Reader Response Was, as Expected, Good and Bad

CBS Faults ‘Mornings’ Interview of Ta-Nehisi Coates

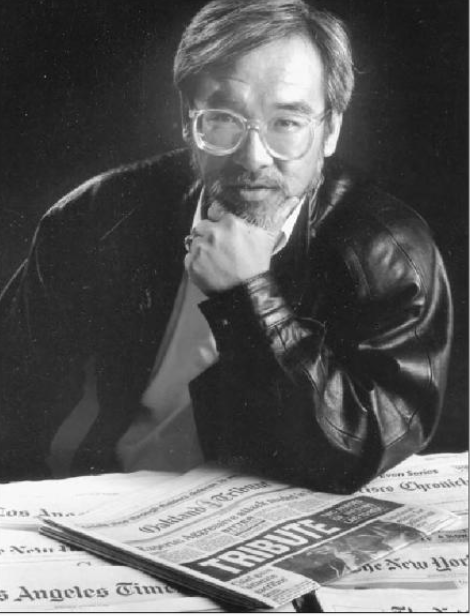

Homepage photo: William Gee Wong in his Tribune days, by the Oakland Artists Project

Support Journal-isms

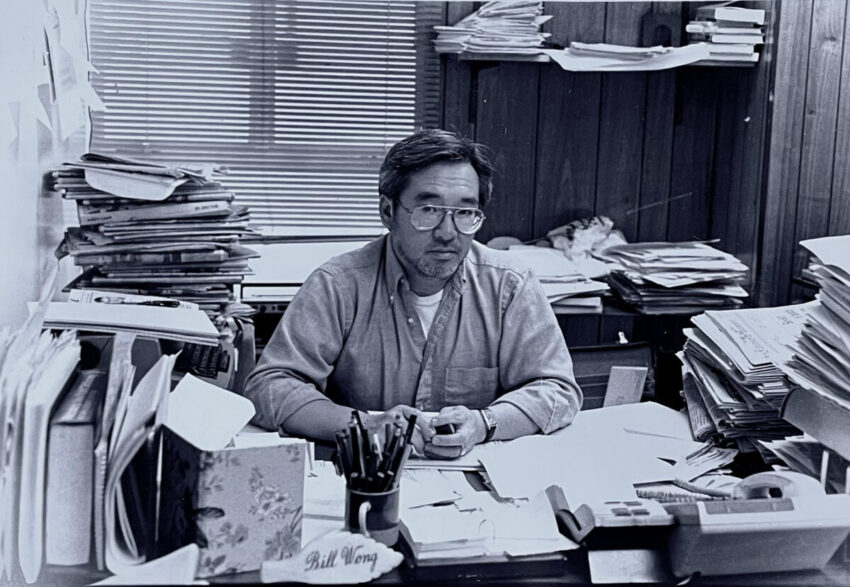

William Gee Wong at the Oakland Tribune in late 1980s or early 1990s. (Credit: Ron Kitagawa)

Reader Response Was, as Expected, Good and Bad

No account of the struggle to achieve diversity in the news business would be complete without the story of Robert C. Maynard, the first African American editor and owner of a major daily newspaper in the United States, the Oakland (Calif.) Tribune.

Maynard was a trailblazing journalist who co-founded what is now the Maynard Institute for Journalism Education with his wife, Nancy Hicks Maynard, and together they and their team led efforts to desegregate newsrooms and educate students of color to pursue careers in journalism.

African Americans were just 2 percent of newspaper employees in 1978, few in decision-making roles, and two-thirds of the nation’s papers had no employees of color, according to a survey by the American Society of Newspaper Editors.

The Maynards wanted to eliminate from the lexicon the excuse “can’t find anybody qualified.” They had a chance to implement the practices they preached when the Gannett Co. sold the money-losing Oakland Tribune to the couple in 1983. Bob Maynard had been editor since 1979.

Then, as now, Oakland was multicultural. Today, the city is 32.3 percent white alone; 15.9 percent Asian alone, 28.6 percent Hispanic alone, and 21.8 percent Black or African American, according to U.S. Census population estimates for 2023. The estimates also include smaller percentages of people of two or more races, American Indians, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders.

Into this mix arrived William Gee Wong, an Oakland native and Chinese American who wrote for the Wall Street Journal as well as the San Francisco Chronicle, San Francisco Examiner and Asian American periodicals. In his recent memoir, “Sons of Chinatown: A Memoir Rooted in China and America,” excerpted below, Wong describes what it was like to be the first Asian American columnist at the Maynards’ Oakland Tribune. He joined the paper from the Wall Street Journal in 1979. He was the Tribune’s business editor and reader’s representative before becoming a columnist in 1988.

The journalistic efforts of Wong and others weren’t able to save the Tribune, which the Maynards sold in 1992, but during their time there, Tribune columnist Tammerlin Drummond wrote, “It was a gutsy, scrappy newspaper that reflected its community,” though “The Tribune always operated on a shoestring and the goodwill of its devoted employees.” In 1990, the newspaper won a Pulitzer Prize for photography for coverage of the Loma Prieta earthquake.

This video was made as part of the Oakland History Murals project by Bay Area history teacher Mike Burton. It was provided by the Maynard Institute when Robert Maynard received the Freedom Forum’s Free Spirit Award posthumously in 1994. (Credit: YouTube)

By William Gee Wong

Robert C. Maynard was an affable yet arrogant man, brilliant, charismatic, effusive, and full of himself, yet charming. He dressed stylishly, in well-starched English-made dress shirts, colorful silk ties, and well-tailored dark suits. He spoke precisely in a deep, low cadence, punctuated by an occasional grin or sly smile.

He got your attention. His weekly column was elegantly written, often with an uplifting moral message. He gained national recognition as a frequent guest commentator on ABC-TV’s “This Week with David Brinkley” show. He was quite a contrast to my more introverted, much less fashionable, and decidedly uncharismatic persona.

Sometimes, being in his presence could be intimidating and overwhelming. I was mildly shocked the first time we had lunch together in Chinatown. He ordered in Mandarin, which I didn’t speak. I hid my personal shame. Here I was, the Chinatown Chinese guy, who couldn’t do what this outgoing, smart Black guy could, right there in my own Chinatown! Nonetheless, we had convivial conversations over delicious food, and I found him relaxed and personable.

As his status and power grew — from mere editor-in-chief to publisher to owner — our relationship became more distant, but still cordial. . . .

The paper’s financial troubles were rooted in the reluctance of traditional advertisers (big retailers, car companies) to support a newspaper that had a thin middle-class and upper-middle-class readership who wasn’t largely white. Its suburban competitors had that financially more desirable market now.

After the initial high of joining the Gannett family, the excitement of Maynard’s appointment, and the splashy East Bay Today debut, many of us worker bees became increasingly stressed as the paper was dangerously teetering.

Rumors swirled about the paper’s imminent demise. The union representing newsroom employees made concessions on wages and working conditions to help keep the paper afloat.

More than once, I sought newspaper jobs elsewhere. Colleagues did the same or simply quit. I went to Portland, Oregon, to interview for an editing job at the Oregonian. Nothing came of that. The San Francisco Examiner wanted me to be its business editor for a small kick up in pay and the promise of a parking space (a precious commodity!), but I decided to stay at the Tribune, for that position wasn’t what I was looking for. My administrative-personnel assistant managing editorship was hardly a personal morale boost.

I did the job, but I wasn’t the happiest camper.

Faculty, staff and reporter-graduates gather after closing ceremonies in 1976 of the Summer Program for Minority Journalists, which had conducted its first training session at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism. The program then was run by the Institute for Journalism Education, later renamed the Maynard Institute. Robert C. Maynard is at bottom, left, Leroy F. Aarons, who worked with Maynard at the Oakland Tribune as executive editor, is second from right. (Credit: photo by Nikki Arai; courtesy of Frank Sotomayor.)

Then that mythical thought-bubble light bulb illuminated: Why not write a column full-time?

Why not indeed? I approached Maynard and Leroy Aarons [the new executive editor], and they agreed, with Aarons expressing reservations. When I told them that I wanted to include Chinese American and Asian American themes, Aarons questioned its sustainability.

My new column-writing gig didn’t immediately replace my administrative duties. My early columns appeared once every other week on the editorial pages, with my name and photo prominently displayed. My first such column discussed the status of Asian Americans and why President Jimmy Carter had designated nine years earlier an Asian Pacific American Heritage Week. Two weeks later, my second column, headlined “The roots of Asian American crime,” focused on a national conference in Oakland of public officials addressing a growing crime problem in Asian American communities.

Those two columns were a good start to offer my thoughts on topics that were ignored by newspapers like the Tribune and that I was well positioned to address. They began to fulfill a long-term wish of mine to write about “my community” in a mainstream newspaper that had a readership much wider than Chinatown, Chinese America, and Asian America.

A few months later, by mid-September of 1988, my column went weekly. A month later, I made the full transition, with a new title, associate editor, lofty but largely meaningless. More important, my column began running three days a week. I was back to what had energized me about journalism — writing and telling stories.

As a columnist, one has a luxury that reporters don’t. You can express an opinion or a point of view. I saw this column as a perfect opportunity to deepen my racial-ethnic identity search and to highlight topics that were largely hidden from wide public consumption. At the same time, I knew not to write exclusively along racial-ethnic lines. That would be much too limiting and would pigeonhole me. Yet even when yellow ethnic themes formed only a fourth to a third of all my columns, I know that many folks thought of me as an “Asian American” columnist. That label has at least two interpretations: One is descriptive, and the other is limiting.

My mission was essentially twofold: Introduce Tribune readers to topics they had rarely read about but that were intricately interwoven with Oakland life and journalistically explore topics close to my soul. In my eight years of writing columns, I wrote about Oakland’s Chinatown as well as Chinese American and Asian American matters of all sorts.

Most of my Tribune columns, however, weren’t devoted to those specialties. The subjects I addressed were eclectic, from local people and politics to regional, state, national, and international politics and culture, from the personal to perplexing social and cultural issues. For example, I opposed President George H. W. Bush’s Gulf War. I favored sensible gun regulations. I wrote about parenting joys and challenges. I took on arts and cultural matters that intersected with race and class. I highlighted our society’s growing multiculturalism. Sometimes, I engaged a playful, satirical, humorous voice.

A favorite column was published on January 30, 1989. A white Canadian psychologist had made a racially charged presentation at a San Francisco scientists’ convention. His theory was that “Orientals” were superior to white or Black people in intelligence and social organization. His underlying message was that Black people were intellectually inferior. “Orientals” have bigger brains in cranial capacity and brain weight, he said. “That must be why I can’t lose any weight,” I wrote.

Before widespread use of the Internet and such social media platforms as Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, TikTok, and Instagram, being a newspaper columnist raised one’s public profile. Shortly after my columns started running regularly, Nancy Hicks Maynard congratulated me on “beginning to find your voice,” a high compliment from the boss’s wife. A local Asian American activist power couple wrote to Maynard, thanking him for giving me a column. They liked that I wrote widely, not just about Asian American issues.

General reader response was, as expected, good and bad. How readers communicated with a columnist was decidedly old-fashioned — calling on a landline phone or writing a letter on paper and mailing it in with a stamp.

One reader hand-wrote me letters telling me that he hated my stuff, which led me to wonder: Why does this guy continue reading me when he doesn’t like what I have to say? After a column on Oakland political redistricting in which I highlighted the need to consolidate Asian American voters, one reader, “A concerned Black citizen,” wrote, “If Chinese-Asians practiced birth control like everybody else there wouldn’t be — so much population growth and burden on our City. And if the Chinese stayed off the boats and in China where they belong, they would not be here driving up my taxes and trying to take something that belongs to somebody else.”

William Gee Wong published a podcast based on “Sons of Chinatown” in August. (Credit: YouTube)

Following a column about the Los Angeles mayoral race, in which Richard Riordan, a white man, had defeated Michael Woo, a Chinese American, a reader, signing his letter, “East Side White Pride, Oakland CA 94607,” wrote, “You are an Asian racist. You are a hatemonger. You spew all of your poison sewage against whites eternally on the behalf of black activists.”

Among Tribune colleagues, the response to my columns was more muted, nuanced, and indirect.

Some told me directly that they liked what I was doing. One qualified his praise by saying that, in general, columnists don’t hit the mark every time, but he believed that I did so often enough.

One popular reporter, a white guy, liked to josh me about what he thought was my naïveté about a possible harmonious multicultural future that I sometimes conveyed in my columns about California’s and America’s browner demographic future. His edgy but good-natured skepticism was typical of the mind-set of others, I’m sure.

The oddest inside response came from a female reporter and desk editor, who had once worked under my business-editor command and, later, on the city desk. She was a quick, reliable, if opinionated colleague, one I wasn’t particularly close to. After my column had been running a while, she came into my little office, told me that she

liked what I had just written, and promptly walked out.

Later, I heard the gossipy backstory on why she did that. Out of my earshot, she had earlier scoffed at my writing, so she wanted to show those she had complained to that she could, indeed, say something nice about me to my face.

My racially themed columns apparently upset at least one Tribune employee who worked in the basement where the papers were printed. A tall, muscular white man approached me one day, not in a threatening manner, but more in exasperation about what he believed was my antiwhite attitude. We chatted briefly without anger or resolution. At least he didn’t choose to bop me.

Others also didn’t like what I was writing. I regularly parked my car in a lot across from our newsroom. One day, I found nails hammered into the two back tires of my car. That wasn’t accidental.

* * *

From Sons of Chinatown: A Memoir Rooted in China and America by William Gee Wong. Used by permission of Temple University Press. © 2024 by Temple University. All Rights Reserved.

Sons of Chinatown can be purchased from Temple University Press here.

Postscript:

Under the new owners, the Alameda Newspaper Group, Wong was let go in 1996 – an act that triggered loud protests from readers and Asian Americans in the Bay Area. In a previous book, “Yellow Journalist: Dispatches from Asian America,” Wong voiced suspicions that the new owners and their “conservative white editors … did not like my politics and … my writing so often about Asian American issues.” However, the Alameda County Superior Court dismissed a lawsuit by Wong alleging age and racial discrimination and breach of contract.

The newspaper group said the termination was for economic reasons.

- Leonard Chan, Asian American Curriculum Project: An Interview With Journalist and Author William Gee Wong (April 30)

- Bill Drummond, University of California at Berkeley: Celebrating Early Diversity Initiatives at Berkeley Journalism: An Essay by Professor Bill Drummond (Feb. 25, 2022)

- Bruce Lambert, New York Times: Robert C. Maynard, 56, Publisher Who Helped Minority Journalists (Aug. 19, 1993)

- Linda Liu, San Francisco Chronicle: Oakland Chinatown-native journalist pens ‘an illegal immigration success story’ (Aug. 14)

- Kimberley Mangun, Black Past: Robert C. Maynard (1937-1993) (2008)

- Eric Newton, Knight Foundation: Bob Maynard, media diversity, and a story without an ending (Dec. 23, 2013)

Ta-Nehisi Coates joins “CBS Mornings” Sept. 30 to talk about his new book, “The Message,” and about the banning of his work in South Carolina. (Credit: YouTube)

CBS Faults ‘Mornings’ Interview of Ta-Nehisi Coates

“A contentious interview last week on CBS Mornings did not meet the network’s editorial standards,” Alex Weprin reported Monday for The Hollywood Reporter.

“That was a message shared by CBS News brass to staff in an editorial meeting Monday.

“Last week’s interview saw CBS Mornings co-host Tony Dokoupil speak with author Ta-Nehisi Coates about his new book The Message, which passionately argues that Israel’s treatment of Palestinians is immoral and should be condemned.

“The interview was contentious, but civil, with Dokoupil asking pointed questions of Coates like ‘Why leave out that Israel is surrounded by countries that want to eliminate it?’ and comments like ‘I have to say, when I read the book, I imagine if I took your name out of it, took away the awards, the acclaim… the content of that section would not be out of place in the backpack of an extremist.’

“Not surprisingly given the high emotional stakes of anything that involves Israel and Palestine, the interview garnered a strong reaction online, and within CBS News, with some arguing that the tough questions were justified, and others arguing that Dokoupil’s personal views were a factor.

“Ultimately, the tone of Dokoupil’s interview was what warranted a response from CBS News executives Wendy McMahon and Adrienne Roark, who heads newsgathering. The executives told CBS staff that the interview did not meet the network’s editorial standards. . . .”

“Coates himself was asked about the CBS interview by Mehdi Hasan, telling him ‘I was a little surprised, and then I realized what was going on, I was in a fight,’ he said.

“ ‘So it was right there, you know, as a pop quiz, but I had studied,’ he continued.”

-

- Perry Bacon Jr., Washington Post: Why you should read Ta-Nehisi Coates’s new book

To subscribe at no cost, please send an email to journal-isms+subscribe@groups.io and say who you are.

Facebook users: “Like” “Richard Prince’s Journal-isms” on Facebook.

Follow Richard Prince on Twitter @princeeditor

Richard Prince’s Journal-isms originates from Washington. It began in print before most of us knew what the internet was, and it would like to be referred to as a “column.” Any views expressed in the column are those of the person or organization quoted and not those of any other entity. Send tips, comments and concerns to Richard Prince at journal-isms+owner@

View previous columns (after Feb. 13, 2016).

View previous columns (before Feb. 13, 2016)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2018 (Jan. 4, 2019)

- Book Notes: Is Taking a Knee Really All That? (Dec. 20, 2018)

- Book Notes: Challenging ’45’ and Proudly Telling the Story (Dec. 18, 2018)

- Book Notes: Get Down With the Legends! (Dec. 11, 2018)

- Journalist Richard Prince w/Joe Madison (Sirius XM, April 18, 2018) (podcast)

- Richard Prince (journalist) (Wikipedia entry)

- February 2018 Podcast: Richard “Dick” Prince on the need for newsroom diversity (Gabriel Greschler, Student Press Law Center, Feb. 26, 2018)

- An advocate for diversity in the media is still pressing for representation, (Courtland Milloy, Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2017)

- Morgan Global Journalism Review: Journal-isms Journeys On (Aug. 31, 2017)

- Journal-isms’ Richard Prince Wants Your Ideas (FishbowlDC, Feb. 26, 2016)

-

Richard Prince with Charlayne Hunter-Gault, “PBS NewsHour,” “What stagnant diversity means for America’s newsrooms” (Dec. 15, 2015)

- Book Notes: Journalists Follow Their Passions

- Book Notes: Journalists Who Rocked Their World

- Book Notes: Hands Up! Read This!

- Book Notes: New Cosby Bio Looks Like a Best-Seller

- Journo-diversity advocate turns attention to Ezra Klein project (Erik Wemple, Washington Post, March 5, 2014)