “for the top 10 print and broadcast media outlets as defined by reach to devote at least 10 percent of their pretax profits to a fund to support Black and ethnic media to redress decades of racially biased funding,” Watson (pictured) said. “We believe that . . . philanthropic foundations should double their commitment to the journalism field overall.”

Moreover, “We should take a fundamental look at the crime beat and be curious about why it even exists. . . . We have to ask ourselves, does a so-called crime beat compel media organizations to fill a quota of crime stories, regardless of what’s real in our communities?

“We’re asking, ‘What is the information that’s actually needed to close gaps and correct injustice?”

Her colleague, Hardiman (pictured), mentioned a bonus: “We can have the stories that we need so that journalism can be an enjoyable process for the Black journalists doing it and the people that are reading it and experiencing it. Collette’s right on about rethinking the crime beat and the way that it even functions and how that impacts Black people and how it’s connected to a larger system and institution of ways of oppressing people.”

Her colleague, Hardiman (pictured), mentioned a bonus: “We can have the stories that we need so that journalism can be an enjoyable process for the Black journalists doing it and the people that are reading it and experiencing it. Collette’s right on about rethinking the crime beat and the way that it even functions and how that impacts Black people and how it’s connected to a larger system and institution of ways of oppressing people.”

Tatum agreed. In July 2022, the Amsterdam News launched a series, “Beyond the Barrel of the Gun,” to raise awareness of how gun violence can be reduced in Black and Brown communities in New York City and nationwide. “We’re trying to bring that to Black newspapers across the country and to other places as well,” she told the group.

“After we launched ‘Beyond the Barrel of the Gun,’ we wanted to go from ‘If it bleeds it leads’ to solutions,” Tatum added.

Both a perpetrator and victim of violence, the younger version of Dedric Hammond ended up spending eight years in prison, according to the New York Amsterdam News. He was known then as “Bad News,” but today he is “Be-Loved,” the subject of a 26-minute documentary from the newspaper that follows this “credible messenger” through Harlem as he works with young people. Instead of a routine story about how many were shot over the weekend, the Amsterdam News put Be-Loved on its front page. (Credit: Andre Lamberston via Amsterdam News)

“And instead of having something about how many people were shot during Fourth of July weekend, we went to ‘What are the solutions to these shootings in New York City? How can we make a difference? How can we make a change?” And so we put on the front page a person who was making a difference. And it was all about a documentary that we had just put together for the Amsterdam News and for ‘Beyond the Barrel of the Gun.’ About a guy named Be-Loved who used to be involved in gun violence and now was stopping gun violence.

“It’s very important that we change that narrative, that we change, we reframe the discussion on gun violence because if we don’t, we’re going to continue to have these headlines that just keep people doing the same thing over and over again.

“We’ve got to go away from ‘if it bleeds it leads’ because . . . it’s not going to change the way people look at our communities, because when they look at our communities as a place of violence, it’s just going to continue that cycle. And it’s going to continue the stigma and continue the generational trauma that has been imposed on our psyches.”

- Emily Barr, TVNewsCheck: Going Beyond ‘If It Bleeds It Leads’ (Jan. 25)

- Geoff Bennett, “PBS NewsHour”: Exonerated member of ‘Central Park Five’ on his historic city council primary win (July 3)

- Tauhid Chappell and Mike Rispoli, NiemanLab: Defund the crime beat (December 2020)

- Chronicle of Philanthropy: Philanthropy’s Push to Stop Gun Violence

- Diamond Hardiman and Collette Watson, Buffalo News: It’s time to explore how the media plays a role in race-based violence (Aug. 13)

- German Lopez, New York Times: A Continuing Drop in Murders (Dec. 30)

- The Marshall Project: Witnesses: Yusef Salaam, One of the Central Park Five (video)

- Kelly McBride, Poynter Institute: Local newsrooms want to stop sensationalizing crime, but it’s hard (April 11)

- Media 2070: We’re Calling on Newsrooms and Media Organizations to Pledge to Care for Black Communities and Journalists (April 29, 2021)

- Media 2070: The Moment is Magic: 7 Tips for Journalists from Restorative-Justice Practitioners [PDF]

- Feven Merid, Columbia Journalism Review: Q&A: Media 2070’s Collette Watson on the movement for media reparations (July 26)

- Carla Murphy, Dissent: Multiple Mainstreams: Only public investment will deliver a media that can serve the news needs of our time.

- Harry Parker, Janon Fisher and Thomas Tracy, Daily News, New York: Majority of New Yorkers are worried about becoming crime victims; many have bought a gun for protection: poll (July 12)

- PublicSource: PublicSource maps and chronicles the strengths of diverse communities. (recommended by Letrell Crittenden)

- Dana Rieck and Josh Renaud, St. Louis Post-Dispatch: Homicides are down about 22% this year in St. Louis. Other reported crimes are down, too

- Gideon Taaffe, Media Matters for America: After fearmongering about crime, cable news networks are now largely ignoring decreasing homicide rates across the US (June 15)

Letter: Most Gun Violence Isn’t Just ‘Local News’

“A Belated Apology for Notorious Crime Coverage: But Are Media Better Since Central Park Case?”

Nope! It’s not better and could easily happen again, if circumstance conspires.

And the editorial myopathy/selectivity problem in the Central Park Case? is equally as bad on what other issues make the national news and how they are covered.

For example, I research gun violence (GV) and it’s clear to me that the U.S. media’s editorial decisions are a major factor in why most Americans lack the level of personal awareness with our gun violence problem needed to demand changes in our national gun laws. Our collective sense of urgency on GV is woefully out of step with the level of the challenge.

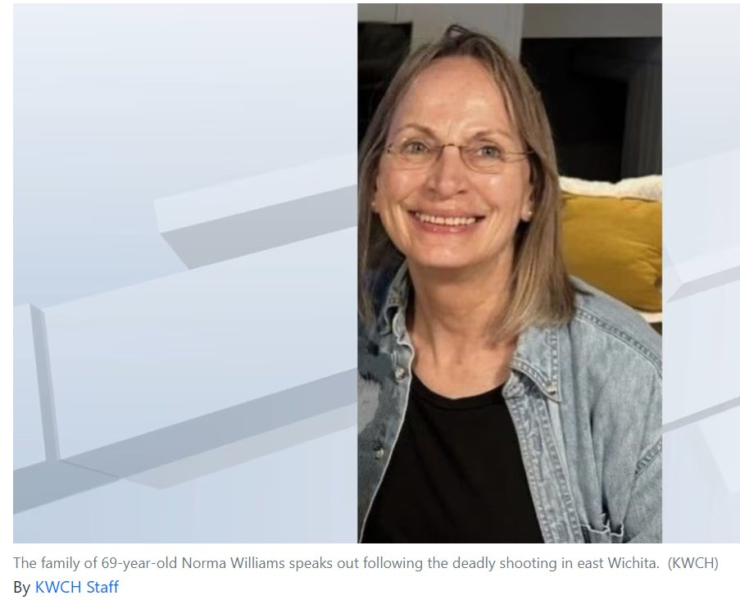

The story of Norma Williams is typical of the daily GV carnage most Americans never hear about, due to our media’s practice of covering most U.S. gun violence as “local news,” i.e. America writ large is blind to the scale of U.S. GV.

While it’s true every shooting is a local incident, it’s also true that gun violence is a National Problem. Too few of the far too numerous local GV stories like the outrageous Norma Williams story detailed below never make it into our national narrative on gun violence. At national level, GV is too often reported as summary level stats that simply don’t convey the level of preventable carnage America tolerates and what it is doing to us.

The national media needs to construct a framing narrative that links these local shootings into the compelling national issue that can arouse the public consciousness needed to demand change :

A 19-year-old motorcyclist and his buddies ran a red light and struck a vehicle that had the green light. The bikers then angrily pursue and shoot at the occupants of the vehicle, killing a vehicle passenger, 69-year-old Wichita resident Norma Williams. https://www.kwch.com/…/family-69-year-old-woman-killed…/

Clearly, Norma Williams, like Sierra Jenkins and so many other victims, are deserving of having more of us understand that they were victims of our irresponsible gun laws — and that such victims had the all-too-common misfortune of encountering a circumstance that could happen to anyone in the USA — that’s the national story that needs to be told and told again and retold until we address it.

Greg Fuller

Detroit

To subscribe at no cost, please send an email to journal-isms+subscribe@groups.io and say who you are.

Facebook users: “Like” “Richard Prince’s Journal-isms” on Facebook.

Follow Richard Prince on Twitter @princeeditor

Richard Prince’s Journal-isms originates from Washington. It began in print before most of us knew what the internet was, and it would like to be referred to as a “column.” Any views expressed in the column are those of the person or organization quoted and not those of any other entity. Send tips, comments and concerns to Richard Prince at journal-isms+owner@

View previous columns (after Feb. 13, 2016).

View previous columns (before Feb. 13, 2016)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2018 (Jan. 4, 2019)

- Book Notes: Is Taking a Knee Really All That? (Dec. 20, 2018)

- Book Notes: Challenging ’45’ and Proudly Telling the Story (Dec. 18, 2018)

- Book Notes: Get Down With the Legends! (Dec. 11, 2018)

- Journalist Richard Prince w/Joe Madison (Sirius XM, April 18, 2018) (podcast)

- Richard Prince (journalist) (Wikipedia entry)

- February 2018 Podcast: Richard “Dick” Prince on the need for newsroom diversity (Gabriel Greschler, Student Press Law Center, Feb. 26, 2018)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2017 — Where Will They Take Us in the Year Ahead?

- Book Notes: Best Sellers, Uncovered Treasures, Overlooked History (Dec. 19, 2017)

- An advocate for diversity in the media is still pressing for representation, (Courtland Milloy, Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2017)

- Morgan Global Journalism Review: Journal-isms Journeys On (Aug. 31, 2017)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2016

- Book Notes: 16 Writers Dish About ‘Chelle,’ the First Lady

- Book Notes: From Coretta to Barack, and in Search of the Godfather

- Journal-isms’ Richard Prince Wants Your Ideas (FishbowlDC, Feb. 26, 2016)

- “JOURNAL-ISMS” IS LATEST TO BEAR BRUNT OF INDUSTRY’S ECONOMIC WOES (Feb. 19, 2016)

- Richard Prince with Charlayne Hunter-Gault, “PBS NewsHour,” “What stagnant diversity means for America’s newsrooms” (Dec. 15, 2015)

- Book Notes: Journalists Follow Their Passions

- Book Notes: Journalists Who Rocked Their World

- Book Notes: Hands Up! Read This!

- Book Notes: New Cosby Bio Looks Like a Best-Seller

- Journo-diversity advocate turns attention to Ezra Klein project (Erik Wemple, Washington Post, March 5, 2014)