Pan-Africanist Has Message for Journalists

Journal-isms Roundtable photos by Sharon Farmer/sfphotoworks

[btnsx id=”5768″]

Donations are tax-deductible.

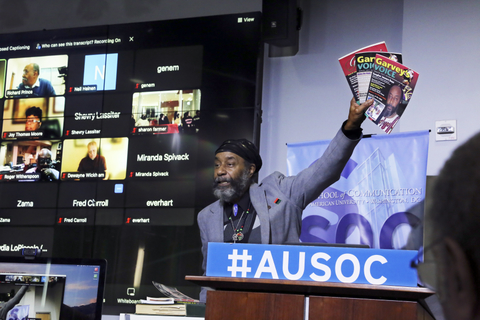

Ten visitors joined American University students on campus, with 25 more participants on Zoom. Eighty had watched on Facebook as of March 11, and 45 more on YouTube. (Credit: American University/YouTube.)

Pan-Africanist Has Message for Journalists

By Isaiah J. Poole

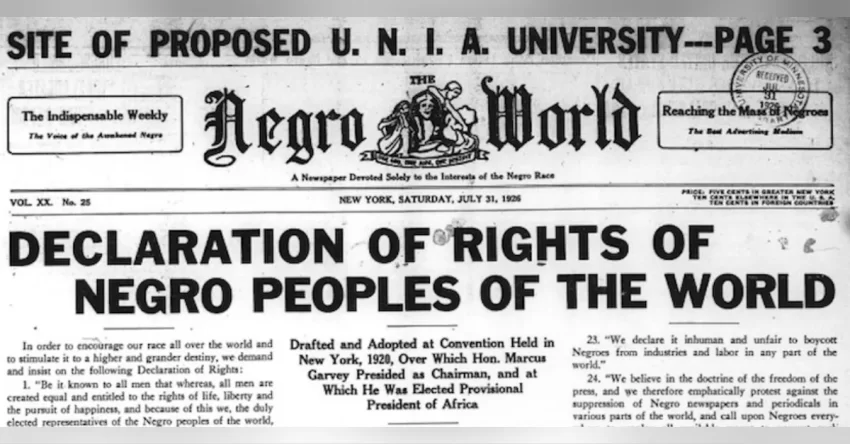

While he is perhaps best known for his controversial championing of Pan-Africanism, the early 20th century back-to-Africa movement and the creation of the red, black and green Black liberation flag, Marcus Garvey also left behind a journalistic legacy.

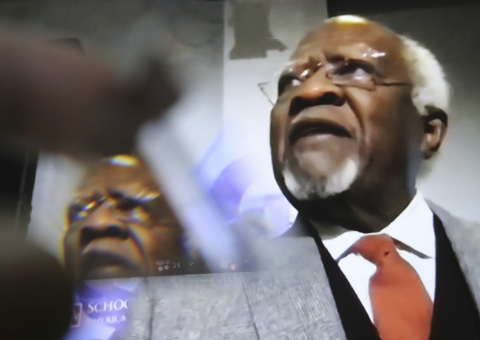

It is one that sets a standard for contextualizing the struggles and vitality of Black people in America and globally, his surviving son, Dr. Julius Garvey, told the Journal-isms Roundtable on Feb. 6.

The message to Black journalists today, said Dr. Garvey, a cardiothoracic surgeon who turns 90 in August, is that “you should not sell your soul, because I think what has happened to a lot of journalists in this country is that they’re more purveyors of propaganda than actually transmitters of truth.”

Instead, “try to be honest, because honest journalism will transform the world in the right direction.”

The Negro World newspaper, which his father founded and his mother, Amy Jacques Garvey, helped run, came on the scene in 1918. The prevailing journalism “was basically a propagandist journalism that talked only about what was happening in America, as if America was the center of the world,” Dr. Garvey said.

“But my father came from a background of travel. . . .”

The Roundtable was the first as a hybrid, conducted simultaneously in-person and online, and its first in-person occasion since the COVID pandemic took hold in 2020. It was the inaugural event of Journal-isms’ year-old partnership with American University’s School of Communication, led by Dean Sam Fulwood III.

Ten visitors joined American University students on campus, with 25 more participants on Zoom. Eighty had watched on Facebook as of March 11, and 45 more on YouTube. You can watch the embedded video above or here.

“Journalism actually was the expression of Garveyism,” Garvey (pictured) said. His newspaper “introduced internationalism to America, especially to Black America.” Through a mix of news, commentary and literature, the Negro World represented “something novel in terms of Africans in America looking outside of America and understanding that the problems that they faced in America were global problems.”

“Journalism actually was the expression of Garveyism,” Garvey (pictured) said. His newspaper “introduced internationalism to America, especially to Black America.” Through a mix of news, commentary and literature, the Negro World represented “something novel in terms of Africans in America looking outside of America and understanding that the problems that they faced in America were global problems.”

The significance and impact of Garvey and the Negro World were underscored by Paulina Laura Alberto, professor of African and African American studies and history at Harvard University and editor of “Voices of the Race: Black Newspapers in Latin America, 1870-1960,” and by Senghor Baye, a longtime leader of the current iteration of Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA).

The Negro World was launched as a weekly by Garvey in 1918 under the auspices of UNIA and published through 1933. The paper was one of the more durable enterprises in what became a sprawling collection of business interests that Garvey built, from retail stores to The Black Star Line, envisioned as a fleet of ships that would serve as a direct connection between Black Americans and Africa.

Various historical accounts estimate that the weekly circulation of the newspaper at its peak was as high as 500,000. “The artistic contribution of Garvey and the Negro World may have been greater had not the work of the UNIA been hindered from 1923 to 1927 by Garvey’s trial, imprisonment, and deportation” on mail fraud charges associated with stock sales for the Black Star Line, Baye said.

But even in the midst of the federal government actively looking for ways to bring down Garvey and his movement, “no other publication of the time, neither the Opportunity [a National Urban League scholarly journal published from 1923 to 1949], nor The Crisis [the organ of the NAACP that was launched under W.E.B. Du Bois in 1910], nor anything else came close to the Negro World with a sheer magnitude of its literary output,” Baye said.

“As many as dozens of poems, short stories, book reviews, articles of literary criticism, and the like might be found in a single issue of the paper. The authors might range from major literary and intellectual figures like William H. Ferris, Eric Walrond, Zora Neale Hurston, Arthur Schomburg, J. A. Rogers, Alain Locke, Hubert Harrison and John Edward Bruce to unknown, aspiring writers from Africa, Afro-America, Canada, Central America, the Caribbean, and any place where a UNIA was established and where the newspaper was read,” Baye continued.

In his talk, Julius Garvey said the newspaper was key in expanding the membership of the UNIA to as high as 6 million. But he emphasized the breadth of its reach. The paper translated its editorials into Spanish and French and distributed them throughout Central and South America, and Brazilian supporters of UNIA translated the paper into Portuguese. Black sailors took copies of the Negro World to Africa.

“One interesting anecdote, which is in Jomo Kenyatta’s book “Facing Mount Kenya,” is that when somebody brought the edition of the Negro World newspaper to Kenya, the people would gather around and they would read the editorial page by Marcus Garvey over and over until it was memorized by a group that ran off into the different villages to spread the word.”

In its efforts to encourage Black pride, the Negro World declined advertising for hair straighteners and skin-lightening creams. “It was the backbone of the Black consciousness movement,” Julius Garvey said.

Throughout Latin America, “the Negro World provided enormous support, information, and inspiration” to the African diaspora resisting racism and colonialism, Alberto said. Articles from the Negro World, as well as other Black American newspapers, were frequently translated and reprinted in their counterparts in Latin America, contributing to vigorous debates about Garvey’s ideas.

When the Negro World went defunct, Baye said, other newspapers rose to keep the topics alive.

In addition to the Negro World, Marcus Garvey briefly published a daily in New York City, The Daily Negro Times, in 1922, and a literary magazine, The Black Man, “a monthly journal of Negro thought and opinion,” which circulated from the early 1930s through 1939.

During a question-and-answer period, Julius Garvey was dismissive of documentaries about his father’s legacy, including “Marcus Garvey: Look for Me in the Whirlwind,” a PBS documentary from award-winning filmmaker Stanley Nelson that aired in 2001, which he called “scandalous. I had him down in Jamaica; we tore him apart.

“There are several [films] out there, but not necessarily approved by me, not necessarily genuine, because, you know, people are still trying to distort the message. So a real good story about my father in terms of a documentary or a movie has not been out there yet as far as I’m concerned,” Garvey said.

Baye said that Nelson’s documentary on the Black press, “Soldiers Without Swords,” did not mention the Negro World.

Nelson, reached for comment, said that both Julius Garvey and his brother, the late Marcus Garvey Jr., are both briefly featured in “Look for Me in the Whirlwind.”

In a brief interview, Nelson said he stands by the documentary and specifically rejected Garvey’s characterization of the Jamaica event, which took place the year the documentary first aired. “A lot of different opinions” about Garvey’s legacy were expressed at the event, he recalled, and he does not recall being particularly under attack. He also defended this decision to include only a brief mention of the Negro World in “Soldiers Without Swords.” “The Negro World was a very different newspaper because it was an arm of the UNIA,” Nelson said, compared with the other papers featured.

The Roundtable also heard from the Rev. Alexander Gee, a Madison, Wis., nonprofit leader and pastor who is working to establish a Center for Black Excellence and Culture there. “Madison doesn’t feel like home for the Black community,” Gee said, adding that he envisions the center as a place that uses culture and identity to foster a holistic sense of wellness, “the type of wellness that the Black community had way before integration, when there was more shared Black legacy and excitement and excellence.”

Gee said he has $23 million of the $36 million he and his collaborators are raising to get the center built and operating. The facility will provide “an opportunity to have the space to create and to come together and think and plan for ourselves in a space that we own, with faculty and doctors and professionals and children and moms, and formerly incarcerated folks. It makes room for mentoring and leading and teaching and healing and empowering and networking and incubating. What we found is that when we can have space to be ourselves, we can heal ourselves, and we don’t need all the social services that are put on us now.”

The Roundtable also toasted Joy Thomas Moore, mother of new Maryland Gov. Wes Moore — only the third elected Black governor in the nation’s history and the wife of the late journalist William Westley Moore Jr., best known as Wes Moore, whose career included stints at both WMAL radio and WRC-TV in Washington.

“After Wes passed, it was the journalists, the journalists in Washington who really, really rallied around us,” the new governor’s mother, an American University journalism graduate, told the group. She added that her son wants “to make sure that everyone has a voice and a seat at the table.” Roger Glass, a past president of the Washington Association of Black Journalists, recalled when his group created the Wes Moore Scholarship Fund in the 1980s.

Differing views on the role of Black journalists surfaced when an African American student asked, “How do I navigate reporting the truth in a predominantly white field without compromising my Blackness? . . .”

Michel Martin, just this week named a co-host of NPR’s “Morning Edition,” responded that “there is no one Black truth. . . . you are here to report stories to the best of your ability. You are here to tell the truth. You are here to have integrity. First, you need to master your craft. . . . Master yourself. Have emotional discipline, have intellectual discipline. Strive for excellence, and the truth will come.”

Jesse W. Lewis Jr., former Washington Post reporter, editorial writer and foreign correspondent, agreed: “There is no such thing as an orthodox Black view.”

However, DeWayne Wickham, founding dean of the Morgan State University School of Global Journalism & Communication and a founder and past president of the National Association of Black Journalists, countered, “there is a spine of consciousness that runs through the Black community. . . .

“There is in the Black press, and I think you will find among most Black journalists, either publicly acknowledged or not, that there is a spine of consciousness that has to do with our support around rights to equal opportunity in this country and our rights to a claim of fairness and justice as we demanded, and our assertion [that] the 13th or even 15th amendment to the Constitution ought to be treated as a bible of sort for Black folks.

“So when it comes to those issues of rights and citizenship, right to vote and right to own property and rights to be treated fairly in courts and in law, I don’t think there’s a great disagreement among Black folks. . . .”

- New York Carib News: Rep. Yvette Clarke Calls for Garvey Exonerated in Congress

Nominate a J-Educator Who Promotes Diversity

Beginning in 1990, the Association of Opinion Journalists, now part of the News Leaders Association, annually granted a Barry Bingham Sr. Fellowship — actually an award — “in recognition of an educator’s outstanding efforts to encourage minority students in the field of journalism.”

Since 2000, the recipient has been awarded an honorarium of $1,000 to be used to “further work in progress or begin a new project.”

Past winners include James Hawkins, Florida A&M University (1990); Larry Kaggwa, Howard University (1992); Ben Holman, University of Maryland (1996); Linda Jones, Roosevelt University, Chicago (1998); Ramon Chavez, University of Colorado, Boulder (1999); Erna Smith, San Francisco State (2000); Joseph Selden, Penn State University (2001); Cheryl Smith, Paul Quinn College (2002); Rose Richard, Marquette University (2003).

Also, Leara D. Rhodes, University of Georgia (2004); Denny McAuliffe, University of Montana (2005); Pearl Stewart, Black College Wire (2006); Valerie White, Florida A&M University (2007); Phillip Dixon, Howard University (2008); Bruce DePyssler, North Carolina Central University (2009); Sree Sreenivasan, Columbia University (2010); Yvonne Latty, New York University (2011); Michelle Johnson, Boston University (2012); Vanessa Shelton, University of Iowa (2013); William Drummond, University of California at Berkeley (2014); Julian Rodriguez of the University of Texas at Arlington (2015); David G. Armstrong, Georgia State University (2016); Gerald Jordan, University of Arkansas (2017), Bill Celis, University of Southern California (2018); Laura Castañeda, University of Southern California (2019); Mei-Ling Hopgood, Northwestern University (2020); Wayne Dawkins, Morgan State University (2021); and Marquita Smith of the University of Mississippi (2022).

Nominations may be emailed to Richard Prince, Opinion Journalism Committee, richardprince (at) hotmail.com. The deadline is April 7. Please use that address only for NLA matters.

‘[btnsx id=”5768″]

To subscribe at no cost, please send an email to journal-isms+subscribe@groups.io and say who you are.

Facebook users: “Like” “Richard Prince’s Journal-isms” on Facebook.

Follow Richard Prince on Twitter @princeeditor

Richard Prince’s Journal-isms originates from Washington. It began in print before most of us knew what the internet was, and it would like to be referred to as a “column.” Any views expressed in the column are those of the person or organization quoted and not those of any other entity. Send tips, comments and concerns to Richard Prince at journal-isms+owner@

View previous columns (after Feb. 13, 2016).

View previous columns (before Feb. 13, 2016)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2018 (Jan. 4, 2019)

- Book Notes: Is Taking a Knee Really All That? (Dec. 20, 2018)

- Book Notes: Challenging ’45’ and Proudly Telling the Story (Dec. 18, 2018)

- Book Notes: Get Down With the Legends! (Dec. 11, 2018)

- Journalist Richard Prince w/Joe Madison (Sirius XM, April 18, 2018) (podcast)

- Richard Prince (journalist) (Wikipedia entry)

- February 2018 Podcast: Richard “Dick” Prince on the need for newsroom diversity (Gabriel Greschler, Student Press Law Center, Feb. 26, 2018)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2017 — Where Will They Take Us in the Year Ahead?

- Book Notes: Best Sellers, Uncovered Treasures, Overlooked History (Dec. 19, 2017)

- An advocate for diversity in the media is still pressing for representation, (Courtland Milloy, Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2017)

- Morgan Global Journalism Review: Journal-isms Journeys On (Aug. 31, 2017)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2016

- Book Notes: 16 Writers Dish About ‘Chelle,’ the First Lady

- Book Notes: From Coretta to Barack, and in Search of the Godfather

- Journal-isms’ Richard Prince Wants Your Ideas (FishbowlDC, Feb. 26, 2016)

- “JOURNAL-ISMS” IS LATEST TO BEAR BRUNT OF INDUSTRY’S ECONOMIC WOES (Feb. 19, 2016)

- Richard Prince with Charlayne Hunter-Gault, “PBS NewsHour,” “What stagnant diversity means for America’s newsrooms” (Dec. 15, 2015)

- Book Notes: Journalists Follow Their Passions

- Book Notes: Journalists Who Rocked Their World

- Book Notes: Hands Up! Read This!

- Book Notes: New Cosby Bio Looks Like a Best-Seller

- Journo-diversity advocate turns attention to Ezra Klein project (Erik Wemple, Washington Post, March 5, 2014)

73 comments