And Other Tales of Black Women’s Media Issues

Homepage photo credit: Lifetime/MSN

[btnsx id=”5768″]

And Other Tales of Black Women’s Media Issues

It came to the Associated Press as a request for a book review. It was 2010, and Danielle L. McGuire had written “At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance — a New History of the Civil Rights Movement From Rosa Parks to the Rise of Black Power.”

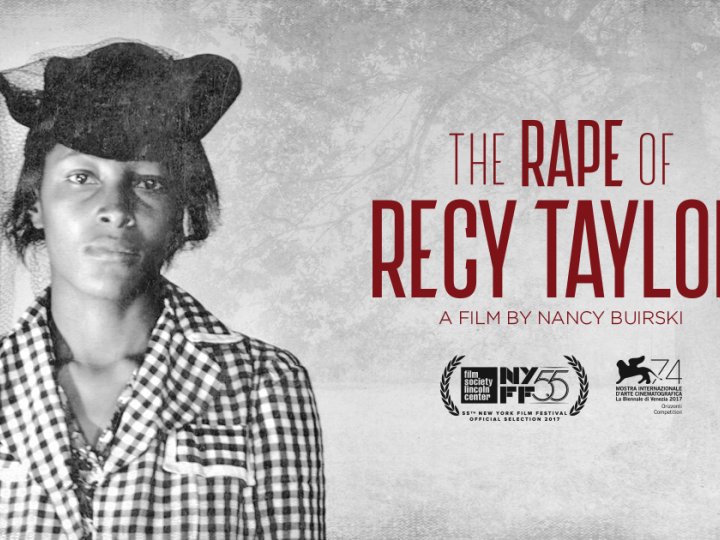

But inside the book was the story of Recy Taylor, a 24-year-old Black woman who was gang-raped by white men when she was walking home from a church revival in her small Alabama town on the evening of Sept. 3, 1944.

When Sonya Ross, then the AP’s race and ethnicity editor, and Errin Haines (pictured), then a reporter in the AP’s Atlanta bureau, started talking, Ross remembered declaring, “Screw the book review, let’s find this lady, because the logical question was, ‘How do you feel about the lack of justice for your case?’

When Sonya Ross, then the AP’s race and ethnicity editor, and Errin Haines (pictured), then a reporter in the AP’s Atlanta bureau, started talking, Ross remembered declaring, “Screw the book review, let’s find this lady, because the logical question was, ‘How do you feel about the lack of justice for your case?’

“Errin tracked Recy Taylor. And the question to her, ‘Would you like an apology?’ something that simple, led to an amazing thread of reporting that was done. This wonderful lady Recy Taylor had received an apology from her hometown and an apology from the state of Alabama.

“She had been the subject of a documentary, and by the time she passed away a few years ago, she was well aware that she was loved, and that she was appreciated and there was somebody on her side.

“And really that’s what any of us want when we cover these stories,” Ross told the Journal-isms Roundtable Zoom session on Sunday afternoon, Nov. 7. “When we put our voices out there, or when we go out there with an open ear to hear what our sisters are saying, and that is why it is so important to have discussions like . . . we’re having now and I hope that they will continue going forward. . . .

“That was amazing, amazing work.”

The lesson, attendees believed, was what can happen when Black women control the narrative.

Fifty-nine people were on the Zoom, with another 85 watching on Facebook. (Credit: YouTube)

Ross, who retired from the AP in 2019 after 33 years, including notable service as a White House correspondent, is founding editor of the website blackwomenunmuted.com. She was part of a panel moderated by Nichelle Smith, enterprise editor for racism and history at USA Today; Haines, editor-at-large at The 19th; dream hampton, showrunner and executive producer of the 2019 “Surviving R. Kelly” documentary series; and Yanick Rice Lamb, publisher of fierceforblackwomen.com and journalism professor at Howard University.

Fifty-nine people were on the Zoom, with another 85 watching on Facebook and 82 tuning in the reposting on YouTube as of the following Sunday, Nov. 14. Only 10 of those on the Zoom call were men, with others opting for watching an NFL game, an issue raised disapprovingly by the women in attendance, who said one should be able to do both.

You can watch the Roundtable video here or click on the image above.

Ross surfaced another issue with wider significance — undercoverage of news about Black women seeking political office.

“It started with a vengeance really, although it was happening before,” Ross (pictured) continued. “It started with a vengeance in 2017 with that outsized Black female vote participation in Alabama that lifted a Democrat,” Doug Jones, “to the U.S. Senate. Exit poll data . . . found that 98 percent turnout by Black women, the strongest and most loyal participation of any voting demographic that was measured in that election.

“It started with a vengeance really, although it was happening before,” Ross (pictured) continued. “It started with a vengeance in 2017 with that outsized Black female vote participation in Alabama that lifted a Democrat,” Doug Jones, “to the U.S. Senate. Exit poll data . . . found that 98 percent turnout by Black women, the strongest and most loyal participation of any voting demographic that was measured in that election.

“And there was lots of focus on it, lots of talk about it. Virtually no follow-up, because what happened right after that 98 percent is there were 70 Black women on various ballots, and Alabama the following year in 2018, and without actual media attention paid to that, they didn’t get the publicity they deserved, ergo so many of them did not get elected. So here we are in 2021 with the sisters still holding up a revolution, and very little focus being given to that.

“So while there is a large applause for the accomplishment of Kamala Harris, being elected vice president of the United States and really the highest office that any woman has held, we still have so much holding us back . . . And so much that needs to be reported that’s not getting reported . . . it’s still an under-told story. And it’s so very important for us to be out there reporting our own story, controlling that narrative, because we can bring the focus to that narrative that’s necessary.”

Haines said in introducing herself as editor at large of the 19th, founded in January 2020, “Part of the reason we started this newsroom [was] with the idea that political journalism had been too white and too male for too long.”

hampton is now best known for “Surviving R. Kelly,” the 2019 documentary series on Lifetime that renewed the interest that led to the R&B singer’s trial and conviction for sexual exploitation of a child, racketeering, bribery and sex trafficking.

Thirteen incarcerated men helped co-direct dream hampton’s visceral documentary about life in prison. (Credit: YouTube)

hampton allowed that she is much more than that series. “You might guess that I’m tired of talking about ‘Surviving R. Kelly,’ ” she said. “That same year, I did a six-part documentary series — I’m at BET — called ‘Finding Justice,’ that had nowhere near the amount of eyes on it that ‘Surviving R Kelly’ did.” “Finding Justice” examined police brutality and voting rights.

hampton did other relevant work for HBO. ‘It’s a Hard Truth, Ain’t It‘ was filmed at Indiana’s Pendleton Correctional Facility, following 13 incarcerated men as they studied filmmaking as a vehicle to explore their memories, as well as how they ended up with decades-long sentences.Despite Kelly’s conviction, the news media are not giving abusive Black men the attention they deserve, hampton said. “It became clear that there wasn’t going to be a shift in this ‘pimp culture’ that celebrates R. Kelly, if not celebrates him then at least looks the other way. That kind of shift I’m hoping happens, but I don’t see it as something that’s on the horizon,” the documentarian added.

In the week following his guilty verdict, Kelly’s music saw double-digit growth in streams and a triple-digit growth in sales, the Houston Defender reported.

hampton (pictured) continued, “You know I remember The New York Times published 100 people who had lost their jobs or their position or power because of the #MeToo movement. Two of them were Black.

hampton (pictured) continued, “You know I remember The New York Times published 100 people who had lost their jobs or their position or power because of the #MeToo movement. Two of them were Black.

“One of them was Bill Cosby. And so in our minds, though, we have this idea as Black folks that there’s been this over-indexing on targeting Black men, and I know that’s connected to a history. We brought up Ida B. Wells. Her work is largely about Black men being falsely accused of sexual violence. But at the same time, this was a movement that actually wasn’t talking about people who’ve been accused, like AJ Johnson, like Russell Simmons.

“I can think of a half dozen men who haven’t had the kind of spotlight put on them that, say, Jeffrey Epstein or Harvey Weinstein has. . . .

” We have wrongly thought that this is over-indexed on targeting Black men, and I do hope that changes, but sometimes these narratives can be much stronger than the truth.”

The Times story has since been updated; hampton says her point remains.

What’s not over-indexed is coverage of everyday Black women, Lamb said.

“We continue to see in news that there aren’t enough everyday women being covered in some of the women who are on the ground and behind the scenes . . . We see a lot of women who are already in the spotlight. Sometimes in coverage we see a disproportionate coverage of celebrities, and then some of the everyday women have been covered in terms of Covid 19 as being frontline workers, essential police, things like that.

“But . . . after that pandemic disappears, we definitely want to see more of that going forward, and we hope this is not just a spurt. Because, you know, women have been doing these things . . . for years, for decades. . . . It’s nice to have this moment, but we also remember seeing some of the initial [negative] coverage of Michelle Obama, and how that felt to a lot of Black women. . . .”

Smith (pictured) recalled that Obama “was on the one hand vilified in one hand and [on the other hand] celebrated, and it seemed — as if to me at least — as if the next administration worked very hard to remove all trace of her.”

Smith (pictured) recalled that Obama “was on the one hand vilified in one hand and [on the other hand] celebrated, and it seemed — as if to me at least — as if the next administration worked very hard to remove all trace of her.”

Lamb cited gender-gap reports from the Women’s Media Center and the Associated Press Sports Editors, and “Color Caste and the Public Sphere: Black journalists who joined television networks from 1994 to 2014,” a 2018 study from Howard University professors Indira S. Somani and Natalie Hopkinson. “Some of that was also looking at the pressure to have their hair conform or their dress or other aspects of their personality or their appearance conform to the norms [of] their stations or their networks,” the study said.

The treatment of Black women over the years amounts to human rights violations, retired journalist Kenneth Walker told the group, worthy of consideration by the United Nations. Walker called the United States an “active crime scene.”

“There are several processes throughout the country, taking evidence and hearing testimony about a number of anti-Black atrocities,” Walker messaged afterward.

“Law, police violence, medicine are just three areas being explored. The plan is to present the evidence to the United Nations in support of an international branding of the U.S. as guilty of crimes against humanity. That’s what I meant by active crime scene. The media, including most Black journalists, are ignoring these processes. And we shouldn’t be.” He sent a link to this story.

Ross was thinking similarly. “Maybe what we need to do as a people is to take our clues from South Africa, where our industry is concerned. Why can’t we have a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to take testimony from journalists over the generations, about the impact of being in this industry? And what it does to their psyches, our psyche, collectively and individually as Black Americans?

“I think that sort of information gathering is not dependent upon any media organization to make their people available for it. And it would be the people who are on the receiving end of the discrimination articulating the problem.”

The Roundtable began with a toast to Mira Lowe, who started the previous week as dean of the FAMU School of Journalism and Graphic Communication (scroll down). In addition to getting acquainted with the school and her primary duty of fundraising, Lowe said she was “looking [at] how we can better tell our story. FAMU has a very storied history. The school produces quality alumni, but I’m not sure we’ve done a great job of telling the story and all the accomplishments of our alumni and our current student body, so [we’ll] be looking to do more storytelling as a school of storytellers.”

We toasted Neil Foote and Rochelle Riley, Journal-isms Inc. board members who have been selected for induction to the Hall of Fame of the National Association of Black Journalists.

We congratulated Fergus Shiel, managing editor of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, which in October made news worldwide when it premiered “The Pandora Papers,” its latest investigation, conducted by a team of journalists around the globe who looked at the world of offshore finance and the people — and countries — who suffer when illicit money goes offshore. Shiel called it the biggest journalism project in history, with 600 journalists and 117 countries from 150 publications involved.

Kamesha Laurry, Borealis Racial Equity in Journalism Fund legal fellow at the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, introduced herself. Her work focuses on identifying, supporting and addressing the legal needs of journalists, reporters and documentary filmmakers of color.

Still, it was the main discussion that hit home for many. “This has been one of the most relevant panels you have ever had. I am on the verge of tears,” Hazel Trice Edney, founder of the Trice Edney News Wire, said before asking her question.

Riley wrote in the chat room, “We should do the Women Takeover quarterly.”

Kathy Roberts Forde, co-editor of the forthcoming “Journalism and Jim Crow: White Supremacy and the Black Struggle for a New America,” the topic of the upcoming Dec. 12 Roundtable, wrote, “This panel is extraordinary — and all of you panelists are a gift and,” she added, “please God changing this world through your work.”

- Inside Climate News: Sonya Ross Joins Inside Climate News as Managing Editor

[btnsx id=”5768″]

To subscribe at no cost, please send an email to journal-isms+subscribe@groups.io and say who you are.

Facebook users: “Like” “Richard Prince’s Journal-isms” on Facebook.

Follow Richard Prince on Twitter @princeeditor

Richard Prince’s Journal-isms originates from Washington. It began in print before most of us knew what the internet was, and it would like to be referred to as a “column.” Any views expressed in the column are those of the person or organization quoted and not those of any other entity. Send tips, comments and concerns to Richard Prince at journal-isms+owner@

View previous columns (after Feb. 13, 2016).

View previous columns (before Feb. 13, 2016)

-

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2018 (Jan. 4, 2019)

- Book Notes: Is Taking a Knee Really All That? (Dec. 20, 2018)

- Book Notes: Challenging ’45’ and Proudly Telling the Story (Dec. 18, 2018)

- Book Notes: Get Down With the Legends! (Dec. 11, 2018)

- Journalist Richard Prince w/Joe Madison (Sirius XM, April 18, 2018) (podcast)

- Richard Prince (journalist) (Wikipedia entry)

- February 2018 Podcast: Richard “Dick” Prince on the need for newsroom diversity (Gabriel Greschler, Student Press Law Center, Feb. 26, 2018)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2017 — Where Will They Take Us in the Year Ahead?

- Book Notes: Best Sellers, Uncovered Treasures, Overlooked History (Dec. 19, 2017)

- An advocate for diversity in the media is still pressing for representation, (Courtland Milloy, Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2017)

- Morgan Global Journalism Review: Journal-isms Journeys On (Aug. 31, 2017)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2016

- Book Notes: 16 Writers Dish About ‘Chelle,’ the First Lady

- Book Notes: From Coretta to Barack, and in Search of the Godfather

- Journal-isms’ Richard Prince Wants Your Ideas (FishbowlDC, Feb. 26, 2016)

- “JOURNAL-ISMS” IS LATEST TO BEAR BRUNT OF INDUSTRY’S ECONOMIC WOES (Feb. 19, 2016)

- Richard Prince with Charlayne Hunter-Gault,“PBS NewsHour,” “What stagnant diversity means for America’s newsrooms” (Dec. 15, 2015)

- Book Notes: Journalists Follow Their Passions

- Book Notes: Journalists Who Rocked Their World

- Book Notes: Hands Up! Read This!

- Book Notes: New Cosby Bio Looks Like a Best-Seller

- Journo-diversity advocate turns attention to Ezra Klein project (Erik Wemple, Washington Post, March 5, 2014)

When you shop @AmazonSmile, Amazon will make a donation to Journal-Isms Inc. https://t.co/OFkE3Gu0eK

— Richard Prince (@princeeditor) March 16, 2018

![]()

3 comments