Jesse Jackson Now Allowed on Page One

Homepage photo and still images from Journal-isms Roundtable by Sharon Farmer/sfphotoworks

Support Journal-ismsLeRae Umfleet, who studied the Wilmington, N.C., white riot of 1898, said, “It’s amazing to see how political propaganda in newspapers can turn to bullets in the streets.”

Jesse Jackson Now Allowed on Page One

In 1969, the year he joined the Chicago Tribune, columnist Clarence Page says the paper had an unwritten rule that Jesse Jackson could not appear on Page One.

In many newspapers from our past, when there were pages dedicated to “Negro News,” the publications had to make room for that page, which was zoned for Black neighborhoods. So newspapers took out the Business page for those parts of town. That was “on the assumption that our Black readers have no interest in business news,” said Hank Klibanoff, co-author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning “The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation.”

In 1964’s “Freedom Summer,” veteran journalist Roger Witherspoon wrote in the Zoom chat room, “white reporters went to Mississippi just to cover what happened to white kids registering Blacks” to vote. “There were 6 people killed that summer — the youngest a 14-year-old boy who was beaten to death with bats. Yet most people only know about 3 civil rights workers who were killed, and they probably would not know about” James Chaney, an African American, “if he hadn’t been with 2 white guys at the time he was killed.”

The Journal-isms Roundtable, held Sunday to hear from the authors of the new “Journalism and Jim Crow: White Supremacy and the Black Struggle for a New America,” edited by Kathy Roberts Forde and Sid Bedingfield, was full of such I-didn’t-know-that moments, from the attendees as well as the authors.

At least 63 people were on the Zoom call, with more watching on Facebook. You can watch the video on YouTube.

Michael Hill, a retired editor at the Washington Post, called the session an “amazing mash-up of genealogy, journalism and history!” It prompted story ideas. It reignited discussion of the need to redefine “objectivity.” It resurfaced the observation that for Black people, journalism and activism were synonymous, as D’Weston Haywood of Hunter College in New York (pictured), one of the book’s contributors, told the group.

Michael Hill, a retired editor at the Washington Post, called the session an “amazing mash-up of genealogy, journalism and history!” It prompted story ideas. It reignited discussion of the need to redefine “objectivity.” It resurfaced the observation that for Black people, journalism and activism were synonymous, as D’Weston Haywood of Hunter College in New York (pictured), one of the book’s contributors, told the group.

At least 63 people were on the Zoom call, with more watching on Facebook. (Credit: YouTube)

Many of the attendees lived that history, or discovered it from their own personal reporting. Veteran journalist Angela Dodson, descended from the Dodson and Hairston families, recounted how her relatives kept in touch over the generations, concluding that “a lot of the mythology we have about slavery is not true. We are not scattered, at least my family is not scattered. Never has been, and we are very fortunate that one of the reasons is we were owned by one of the richest slave-owning families in America that always kept their people kind of intact.”

Dodson began her discussion by noting that “in terms of newspapers, they actually profited off of slavery. . . . There are all kinds of ads, there were slave sales for however long slavery was, but after the Civil War, people posted ads looking for the relatives they’d lost that had been sold into slavery somewhere. So newspapers are complicit in slavery and complicit in the failure of Reconstruction and . . . made their profits, to some extent, the ones that are old enough, off of these conditions, and we shouldn’t let them off the hook for that.”

As many on the call pointed out, the past bears heavily on the present.

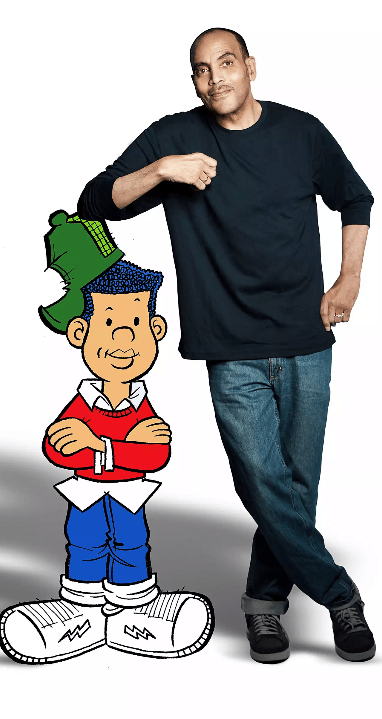

Honored were Ray Billingsley (pictured), the cartoonist who draws the “Curtis” comic strip. He was named cartoonist of the year by the National Cartoonists Society, the first African American in the 75-year-history of that award. “I feel energized! I haven’t been around so many intelligent journalists in…ever,” Billingsley messaged afterward, adding that he feels frustrated as one of the few Black syndicated cartoonists in his field.

Honored were Ray Billingsley (pictured), the cartoonist who draws the “Curtis” comic strip. He was named cartoonist of the year by the National Cartoonists Society, the first African American in the 75-year-history of that award. “I feel energized! I haven’t been around so many intelligent journalists in…ever,” Billingsley messaged afterward, adding that he feels frustrated as one of the few Black syndicated cartoonists in his field.

“I can’t name any Black people that work in high positions in any syndicate. Not one,” he told the group. “My main mission now is just to inspire other people. And people who are young and people who are older. People, oldsters like me,” said Billingsley, who is 64. “To get them to express their creative side and to try to join the ranks, and help chip away at these boundaries.”

Wayne Dawkins, former newspaper journalist who teaches at Morgan State University’s School of Global Journalism and Communication, received the group’s toast two days after the announcement that he had won this year’s Barry Bingham Sr. fellowship, an award given by the News Leaders Association “in recognition of an educator’s outstanding efforts to encourage students of color in the field of journalism.” Dawkins pledged to “continue to teach, coach and inspire student talent.”

Other journalism instructors were present. Scholars — the Minorities and Communication Division of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (AEJMC) — co-sponsored the Roundtable.

The “Jim Crow” authors outlined the shameful past that today’s newspapers must overcome, and a history that has helped fuel today’s resistance to the mainstream media’s definition of “objectivity.” Objective in whose eyes?

“A piece of the story that has been widely overlooked is the role of the white press, white newspaper editors and publishers in the South — during Reconstruction and for generations after – and the role they played in building white supremacist political economies and social orders in the South, along the way using the tools of racial terror to consolidate their power,” co-editor Forde (pictured) told the group.

“A piece of the story that has been widely overlooked is the role of the white press, white newspaper editors and publishers in the South — during Reconstruction and for generations after – and the role they played in building white supremacist political economies and social orders in the South, along the way using the tools of racial terror to consolidate their power,” co-editor Forde (pictured) told the group.

Those publications worked with business leaders “to support policies and laws to entrench segregation,” Forde said.

She and others added that Jim Crow existed in Northern newspapers as well.

Also among those present was LeRae Umfleet, who works for the state of North Carolina. She chronicled the story of the Wilmington, N.C., white riots of 1898, in which the Black newspaper was torched and Black leaders chased out of town.

“My work on 1898 showed me that the newspapers in North Carolina are completely culpable for the violence that happened on the streets in Wilmington, and Josephus Daniels, one of the leading newspaper editors in the state, was rewarded,” Umfleet said. “Financially, politically, and in every other way possible. Because of his work on 1898. . . . It’s amazing to see how political propaganda in newspapers can turn to bullets in the streets.”

But as white supremacists organized, so did others, said Haywood. He said his book chapter “elevates the Black press as a crucial site of Black people’s activism, organizing and political thought, centered on fighting white supremacy and actualizing a citizenship and rights rooted in real democracy. . . .They named it a New America.”

Haywood also said, “For Black people at this time, and certainly still to this day, journalism and activism were synonymous, as Black people resisted with protest journalism that often put their lives at stake in the course of building a counter-public that exposed the white supremacist project for what it was. And this form of resistance often goes overlooked in long histories of Black resistance that typically focus on Black armed struggle.”

One soldier in that struggle, Jessie Max Barber, is highlighted in Blair L.M. Kelley’s (pictured) chapter in “Jim Crow.” Barber was the founder of the Voice of the Negro, a short-lived journal founded in 1904.

One soldier in that struggle, Jessie Max Barber, is highlighted in Blair L.M. Kelley’s (pictured) chapter in “Jim Crow.” Barber was the founder of the Voice of the Negro, a short-lived journal founded in 1904.

“J. Max Barber ends up chronicling so much of what we can know about Black life at the turn of the 20th century,” Kelley said. “He becomes the foremost journalist of the streetcar boycott movement, in which in 25 different cities African Americans protested the segregation of trains and streetcars. So many of these boycotts were tremendously successful.”

Kelley noted that another attendee, Bala James Baptiste of Miles College, had pointed out that the New Orleans Times-Picayune editorial board did not report on the civil rights actions of the 1950s and ‘60s. Kelley said that “the same was happening in this time period in the 1900s.” She relied on Black-press accounts in her research.

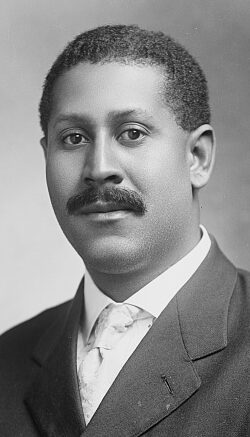

“They were sending these stories to J. Max Barber (pictured), who was then sharing them. They had a circulation of 15,000 by 1906, this small journal. It was such an important voice, such an intertwined effort in creating a culture of protest.”

“They were sending these stories to J. Max Barber (pictured), who was then sharing them. They had a circulation of 15,000 by 1906, this small journal. It was such an important voice, such an intertwined effort in creating a culture of protest.”

And in 1906, Kelley continued, when the Atlanta Race Massacre took place, “he stays in the streets to capture the stories of people trying to survive…at risk of his own life and is sending those stories forward.”

Kelley said threats forced Barber to flee to Chicago, where he published a full chronicle of what happened in Atlanta. He eventually left the profession and became a dentist and then an activist in Philadelphia after the death of Booker T. Washington.

“Imagine what we could know if he had been allowed to speak. Imagine what we could know if Ida B. Wells had never been driven from the South, imagine what we could know if so many journalists hadn’t been silenced or killed in the effort to tell these truths.”

DeNeen Brown (pictured), a Washington Post reporter and University of Maryland professor, heads a student project about the history of newspaper racism, “Printing Hate.”

DeNeen Brown (pictured), a Washington Post reporter and University of Maryland professor, heads a student project about the history of newspaper racism, “Printing Hate.”

“It is so important that we who are descendants of enslaved Black people take control of the narrative to really try to explain the generational pain and trauma that we experience,” she said. To that end, Brown said she insisted that the university hire Black journalists to work with the students, and it did.

Joseph Torres, of Media 2070: An Invitation to Dream Up Media Reparations, said the issue is, “How can we create media, a media system where Black folks have an abundance of media platforms where they can tell their own stories?. . .”

Thankfully, that’s happening, said Page, of the Chicago Tribune. “I’m delighted to see this vigorous activity on the web, particularly among journalists of color and communities of color, and just a lot of communities that didn’t have much of a voice before, do have a voice now. And I think we need to orient ourselves now toward this next century. . . . Democracy is always under assault, [whether] we were talking about racial lens or another lens, it’s always under assault. . . .

“This whole critical race theory is just the latest Willie Horton . . . gimmick . . . using human fears as a rallying tool.

“That’s what is happening here. And what are we supposed to be about as journalists? Educating people to the point where they’re less afraid. . . . I’m happy to see this debate over objectivity. How do we deal with it? I think that’s really the wave of the future for us, and this poses a big challenge for us.”

Contributing: Shelvia Dancy

- Flora Drury, BBC: New Zealand’s Stuff news group apologises for anti-Maori bias (Dec. 5, 2020)

- Journal-isms: L.A. Times Apologizes for Racist Past (Sept. 22, 2020)

- Journal-isms: On ‘Reverse Underground Railroad,’ Black Kids Were Stolen Off the Street (4th item, on advertising to recover slaves) (Dec. 24, 2019)

- Journal-isms: When Media Again Helped Foment a White Riot (Jan. 17) (scroll down)

- Journal-isms: Should Washington Post Join in Mea Culpas? (Jan. 13) (scroll way down)

- Vicki Mabrey, “60 Minutes II,” CBS News: A Family In Black And White (on the Hairstons) (1999)

- Mark I. Pinsky, Poynter Institute: Maligned in black and white: Southern newspapers played a major role in racial violence. Do they owe their communities an apology? (2018)

- Cortlynn Stark, Kansas City Star: J.C. Nichols’ whites-only neighborhoods, boosted by Star’s founder, leave indelible mark (Dec. 22, 2020)

To subscribe at no cost, please send an email to journal-isms+subscribe@groups.io and say who you are.

Facebook users: “Like” “Richard Prince’s Journal-isms” on Facebook.

Follow Richard Prince on Twitter @princeeditor

Richard Prince’s Journal-isms originates from Washington. It began in print before most of us knew what the internet was, and it would like to be referred to as a “column.” Any views expressed in the column are those of the person or organization quoted and not those of any other entity. Send tips, comments and concerns to Richard Prince at journal-isms+owner@

View previous columns (after Feb. 13, 2016).

View previous columns (before Feb. 13, 2016)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2018 (Jan. 4, 2019)

- Book Notes: Is Taking a Knee Really All That? (Dec. 20, 2018)

- Book Notes: Challenging ’45’ and Proudly Telling the Story (Dec. 18, 2018)

- Book Notes: Get Down With the Legends! (Dec. 11, 2018)

- Journalist Richard Prince w/Joe Madison (Sirius XM, April 18, 2018) (podcast)

- Richard Prince (journalist) (Wikipedia entry)

- February 2018 Podcast: Richard “Dick” Prince on the need for newsroom diversity (Gabriel Greschler, Student Press Law Center, Feb. 26, 2018)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2017 — Where Will They Take Us in the Year Ahead?

- Book Notes: Best Sellers, Uncovered Treasures, Overlooked History (Dec. 19, 2017)

- An advocate for diversity in the media is still pressing for representation, (Courtland Milloy, Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2017)

- Morgan Global Journalism Review: Journal-isms Journeys On (Aug. 31, 2017)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2016

- Book Notes: 16 Writers Dish About ‘Chelle,’ the First Lady

- Book Notes: From Coretta to Barack, and in Search of the Godfather

- Journal-isms’ Richard Prince Wants Your Ideas (FishbowlDC, Feb. 26, 2016)

- “JOURNAL-ISMS” IS LATEST TO BEAR BRUNT OF INDUSTRY’S ECONOMIC WOES (Feb. 19, 2016)

- Richard Prince with Charlayne Hunter-Gault, “PBS NewsHour,” “What stagnant diversity means for America’s newsrooms” (Dec. 15, 2015)

- Book Notes: Journalists Follow Their Passions

- Book Notes: Journalists Who Rocked Their World

- Book Notes: Hands Up! Read This!

- Book Notes: New Cosby Bio Looks Like a Best-Seller

- Journo-diversity advocate turns attention to Ezra Klein project (Erik Wemple, Washington Post, March 5, 2014)

When you shop @AmazonSmile, Amazon will make a donation to Journal-Isms Inc. https://t.co/OFkE3Gu0eK

— Richard Prince (@princeeditor) March 16, 2018