Loss to Reagan Was to Some a Bad Dream

Statement by Former President Obama and Michelle Obama

Clyburn Lauds Carter on Judgeships, Showing ‘How to Lose’

From Dec. 27: On Richard Parsons: What Race Has to Do With It

Sportscaster Greg Gumbel Dies of Cancer at 78

[btnsx id=”5768″]

Donations are tax-deductible.

Adapted from column originally published Feb. 19, 2023

Loss to Reagan Was to Some a Bad Dream

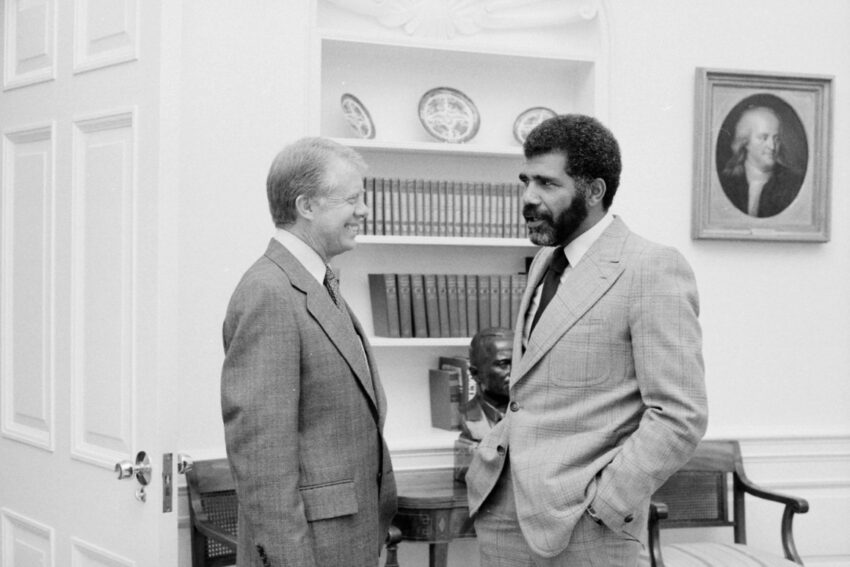

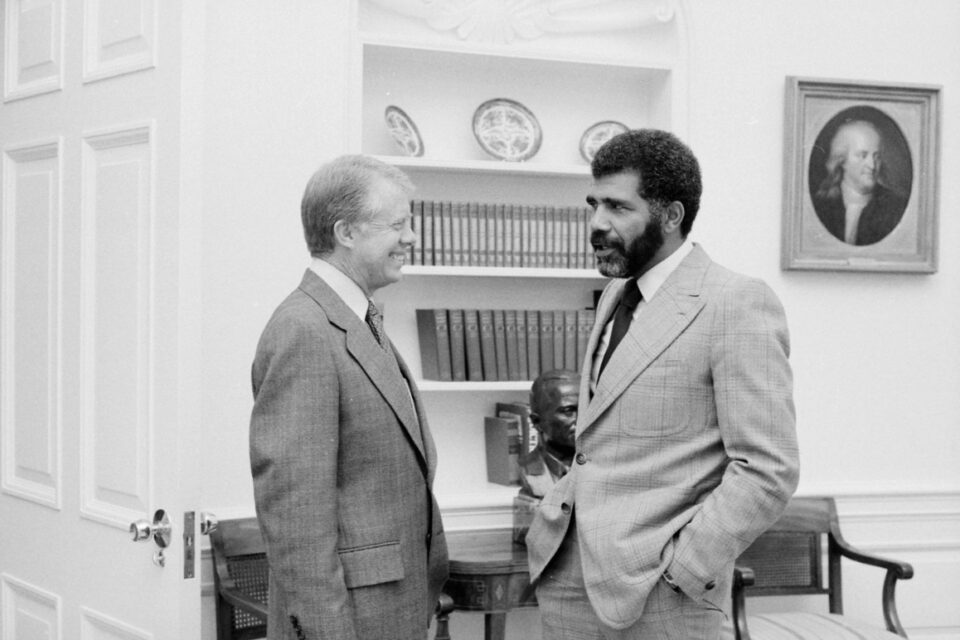

When Jimmy Carter sat down with 29 Black media representatives at the White House on Feb. 16, 1978, he admitted that at his news conferences, the only Black reporter he remembered by name was Ed Bradley of CBS.

“At press conferences, I don’t know many of the names of the reporters who serve on the White House press pool,” Carter said. “I know we had a reception for them Christmas; we had, I think, 1,400 people who came. There are hundreds of them. And I try to do the best I can to spread the questions around. But one Black reporter that I call on every now and then is Ed Bradley with CBS. And I try to spread my questions around.”

“We’ll give you the names of our Black-owned newspapers,” came one response. Ed Bradley is with CBS.”

“Yes, I know,” Carter replied.

“We are desirous, however, [that] our Black-oriented publications have an opportunity to ask our President a question,” came the response.

“I think that’s a good idea,” Carter said.

The National Association of Black Journalists, which had 12 board members at the meeting, was not yet three years old. The session with Carter and his Cabinet “legitimized the organization to media executives,” NABJ would later say. The National Association of Black Owned Broadcasters and the National Newspaper Publishers Association, which advocates for Black-press publishers, were also represented.

Carter died on Sunday, more than a year after entering hospice care, at his home in the small town of Plains, Ga., the Associated Press reported Dec. 29, citing the Carter Center. Plains was where Carter and his wife, Rosalynn, who died at 96 in November 2023, spent most of their lives.

He was the oldest living former president.

Carter beat Republican incumbent Gerald R. Ford in the 1976 presidential election, thanks to the Black vote. “The Washington Post reported that as much as 96 percent of the national black population voted for Carter, and a study conducted by the Joint Center for Political Studies in Washington, D.C. backed those findings,” recounted Marva L. Washington, who wrote a thesis on the 1976 campaign for California State University – Northridge.

But the Black press was not always in Carter’s corner. Robert S. Allison, editor of the Los Angeles Herald-Dispatch, asserted during the campaign that Carter was created and being “sold” to Blacks by the white media, Washington wrote.

During that contest, NABJ was angry that it had been snubbed. The organization invited both Ford and Carter to its first annual convention, held at Texas Southern University in Houston, but both declined, citing scheduling conflicts. However, at the last minute, Carter invited a small group of Black journalists to meet privately with him for 45 minutes in Chevy Chase, Md., Wayne Dawkins wrote in 1993’s “Black Journalists: The NABJ Story.”

“For Carter to schedule such a meeting on the same day as the first significant black journalist conference in another city is a typical divisive tactic that caused some of the cataclysms we are witnessing in South Africa,” responded NABJ, then led by outspoken Chicago columnist Vernon Jarrett (pictured).

“For Carter to schedule such a meeting on the same day as the first significant black journalist conference in another city is a typical divisive tactic that caused some of the cataclysms we are witnessing in South Africa,” responded NABJ, then led by outspoken Chicago columnist Vernon Jarrett (pictured).

Still, some in Black media were impressed with Carter, such as John H. Johnson, publisher of Ebony and Jet magazines. In his 1989 autobiography, “Succeeding Against the Odds,” written with Lerone Bennett Jr., Johnson writes that he convened, at Carter’s request, an early-morning editorial board meeting.

“Carter walked in cold on that morning and captivated us. The first thing he said to me was, ‘Mr. Johnson, I’m glad to meet you. We’re both Morehouse Men.’ He was technically correct, for both of us had received honorary degrees from the predominantly Black college that produced Martin Luther King, Jr.

“More importantly, he was politically correct in stressing his identification with a tradition and a dream. I knew then that the peanut farmer from Plains, Georgia, was going far, and I was not surprised when he walked away with all the marbles.”

When Carter lost re-election in 1980 to Ronald Reagan, there was no disguising Black America’s sense of loss.

“Along towards midnight of November 4,” wrote the venerated Black journalist Ethel Payne (pictured), “the emotional reaction among blacks across the country to the landslide victory of Ronald Reagan came close to a massive breakdown,” she said, according to James McGrath Morris in his 2015 biography, “Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne, the First Lady of the Black Press.”

“Along towards midnight of November 4,” wrote the venerated Black journalist Ethel Payne (pictured), “the emotional reaction among blacks across the country to the landslide victory of Ronald Reagan came close to a massive breakdown,” she said, according to James McGrath Morris in his 2015 biography, “Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne, the First Lady of the Black Press.”

“In her own case, the election caused her to wake up in the middle of the night from a dream in which the Ku Klux Klan, the Moral Majority, and the Christian Voice — the latter two being conservative groups that triumphed in 1980 — were conducting a purge of undesirable blacks.”

While Carter made news in the mainstream press at that 1978 meeting with comments about conflict between Ethiopia and Somalia, then in the news, the African American journalists around the table also asked about Black progress in the American media.

“Our administration over this past year has been very concerned about the difficulty of Black citizens and other minority groups in trying to acquire ownership of the electronic media,” Carter said in response to a question about the continuing deficit in ownership by people of color.

“And on behalf of the minority citizens of our country, we have now filed a petition directly with the Federal Communications Commission, as you know, and I have sent a message to Congress – – and [deputy press secretary] Walt Wurfel or somebody can get you a copy of it — expressing to Congress the need to ensure that in the future black citizens and black citizens’ groups can acquire ownership and control of the electronic media, both television and radio.”

And in a pledge echoed in 2023 in an executive order from President Biden, Carter said, “we have passed our goal of having $100 million in Federal money deposited in minority-owned banks, and we will meet our goal of more than 10 percent of the local public works projects being devoted or assigned to minority businesses for completion. I’ve instructed all executive agencies in the Federal Government to double in this and the next fiscal year the amount of purchases of equipment and supplies from black or minority-owned businesses.”

The National Newspaper Publishers Association and the National Association of Hispanic Publications, along with others, have long pressed for advertising spending by government agencies in media owned by people of color.

In fact, in an exchange that highlighted the difference between journalists and publishers, Calvin Rolark, publisher of the Washington Informer, said to Carter, “Mr. President, why don’t you buy an ad in my newspapers?”

“Carter was stunned by the question,” Dawkins reported in “Black Journalists: The NABJ Story.”

” ‘Well,’ the president said, ‘that’s not my job.’ “

“The president saw us (NABJ and NNPA people) as all the same. I never got the impression that the White House understood the distinction or they wouldn’t have invited us together,” ” Allison Davis, an NABJ co-founder and then its vice president, told Dawkins.

Carter also met with Black journalists in January 1979, when, W. Dale Nelson wrote for the Associated Press, Carter declared that “Persons nominated to be federal judges will be asked whether they belong to clubs that exclude blacks or women if the Senate Judiciary Committee adopts a questionnaire it is considering,” according to Nelson’s story.

While some might consider covering the White House a dream assignment, it wasn’t seen that way by every journalist.

In 2022, Austin Long-Scott (pictured), who reported from the Carter White House, described it this way for Journal-isms:

In 2022, Austin Long-Scott (pictured), who reported from the Carter White House, described it this way for Journal-isms:

“It was supposed to be a fantastic assignment, great for my professional career, one of the high honors of journalism. I would be not just a White House Correspondent, but the second African American in that job at the increasingly prestigious Washington Post that had just exposed the Watergate scandal which toppled President Richard Nixon.

“And I would be covering peanut farmer and former Georgia Gov. Jimmy Carter, the Democrat who ended eight years of GOP Presidents in 1976. But it didn’t work out the way it was supposed to. And not just because I limped up the icy White House driveway for the first few weeks on crutches, having broken my ankle during a backyard ice hockey game with my kids while visiting friends in Ottawa.

“I used to explain why it didn’t work out by describing the job this way:

“You have a desk in a tiny cubicle in the White House press area, and you’re attached to it by a 60-foot leash, which limits how far you are allowed to go to talk to White House staff, although you do have a telephone. Projecting from the ceiling above your desk is the open end of a laundry chute. From time to time a load of dirty laundry drops out of the chute and onto your desk. Your job is to sort through the dirty laundry and deduce from that and the people willing to answer your phone calls what’s really going on in the areas your leash won’t let you reach.

“That’s not really a fair description, and I would never have put it that way if I had wanted to be a full-time political reporter. But while I liked political reporting, and covered Congress and most national political conventions, I preferred social issue reporting. Social issue reporting allowed more freedom to write compellingly about the systems that trouble so many people’s lives. . . .”

Among Carter’s legacies will be one that directly affects journalists: the Rosalynn Carter Fellowships for Mental Health Journalism.

Named for the Carter White House’s first lady, the awards seek “to develop a diverse cohort of better-informed journalists who can more effectively report on mental health and substance use across evolving and emerging platforms.” Such journalists of color as Yanick Rice Lamb, John Head, David Dent and Marissa Evans have been recipients.

“President Carter made a point of interacting with the journalism fellows at our annual meetings,” Head, a member of the 1999-2001 fellowship class, messaged Journal-isms. “In remarks and in individual conversations with us, he stressed the importance of the program’s mission. That mission included having diversity among those awarded fellowships and giving preference to projects that shined a light on the mental health needs of underserved communities. That’s why there are so many journalists of color on the fellowship roster.”

Rosalyn Carter has said, “Informed journalists can have a significant impact on public understanding of mental health issues, as they shape debate and trends with the words and pictures they convey. They influence their peers and stimulate discussion among the general public, and an informed public can reduce stigma and discrimination.”

In August 2015, then-columnist James Ragland (pictured) assessed Carter for his Dallas Morning News column.

In August 2015, then-columnist James Ragland (pictured) assessed Carter for his Dallas Morning News column.

“The world could use more men like Jimmy Carter,” he began.

“Sure, his politics and presidency may not be everyone’s cup of tea. Those periodic rankings by presidential scholars typically aren’t kind to him.

“But whether you consider Carter an ‘average’ president or worse, which is where most of these lists peg Carter, you’d be hard-pressed to find fault with his personal life, or the ambitious humanitarian agenda he pursued after losing his re-election bid in 1980.

“The peanut farmer who became one of the most powerful political figures in the world still calls Rosalyn, his wife of 69 years, the best thing that ever happened to him.

“Excuse me for thinking that’s just awesome. . . .”

- Atlanta Journal-Constitution: Remembering Jimmy Carter — The life and legacy of the man from Plains

- Faye Anderson, phillyjazz.us: Jimmy Carter (1924-2024) (Jan. 5, 2025)

- Bill Barrow, Associated Press: Jimmy Carter’s life intersected with slavery’s legacy. His record on Civil Rights is complicated (Jan. 8, 2025)

- CiberCuba: Jimmy Carter and his lesson of democracy to Fidel Castro in the historic speech given in Havana

- Mary C. Curtis, Roll Call: Jimmy Carter’s version of being a man should still mean something (Jan. 3)

- Deji Elumoye, This Day, Nigeria: [Nigerian President Bola] Tinubu Mourns Ex-US President, Jimmy Carter (Dec. 30)

- Emil Guillermo: Emil Amok’s Takeout: Jimmy Carter’s Sunday School Lesson (Jan. 2, 2025)

- HuffPost: President Jimmy Carter Authors New Bible Book, Answers Hard Biblical Questions: Science, Gays, Women, War And The Bible: President Jimmy Carter Answers The Hard Questions (March 19, 2012)

- Journal-isms: A Slight Course Correction (on death of Ronald Reagan) (June 9, 2004)

- Journal-isms: Ed Bradley’s Lifetime Riff (Nov. 22, 2006)

- Colbert I. King, Washington Post: A president for D.C. (Dec. 31)

- Cheryl E. Mango, Inside Higher Ed: President Carter: Champion of HBCUs (Jan. 10)

- Jean Marbella, Baltimore Sun: Jimmy Carter’s legacy in Baltimore: hundreds of houses in Sandtown (Dec. 29)

- Askia Muhammad, Washington Informer: More Honors Due to President Jimmy Carter (July 14, 2021) (According to Jet magazine, in 1977, Askia became the first Black journalist to be called upon by Carter as president)

- National Urban League: National Urban League Mourns President Carter as “Rarest of Politicians” Driven by Faith and Ideals (Jan. 2)

- Stephanie Nolen, New York Times: Jimmy Carter’s Quiet but Monumental Work in Global Health (Dec. 30)

- NY Carib News: Jimmy Carter Passes at Age 100 – A True Friend to Jamaica (Dec. 30)

- Donna M. Owens, NBC News: Jimmy Carter’s single term in office was a springboard for Black women in politics (Dec. 30)

Richard Prince with Lamont King and Greg Carr, “Urban View Mornings,” Sirius XM: Black Journalists Will Figure in Carter’s Legacy –– the Conversation (video) (Jan. 3, 2025)

Richard Prince with Lamont King and Greg Carr, “Urban View Mornings,” Sirius XM: Black Journalists Will Figure in Carter’s Legacy –– the Conversation (video) (Jan. 3, 2025)

- Raul A. Reyes, NBC News: Jimmy Carter’s Latino legacy: He elevated record number of Hispanics in Washington (Dec. 30)

- Ben Sisario, New York Times: Jimmy Carter and Motown Founder Berry Gordy’s Surprising Connection (Dec. 30)

- Gabriela Henriquez Stoikow, 285 South: How Jimmy Carter helped create the U.S.’s modern-day refugee resettlement system (Jan. 8, 2025)

- Ernie Suggs, Atlanta Journal-Constitution: Jimmy Carter’s musician friends rocked politics Musicians helped raise money, campaigned for former governor, president (paywall) (Jan. 2)

- Jessica Washington, The Root: Jimmy Carter’s Strange and Complicated Legacy With Black America

- Kimmy Yam, NBC News: Jimmy Carter remembered for launching 1st Asian Pacific American Heritage Week (Dec. 30)

Jan. 5, 2025, Update: Social Media Postings

View this post on Instagram

Statement by Former President Obama and Michelle Obama

For decades, you could walk into Maranatha Baptist Church in Plains, Georgia on some Sunday mornings and see hundreds of tourists from around the world crammed into the pews. And standing in front of them, asking with a wink if there were any visitors that morning, would be President Jimmy Carter – preparing to teach Sunday school, just like he had done for most of his adult life.

Some who came to hear him speak were undoubtedly there because of what President Carter accomplished in his four years in the White House – the Camp David Accords he brokered that reshaped the Middle East; the work he did to diversify the federal judiciary, including nominating a pioneering women’s rights activist and lawyer named Ruth Bader Ginsburg to the federal bench; the environmental reforms he put in place, becoming one of the first leaders in the world to recognize the problem of climate change.

Others were likely there because of what President Carter accomplished in the longest, and most impactful, post-presidency in American history – monitoring more than 100 elections around the world; helping virtually eliminate Guinea worm disease, an infection that had haunted Africa for centuries; becoming the only former president to earn a Nobel Peace Prize; and building or repairing thousands of homes in more than a dozen countries with his beloved Rosalynn as part of Habitat for Humanity.

But I’m willing to bet that many people in that church on Sunday morning were there, at least in part, because of something more fundamental: President Carter’s decency.

Elected in the shadow of Watergate, Jimmy Carter promised voters that he would always tell the truth. And he did – advocating for the public good, consequences be damned. He believed some things were more important than reelection – things like integrity, respect, and compassion. Because Jimmy Carter believed, as deeply as he believed anything, that we are all created in God’s image.

Whenever I had a chance to spend time with President Carter, it was clear that he didn’t just profess these values. He embodied them. And in doing so, he taught all of us what it means to live a life of grace, dignity, justice, and service. In his Nobel acceptance speech, President Carter said, “God gives us the capacity for choice. We can choose to alleviate suffering. We can choose to work together for peace.” He made that choice again and again over the course of his 100 years, and the world is better for it.

Maranatha Baptist Church will be a little quieter on Sundays, but President Carter will never be far away – buried alongside Rosalynn next to a willow tree down the road, his memory calling all of us to heed our better angels. Michelle and I send our thoughts and prayers to the Carter family, and everyone who loved and learned from this remarkable man.

More than 40 people were on the Zoom call on Feb. 19, 2023, with Rep. James Clyburn, D-S.C., and Dennis Brownlee, founder of the African American Irish Diaspora Network; 76 others watched on Facebook. (Credit: YouTube)

Clyburn Lauds Carter on Judgeships, Showing ‘How to Lose’

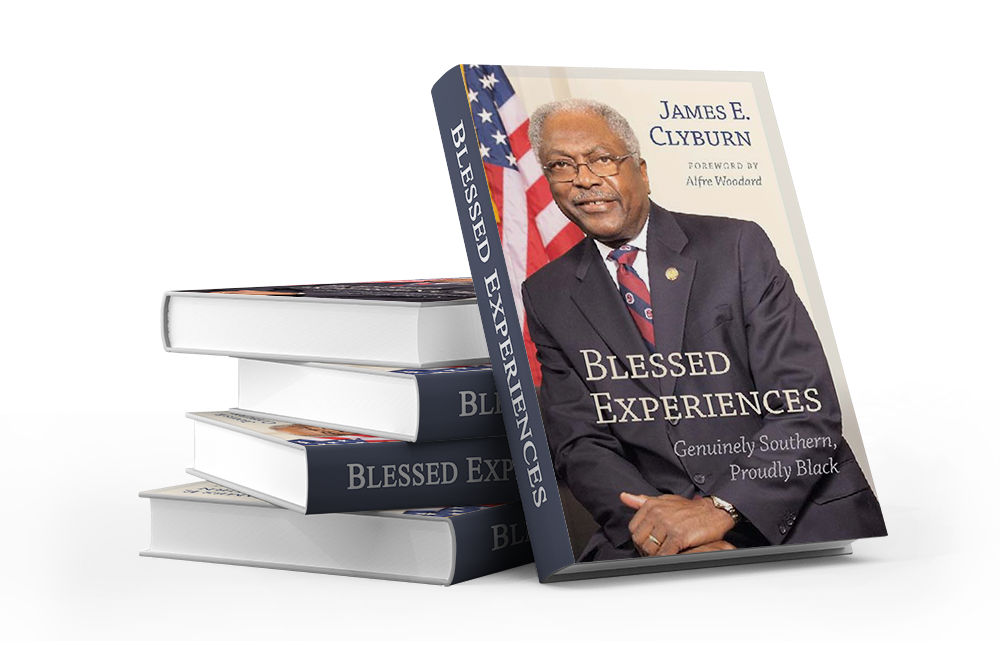

Jimmy Carter should be remembered as a president who showed people “not just how to win, but how to lose,” Rep. James Clyburn, D-S.C., the House assistant Democratic leader, told the Journal-isms Roundtable on Feb. 19, 2023. Clyburn also said Carter’s record-setting appointments of federal judges of color is too often overlooked.

Clyburn was asked in the Zoom conversation what the former president’s legacy would be, and how we should think about Carter’s presidency and post-presidency.

Clyburn responded:

“When I wrote my memoirs, I called it, as you can see, “Blessed Experiences: Genuinely Southern, Proudly Black.“

“That name was not by accident, it was by experiences. An experience I had when I was in the governor’s office, and I heard a white legislator, after saying something that I considered to be offensive.

“And I approached him about it. He said to me, ‘You must understand, I’m a Southerner.’

“And I approached him about it. He said to me, ‘You must understand, I’m a Southerner.’

“Well, I didn’t think that being a Southerner gives you rights to be racist, because I, too, am a Southerner, and because of my experiences I have a set of actions, just like Jimmy Carter — Jimmy Carter’s experiences growing up in Plains, Ga., in a majority-Black community.

“He came to the conclusion, upon becoming governor, that there were certain things taking place in Georgia that should not take place, especially as it related to those people that he grew up with.

“So Jimmy Carter taught us not just how to get elected, because he did a great job of that going out . . . disrupting everybody’s conventional wisdom. Winning the Iowa contest. And going on to become the Democratic nominee, and breaking a stranglehold.

“He taught us how to win.

“But when he lost, he taught us how to lose.

“And he became . . . the real public servant after having lost his re-election, a much better public servant than he was before.

“And one of those things, if you want to find out exactly the impact that he’s had, not just the work he’s done with building houses for Habitat for Humanity, going around the world, observing elections, doing what he could to make sure elections were fair.

“But look at his appointments.

“Until [President] Biden, Jimmy Carter had the record on putting people of color on the judiciary.

“Just go take a look at the record. Most people don’t know that record, but that record is clear that he put more people of color into the federal courts, into the courts of appeal.

“Everything except the United States Supreme Court. And that’s why I decided to tell Joe Biden he needed to take that step. Jimmy Carter had done all the things we had done [but] had not done the Supreme Court, and so I think Jimmy Carter is going to go down as one who showed people not just how to win, but how to lose.”

According to the Encyclopedia of African American Society, edited by Gerald D. Jaynes, “During the administrations of Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford, no blacks were named to federal appeals courts. However, under President Jimmy Carter, the number of blacks in the federal judiciary soared. Carter appointed 38 African Americans to federal judgeships in just four years, accounting for some 15 percent of all his federal court appointments. Carter was also noted for the large number of Hispanic and female judges he appointed.

‘”The Carter administration represented a high-water mark for the appointment of black federal judges.”

- Char Adams, NBC News: Biden has appointed more Black federal judges than any other president

On Richard Parsons: What Race Has to Do With It

Dec. 27, 2024

High-Ranking Media Exec Was of Two Minds

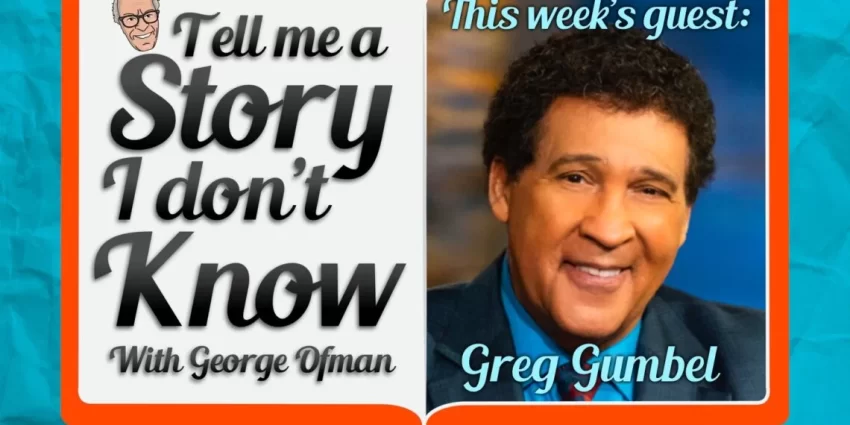

Sportscaster Greg Gumbel Dies of Cancer at 78

From 12/26: Gangs Kill Haitian Journalists Covering Story

Richard Parsons discusses the lack of CEO diversity with Jonathan Capehart on “Washington Post Live” a year ago. (Credit: Washington Post/YouTube)

High Ranking Media Exec Was of Two Minds

When Richard Parsons, “Serial Fixer of Media and Finance Giants,” died Thursday of bone cancer at 76, Black publications made sure to include his race in their headlines. In mainstream media, some did; some didn’t.

It was a reflection of the way Parsons himself viewed his race, and perhaps other Black CEOs as well.

Back in 2007, Ron Stodghill, then a Black New York Times reporter, wrote for his newspaper, “The subject of race has proven to be delicate for African-American executives, many of whom prefer to view themselves as — at least publicly — an ‘an executive who happens to be black.‘ They have earned the right through hard work, they say, to be judged on their merits.”

On Thursday, Stephen Galloway wrote for the Hollywood Reporter, “Parsons was for many years the highest-ranking African American in any media company, though that was a distinction he frequently played down. He advised young African Americans to focus on their new opportunities.”

And yet this exemplar of business success was clearly Black in his orientation. “Parsons, whose love of jazz led to co-owning a Harlem jazz club, also served as Chairman of the Apollo Theater and the Jazz Foundation of America. And he held positions on the boards of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, the American Museum of Natural History and the Museum of Modern Art in New York City,” wrote Anick Jesdanun and Michael R. Sisak for the Associated Press.

The AP’s own headline was, “Richard Parsons, prominent executive who led Time Warner and Citigroup, dies at 76.”

But in the New York Amsterdam News, part of the Black Press, that same AP story ran as “Richard Parsons, prominent Black executive who led Time Warner and Citigroup, dies at 76.”

Who was Dick Parsons? Below its “Serial Fixer” headline, the Times’ subhead read, “Mr. Parsons’s lengthy résumé is a catalog of corporate emergencies at Time Warner, Citigroup and the Los Angeles Clippers.”

Benjamin Mullin’s story began, “Richard D. Parsons, whose humane approach to business made him a serial troubleshooter at distressed companies such as Time Warner, CBS and Citigroup and a sought-after adviser at the highest echelons of American industry, died on Thursday at his Manhattan home. He was 76.

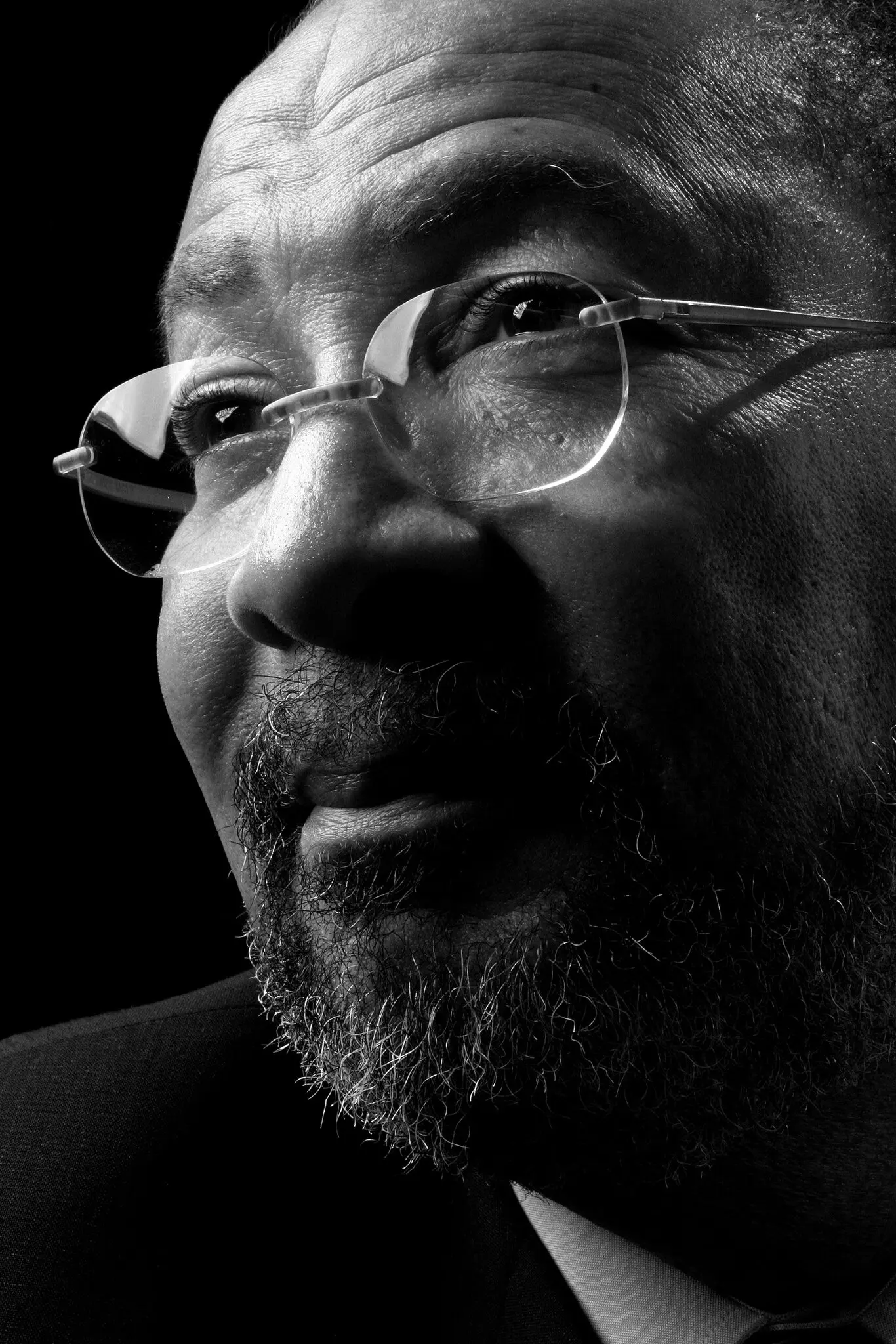

“Mr. Parsons’s (pictured, by Chester Higgins Jr./New York Times) winding career tracked the biggest companies in American media and finance — and the biggest problems. Time and again, he stepped in when things looked catastrophic and put his smooth leadership style to work, disentangling Gordian knots and assuaging discontented shareholders.

“Mr. Parsons’s (pictured, by Chester Higgins Jr./New York Times) winding career tracked the biggest companies in American media and finance — and the biggest problems. Time and again, he stepped in when things looked catastrophic and put his smooth leadership style to work, disentangling Gordian knots and assuaging discontented shareholders.

“Mr. Parsons, a jazz-loving oenophile who served on the board of the Apollo Theater and owned a Tuscan winery, rose to the top of the business world in an era when he was frequently the only Black executive in the boardroom. A self-described ‘Rockefeller Republican,’ Mr. Parsons spoke out on social justice issues in the wake of George Floyd’s murder in 2020, signed a letter protesting a 2021 law that imposed restrictions on Georgia voters, and was a founder of the Equity Alliance, a fund that backs early-stage ventures led by women and people of color.”

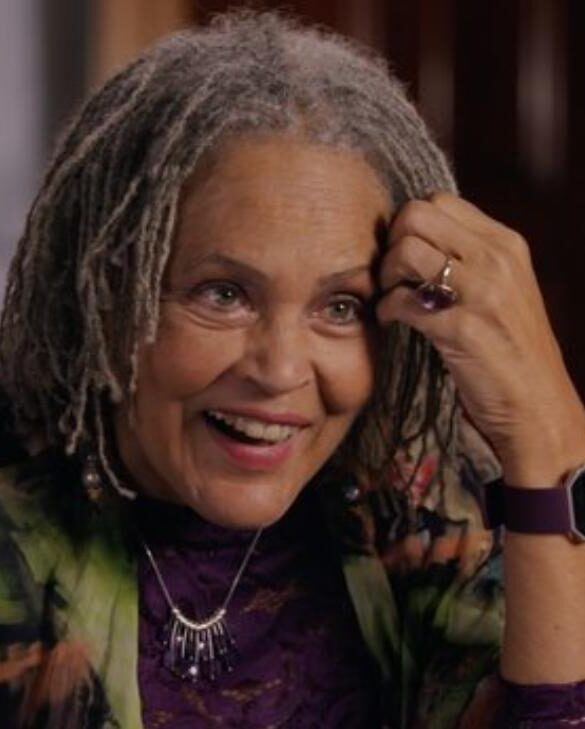

In 2007, Parsons was chairman and CEO of Time Warner when pioneering Black journalist Charlayne Hunter-Gault (pictured) quit CNN, a Time Warner property, because, she said at a special honors banquet of the National Association of Black Journalists, she felt CNN wouldn’t seriously cover Africa.

In 2007, Parsons was chairman and CEO of Time Warner when pioneering Black journalist Charlayne Hunter-Gault (pictured) quit CNN, a Time Warner property, because, she said at a special honors banquet of the National Association of Black Journalists, she felt CNN wouldn’t seriously cover Africa.

CNN correspondent Paula Zahn asked Parsons about diversity then for the CNN show “In the Money,” eliciting an answer that painted journalists as part of the problem.

“RICHARD PARSONS, CHAIRMAN & CEO, TIME WARNER: Progress happens slowly, I think the name of the game, I think it is to speed up the inevitable. I think diversity, as we’ve been calling it for the last 20 years, is inevitable reality in the American workplace. It is just a question of how quickly it happens. And it is happening. Not at the rate, speed, some of us would like, but it is happening. . . .

“ZAHN (pictured): In spite of how aggressive Time Warner has been, in putting these programs in place. Are you satisfied when you look around at your own company? Basically our newsroom, when you look behind me.

“ZAHN (pictured): In spite of how aggressive Time Warner has been, in putting these programs in place. Are you satisfied when you look around at your own company? Basically our newsroom, when you look behind me.

“PARSONS: The answer is no, I’m not satisfied. So we’re sort of redoubling our efforts. Although we’ve done, we’ve done virtually certain of this, probably as much as any major diversified media company in America, but yet the pace of change has still been slow. Interestingly enough the place where we have the most difficulty is among our journalists.

“ZAHN: Why do you think that is?

“PARSONS: I think because to a real extent, journalism is like priesthood, and certain experiences and schoolings and schools that you have to go to become a member of the club. And so, again, you have that pipeline problem, we have a number of people who are sort of moving up, who went to the right schools and had the right experiences. But it is breaking down those barriers that existed that aren’t even necessarily intentionally constructed, but it is the way things were.

“When you’re looking for new journalists, people that are looking go out and find, replicate themselves. They try to find folks that went to the same schools, same orientation, the same sort of prior experiences. And if — if you don’t have enough in this case minorities who had those experiences, they simply come back and say, ‘I can’t find qualified candidates.’ What we’ve done, we put a big focus on hiring people who can put the lie to that myth.

“ZAHN: You acknowledge that structural racism is alive and well in Corporate America.

“PARSONS: I assert that. That’s my belief.

“ZAHN: And the minorities are at distinct disadvantage. How do you in corporate culture confront the attitude that you’re expecting less of minorities, that you’re giving more opportunities than you are to the majority of the population. Clearly that’s something you’ve heard, I’ve read it in emails.

“PARSONS: That is very interesting. I don’t know if you’ve had any chance to get exposed, we’ve hired a gal who is now from Harvard, her name is Mazoran Benotchy [phonetic spelling] and she’s done a lot of work on what people’s subconscious perceptions are. And they aren’t even aware of these different ways they think about people, depending on their ethnicity, depending on their gender, depending on their race, so you have to — first thing you have to do is sort of surface that for them to look at it and understand it, it exists, it is in their head. Then you engage them in how are we going to change?”

Still, some of the obituaries quoted from another interview Parsons gave in 1997 to Elisabeth Bumiller of The New York Times, who today is about to step down as the Times’ Washington bureau chief.

“Mr. Parsons, 48, has friends among the city’s black financial elite — he shoots clay pigeons with Kenneth Chenault, a vice-chairman of American Express, and John Utendahl, the founder of Utendahl Capital Partners — but he is often the only African-American at corporate board meetings and East Side dinners. Although he says he was by choice not especially visible during Mr. [Rudolph] Giuliani’s 1993 [New York mayoral] race because ‘I didn’t want to be positioned as the Mayor’s black guy,’ he insists that he never feels the stresses of other high-level black professionals who work in a white corporate world.

“To illustrate, he tells a story he has often told before, about a white liberal woman who asked him in the 1960’s to describe himself.

” ‘And I started by saying, “Well, I’m a lawyer,” and she said, ‘”Wrong! The defining quality for you is that you’re black. And you refuse to acknowledge that.” ‘ Mr. Parsons shrugged, crediting his father, who was an electrical technician at Sperry Rand on Long Island, for his own views.

”I can remember him saying to me when we were talking about the slogan ‘I’m black and I’m proud,’ ‘Now Richard, wouldn’t it strike you as odd if somebody said, ‘I’m Irish and I’m proud?’ I said, ‘Well, people do say that.’ He said, ‘Yeah, but think about that. If you’re going to take pride in anything, take pride in something you’ve accomplished. Don’t take pride in an accident of birth.’ So, hey, what can I say? For a lot of people, race is a defining issue. It just isn’t for me . . . It is, it is” — he pauses — ”like air. It’s like height. I have other things that I’m focused on.’ ”

To our benefit, others continue to be focused on diversity in the business world, such as McKinsey & Co., a global management consultant company headquartered in Washington.

“For almost a decade through our Diversity Matters series of reports, McKinsey has delivered a comprehensive global perspective on the relationship between leadership diversity and company performance,” the company said in its 2023 report, “Diversity Matters Even More.”

“For almost a decade through our Diversity Matters series of reports, McKinsey has delivered a comprehensive global perspective on the relationship between leadership diversity and company performance,” the company said in its 2023 report, “Diversity Matters Even More.”

“This year, the business case is the strongest it has been since we’ve been tracking and, for the first time in some areas, equitable representation is in sight. Further, a striking new finding is that leadership diversity is also convincingly associated with holistic growth ambitions, greater social impact, and more satisfied workforces.

“At a time when companies are under extraordinary pressure to maintain financial performance while navigating a rapidly changing business landscape, creating an internal culture of transparency and inclusion, and transforming operations to meet social-impact expectations, the good news is that these goals are not mutually exclusive. On the contrary, our research suggests a strong, positive relationship between them. And in an increasingly complex and uncertain competitive landscape, diversity matters even more.”

So, yes, that Parsons was Black was important for journalists and readers to know — high up.

And so should they know of Parsons’ perseverance and optimism. “The sky’s the limit,” he told Fortune magazine in 2016. “Those barriers that were almost impenetrable a generation ago, certainly two generations ago, are gone. There are other structural things that we need to do in our society to level the playing field, but you can go from the top to the bottom almost regardless of race, origin creed or sexual orientation.”

- Austin Fuller, Current: PMJA [Public Media Journalists Association] report points to shortcomings in newsroom diversity efforts (Dec. 18)

- Roy S. Johnson, al.com: Dick Parsons, pioneering CEO, mentor and once my boss, was a singular brother

Greg Gumbel, ” One of the elder statesmen of sports broadcasting,” appears on “Last Word in Sports Media Podcast” in 2022.

Sportscaster Greg Gumbel Dies of Cancer at 78

“The family of former New York Knicks broadcaster Greg Gumbel announced his passing at the age of 78 on Friday,” Geoff Magliocchetti reported for Sports Illustrated.

” ‘He passed away peacefully surrounded by much love after a courageous battle with cancer,’ Gumbel’s family said in a statement to CBS. ‘Greg approached his illness like one would expect he would, with stoicism, grace, and positivity. He leaves behind a legacy of love, inspiration and dedication to over 50 extraordinary years in the sports broadcast industry; and his iconic voice will never be forgotten.’ “

Gumbel joined CBS in 1988 for the first of two stints, serving as the host for studio coverage of the NFL, college baseball, basketball, and football, MLB, NASCAR, and the Olympic Games. After CBS lost NFL rights in 1994, he would then hold similar duties at NBC, notably serving as the primary play-by-play man for the National League baseball playoffs during MLB’s return from a strike-shortened season in 1995. Gumbel was also on the mic for more NBA games and also hosted the peacock network’s NFL studio coverage (as well as the 1996 Summer Olympics.

“A second stint at CBS awaited in 1998 when the network returned to the NFL. Gumbel was called upon to serve as the play-by-play man for its top games and he became the first African-American to serve in such a role for a major American championship event when he narrated Super Bowl XXXV between the Baltimore Ravens and New York Giants. . . .

“Gumbel is survived by his wife Marcy and daughter Michelle, as well as his brother and fellow journalist Bryant.”

According to the Gumbel family Facebook page, “Gumbel Family is a Creole family from the Seventh Ward in New Orleans, Louisiana by way of Germany, Africa, and Santo Domingo in the Dominican Republic/Haiti. Ancestors came to America and established themselves in Pointe-a-la-Hache, LA and in New Orleans.”

- Seth Davis, hoopshq.com: Farewell to my friend Greg Gumbel

- Hallie Golden, Chicago Tribune: Greg Gumbel, a Chicago native who spent more than 50 years in sports broadcasting, dies from cancer at 78

- Rashad Milligan, NOLA.com: Greg Gumbel, a broadcasting legend from New Orleans, has died at the age of 78

[btnsx id=”5768″]

To subscribe at no cost, please send an email to journal-isms+subscribe@groups.io and say who you are.

Facebook users: “Like” “Richard Prince’s Journal-isms” on Facebook.

Follow Richard Prince on Twitter @princeeditor

Richard Prince’s Journal-isms originates from Washington. It began in print before most of us knew what the internet was, and it would like to be referred to as a “column.” Any views expressed in the column are those of the person or organization quoted and not those of any other entity. Send tips, comments and concerns to Richard Prince at journal-isms+owner@

View previous columns (after Feb. 13, 2016).

View previous columns (before Feb. 13, 2016)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2018 (Jan. 4, 2019)

- Book Notes: Is Taking a Knee Really All That? (Dec. 20, 2018)

- Book Notes: Challenging ’45’ and Proudly Telling the Story (Dec. 18, 2018)

- Book Notes: Get Down With the Legends! (Dec. 11, 2018)

- Journalist Richard Prince w/Joe Madison (Sirius XM, April 18, 2018) (podcast)

- Richard Prince (journalist) (Wikipedia entry)

- February 2018 Podcast: Richard “Dick” Prince on the need for newsroom diversity (Gabriel Greschler, Student Press Law Center, Feb. 26, 2018)

- An advocate for diversity in the media is still pressing for representation, (Courtland Milloy, Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2017)

- Morgan Global Journalism Review: Journal-isms Journeys On (Aug. 31, 2017)

- Journal-isms’ Richard Prince Wants Your Ideas (FishbowlDC, Feb. 26, 2016)

- Richard Prince with Charlayne Hunter-Gault, “PBS NewsHour,” “What stagnant diversity means for America’s newsrooms” (Dec. 15, 2015)

- Book Notes: Journalists Follow Their Passions

- Book Notes: Journalists Who Rocked Their World

- Book Notes: Hands Up! Read This!

- Book Notes: New Cosby Bio Looks Like a Best-Seller

- Journo-diversity advocate turns attention to Ezra Klein project (Erik Wemple, Washington Post, March 5, 2014)

1 comment