FBI Said to Fear Earl Caldwell’s Truth-Telling

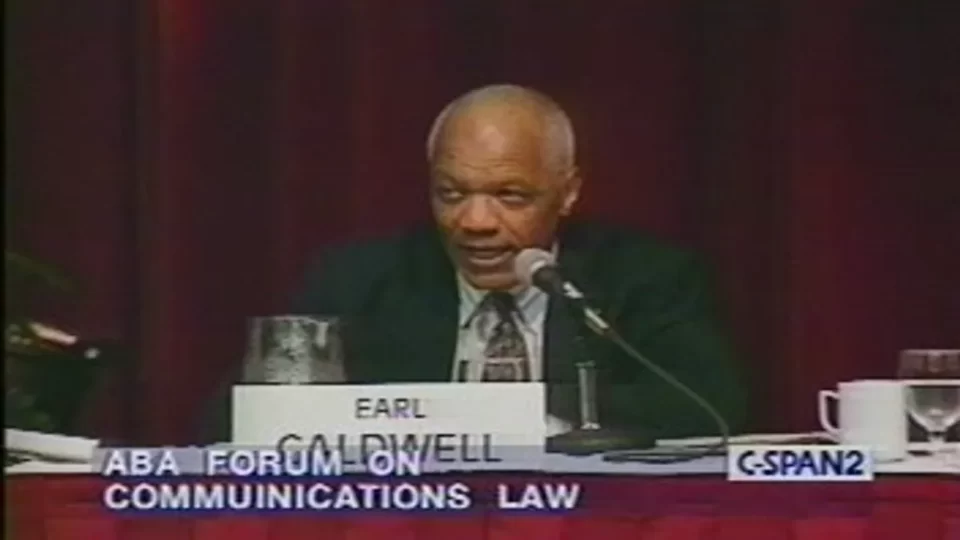

Homepage photo: Earl Caldwell speaks in 1997 about the extent and limits of journalistic privilege, especially regarding compulsive release, confidential sources and other unpublished material. (Credit: C-SPAN)

[btnsx id=”5768″]

Donations are tax-deductible.

The Journal-isms Roundtable on “When the Authorities Abuse Journalists” took place at a hybrid in-person and Zoom session at the Washington offices of the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, founded in 1970 in response to the Earl Caldwell case.

FBI Said to Fear Earl Caldwell’s Truth-Telling

The infamous Cointelpro program, the covert surveillance operation by government intelligence agencies that overrode citizens’ rights in pursuit of information, targeted a Black journalist in order to keep the news media from reporting fairly about the Black Panther Party, according to a First Amendment lawyer writing a book about Earl Caldwell, the targeted Black journalist.

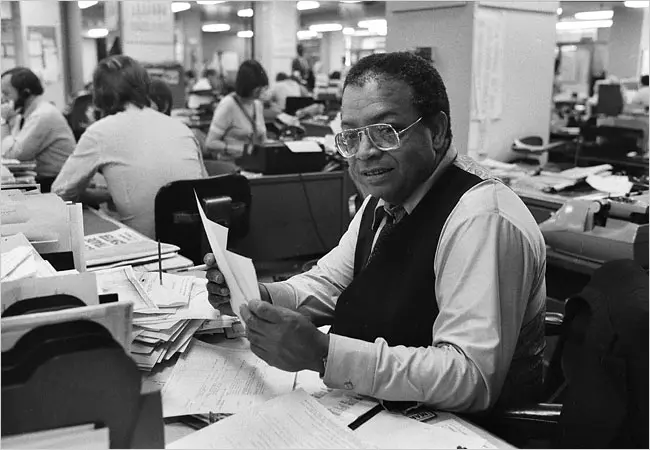

Caldwell was a New York Times reporter in 1970 when he was ordered to reveal his sources in the Black Panther organization to a federal grand jury, threatening his independence as a newsgatherer.

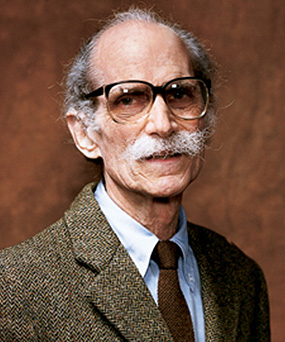

Lee Levine (pictured) the lawyer, made the Cointelpro connection at a meeting this month of the Journal-isms Roundtable at which both Levine and Caldwell appeared.

Lee Levine (pictured) the lawyer, made the Cointelpro connection at a meeting this month of the Journal-isms Roundtable at which both Levine and Caldwell appeared.

“What I came upon in my research for this book is that the subpoena for Earl most likely . . . was really not about wanting his testimony to assist the Justice Department in prosecuting the proud Black Panthers,” Levine said.

“It was really a part of an FBI operation known as Cointelpro, which took place in that period of time, that in this part was designed to destroy the Black Panthers,” he said, referring to the operation, officially the Counter Intelligence Program, which ran from 1956 to 1971.

“And one of the ways that they were fixing to do that was to cut off any kind of fair reporting about the Panthers that would tell especially the mainstream media and the predominantly white press the full picture of what the Panthers were about and what they were doing.

“And Earl, who had been sent to California in the fall of 1968, was doing that, and it really pissed off J. Edgar Hoover,” the longtime FBI director, “and so what I hope my book will show is that Earl was subpoenaed so that an atmosphere of distrust would arise between him and the Panthers, because the Panthers would not know — even if you refuse to testify before the grand jury when you went in the grand jury room, they wouldn’t know that for sure and that he would be cut off and be unable to report.”

As Time magazine has summarized, “The case made its way to the United States Court of Appeals, which ruled in Caldwell’s favor and agreed that he did not have to share his confidential information with the federal government. It was a short-lived victory, however, as the government appealed the case to the Supreme Court, and was taken up by the Court in combination with two other First Amendment cases in February 1972.”

Caldwell pursued the case with the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund and constitutional lawyer Anthony Amsterdam (pictured) when the Times did not fully back him. “While it filed briefs supporting Earl’s position at every stage of the case, it did not agree with his decision not to appear before the grand jury and vouch for the accuracy of his articles,” Levine messaged.

Caldwell pursued the case with the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund and constitutional lawyer Anthony Amsterdam (pictured) when the Times did not fully back him. “While it filed briefs supporting Earl’s position at every stage of the case, it did not agree with his decision not to appear before the grand jury and vouch for the accuracy of his articles,” Levine messaged.

CBS reporter Mike Wallace did testify before the grand jury about an interview he conducted with the Panthers’ Eldridge Cleaver.

In the Supreme Court’s eventual Branzburg v. Hayes ruling, announced on June 29, 1972, the high court ruled against Caldwell and other reporters. But the case became historic because the Supreme Court ruled for the first and only time on the issue of reporter’s privilege.

“The case had a fairly large impact on the journalism field because it meant that journalists do not have special protection,” Robert Richards, a media law professor at Penn State, told Time’s Josiah Bates last year. “They weren’t looked at as having more privilege than the average citizen when it came to grand jury testimony.

“The decision meant there was a possibility that Caldwell could go to jail, but the federal government never pursued him again. He continued to work at the Times. . . .”

The Journal-isms Roundtable on “When the Authorities Abuse Journalists” took place Oct. 1 at a hybrid in-person and Zoom session at the Washington offices of the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, which was founded in 1970 in response to the Caldwell case.

Fifty-seven were in attendance in person or on Zoom, with 98 having watched on Facebook as of Friday, and 90 on YouTube. You can watch the session here or in the embedded video above.

An additional video with the extended interview with Caldwell, questioned by retired Time columnist Jack E. White, Levine and this columnist, is here and is embedded above. It had been viewed 39 times by Oct. 20. Comedian Roy Wood Jr. opened the Roundtable, and his comments are discussed in this column.

One of those watching the video was Betty Medsger (pictured), a former Washington Post reporter who in 1971 received a huge trove of classified documents stolen from the Media, Pa., branch office of the FBI.

One of those watching the video was Betty Medsger (pictured), a former Washington Post reporter who in 1971 received a huge trove of classified documents stolen from the Media, Pa., branch office of the FBI.

The Post published some of the documents, and four decades later Medsger tracked down the perpetrators, whose identities had never been revealed, and wrote what was considered the definitive account of what she called “perhaps the most powerful single act of nonviolent resistance in American history.”

The burglary revealed to the public how the FBI served as “secret judge, secret jury, and secret warden” in its efforts to “intimidate people from exercising their right to dissent,” Publishers Weekly wrote in 2014.

Medsger messaged last week, referring to Levine, “I was stunned when he said during his brief comments . . . that the FBI effort to get Earl to testify was part of a COINTELPRO operation to keep the Panthers from being treated well in mainstream media. . . .

“I thought I learned all the essential awful stories about COINTELPRO when I wrote my book, but this one is new to me, and also very important.

“There’s an ironic twist in it for me. . . . as I sat at my desk the morning I received the stolen FBI files in March 1971, I was able to make the decision to write the stories despite the potential risk of being called before a federal grand jury largely because I remembered the risk Earl had taken — and was still taking — when he refused to cooperate with the FBI or to go before a grand jury. I decided this story was worth taking the risk he took.”

Another who was watching was Dorothy Tucker, who just completed two terms as president of the National Association of Black Journalists. “Extremely interesting session. I learned more about NABJ history and have a better understanding of the offerings of the Reporters Committee,” Tucker wrote on Facebook. “I look forward to connecting.”

In addition to hosting the Roundtable, the Reporters Committee explained its work and introduced Mayeesha Galiba (pictured) as its new NBCU News Group Race Equity in Journalism Legal Fellow. She is to focus on providing pro bono legal support for journalists of color and newsrooms led by people of color.

In addition to hosting the Roundtable, the Reporters Committee explained its work and introduced Mayeesha Galiba (pictured) as its new NBCU News Group Race Equity in Journalism Legal Fellow. She is to focus on providing pro bono legal support for journalists of color and newsrooms led by people of color.

Caldwell, whom Levine believes to be 90 (Caldwell has said he can’t be definitive), is living journalism history.

In addition to working as a reporter for The New York Times, he became a columnist for the Daily News in New York, a co-founder of the Maynard Institute for Journalism Education and endowed professor at Hampton University.

Caldwell described a 1970 meeting of 50 Black journalists at Lincoln University in Jefferson, Mo., and called it the start of the national Black journalists movement. Caldwell said he wanted to tell listeners “what happened there and how important that was in creating this sort of a unification of Black journalists.”

The Black journalists’ group’s first order of business would be a campaign of support for Caldwell, The New York Times reported. NABJ would not be founded until 1975.

A prior group of Black journalists in New York, organized in 1967 around Caldwell’s dilemma and took the name “Black Perspective,” without the word “journalist,” Caldwell recounted. Gay Talese, a star white reporter who would write “the classic inside story” about the Times, said he had never heard of a “Black journalist.” You were just “a journalist” at the Times. One of the Times’ senior Black reporters, Thomas A. Johnson, “said if it’s called Black, I can’t be in it.” Johnson said the Times, then edited by A.M. Rosenthal, “wouldn’t allow it. He said, ‘You could have an organization of all the Black people, but you couldn’t call it Black.’

“And they wouldn’t, they were reluctant to even use Black in describing people of color.”

The Roundtable took place less than a month after a group of press photographers reached a historic settlement with the New York City Police Department with an agreement “that has the potential to transform police conduct and training, especially regarding the First Amendment for both journalists and the general public,” as Lisa Marie Segarra wrote then for PetaPixel.com, a publication for photographers.

A release from the office of New York state Attorney General Letitia James added, “As a result of today’s agreement, the NYPD must improve its treatment of members of the press and improve reporters’ access to a protest to be able to record and report.”

Mickey H. Osterreicher, general counsel to the National Press Photographers Association, a visual journalist and a negotiator of the Sept. 5 agreement, joined the Roundtable, along with one of the abused photographers, Amr Alfiky, an Egyptian native who was apprehended by New York police in 2020 in Manhattan’s Chinatown neighborhood while filming NYPD officers.

Osterreicher was asked what journalists should do if they are abused by police. “Well, you should hopefully be working with somebody else so . . . you can watch each other’s back,” he replied.

“If you’ve got some type of recording device, keep recording, because it’s going to be a ‘he-said-she-said’ type thing and there is a presumption that the officer is telling the truth, and we found, unfortunately, that that’s not always the case.

“So having a video recording, even if the video’s not great, but the audio is as to what went on, be respectful.

“You know that you’re recording this, you want the police to look like they’re out of control, which oftentimes they are, where they’ve escalated the situation rather than de-escalated the situation.

“But it’s those kinds of things; make sure that you’ve got contact information. I suggest to people, at least our NPPA members, that they write my phone number down in indelible marker on their arm, cause we all rely on our phones now, and you’re not gonna have your phone and usually people don’t know the number, they just hit the number or ask it to send a number and dial it. So if you need to have a number, write that down, so somebody can contact somebody. It doesn’t have to necessarily be me directly.”

John C. Watson assigned his Communication Law class at American University to cover the session. Seventeen did the assignment properly, Watson messaged.

“Those who chose Amr [as their subject] were struck by his revelation that he was six years into the study of medicine when he left Egypt, became homeless and chose to formally study journalism. They also dwelled on his back injury and devotion to reporting breaking news. ‘I thought covering the George Floyd protest was more important to me than getting my cyst fixed.’ ‘I was working and bleeding at the same time.’ “

Now working for Reuters and on the Zoom from Dubai, Alfiky was asked how freedom of expression in Egypt compares with that in the United States.

“It’s unfortunate but it’s not as bad as it used to be,” he replied. During the tenure of Hosni Mubarak, president of Egypt from 1981 to 2011, “you wouldn’t even be able to say his name. Like if you say his name, you’re in trouble.

“But now things are slowly changing, I hope. But In the U.S., there is a free, like clear guideline, constitutional right. The First Amendment right. It’s friend. And it’s been a part of our practice for I don’t know how long now … It’s really sad to see that being violated by law enforcement. Regularly. Especially against journalists. And journalists of color in particular.”

On the Zoom from Texas was Eduardo Beckett, an immigration lawyer who in September helped secure, after 15 years, U.S. asylum for Mexican journalist Emilio Gutiérrez Soto.

The 15 years included being subjected to judges who said they didn’t believe Gutierrez was a journalist and undertaking multiple appeals. But there was also support from the National Press Club, the Committee to Protect Journalists, the Knight Wallace fellowship program at the University of Michigan and others in the journalism world.

“In this case, the power of the press worked, I believe,” Beckett said. “I really believe that the interference by the press in this case put a lot of pressure. And we’re able to get victory for him.

“But it shouldn’t be that hard. It shouldn’t take multiple lawyers and multiple lawsuits and FOIAs to win a case like that,” he said, referring to Freedom of Information Act requests.

“This case should have been won at the beginning. But it wasn’t. And that just shows you where we’re at.”

- Kenny Cooper, WHYY Philadelphia: How to break into the FBI: 50 years later, Media burglars get local honors (Aug. 23, 2021)

- Katherine Jacobsen, Committee to Protect Journalists: Tipping the scales: Journalists’ lawyers face retaliation around the globe (Oct.12)

- Journal-isms: An ‘Inspired’ Caldwell Leaves Hampton U., Has Plans (May 13, 2022) (scroll down)

‘[btnsx id=”5768″]

To subscribe at no cost, please send an email to journal-isms+subscribe@groups.io and say who you are.

Facebook users: “Like” “Richard Prince’s Journal-isms” on Facebook.

Follow Richard Prince on Twitter @princeeditor

Richard Prince’s Journal-isms originates from Washington. It began in print before most of us knew what the internet was, and it would like to be referred to as a “column.” Any views expressed in the column are those of the person or organization quoted and not those of any other entity. Send tips, comments and concerns to Richard Prince at journal-isms+owner@

View previous columns (after Feb. 13, 2016).

View previous columns (before Feb. 13, 2016)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2018 (Jan. 4, 2019)

- Book Notes: Is Taking a Knee Really All That? (Dec. 20, 2018)

- Book Notes: Challenging ’45’ and Proudly Telling the Story (Dec. 18, 2018)

- Book Notes: Get Down With the Legends! (Dec. 11, 2018)

- Journalist Richard Prince w/Joe Madison (Sirius XM, April 18, 2018) (podcast)

- Richard Prince (journalist) (Wikipedia entry)

- February 2018 Podcast: Richard “Dick” Prince on the need for newsroom diversity (Gabriel Greschler, Student Press Law Center, Feb. 26, 2018)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2017 — Where Will They Take Us in the Year Ahead?

- Book Notes: Best Sellers, Uncovered Treasures, Overlooked History (Dec. 19, 2017)

- An advocate for diversity in the media is still pressing for representation, (Courtland Milloy, Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2017)

- Morgan Global Journalism Review: Journal-isms Journeys On (Aug. 31, 2017)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2016

- Book Notes: 16 Writers Dish About ‘Chelle,’ the First Lady

- Book Notes: From Coretta to Barack, and in Search of the Godfather

- Journal-isms’ Richard Prince Wants Your Ideas (FishbowlDC, Feb. 26, 2016)

- “JOURNAL-ISMS” IS LATEST TO BEAR BRUNT OF INDUSTRY’S ECONOMIC WOES (Feb. 19, 2016)

- Richard Prince with Charlayne Hunter-Gault, “PBS NewsHour,” “What stagnant diversity means for America’s newsrooms” (Dec. 15, 2015)

- Book Notes: Journalists Follow Their Passions

- Book Notes: Journalists Who Rocked Their World

- Book Notes: Hands Up! Read This!

- Book Notes: New Cosby Bio Looks Like a Best-Seller

- Journo-diversity advocate turns attention to Ezra Klein project (Erik Wemple, Washington Post, March 5, 2014)

4 comments