An Excerpt: Book’s Preface Focuses on N.Y. Times

. . . Staples Recounts History of Newspaper Racism

Home page photo: Students from the International Reporting Program at the University of British Columbia working in Cameroon. (Credit: Global Reporting Centre)

[btnsx id=”5768″]

An Excerpt: Book’s Preface Focuses on N.Y. Times

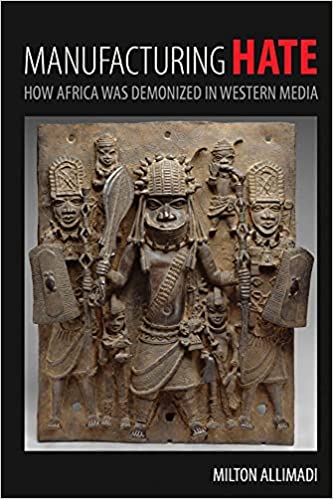

In June, Milton Allimadi, editor and publisher of the Black Star News newspaper in New York and adjunct professor of history at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, published “Manufacturing Hate: How Africa Was Demonized in Western Media” (Kendall Hunt publishers).

Allimadi wrote Journal-isms, “My book documents the demonization of Africa in Western Media beginning from the 18th century, when the so-called European ‘explorers’ went to ‘discover’ and rename rivers, lakes, and mountains in Africa that already had indigenous names: the book covers the era when newspapers like The New York Times, and magazines like National Geographic started sending writers to the continent, and the book concludes with more recent writings covering Africa in the 21st century.

“As you know, the so-called ‘explorers’ projected a racist image of Africa in order to justify enslavement and, later, colonial subjugation and exploitation. Subsequent writings about Africa simply adopted the racist template created by the European trespassers — the so-called ‘explorers.’

“For example, when The New York Times sent Pulitzer prize winning journalist Homer Bigart to cover decolonization in Africa in late 1959, this is what he said in a letter to his foreign editor from Africa, referring to Kwame Nkrumah: ‘I’m afraid I cannot work up any enthusiasm for the emerging republics. The politicians are either crooks or mystics. Dr. Nkrumah is a Henry Wallace in burnt cork. I vastly prefer the primitive bush people. After all, cannibalism may be the logical antidote to this population explosion everyone talks about.’ ”

By Milton Allimadi

Crude and Ugly

“Crude and Ugly Language”

— The New York Times’ Managing Editor Joseph Lelyveld, referring to some of the newspaper’s early African news coverage.

I wrote Manufacturing Hate — How Africa Was Demonized in Western Media to fight the stereotypical racist representations of Africans and people of African descent, and the ignorance and cover-ups that go with them.

I wrote Manufacturing Hate — How Africa Was Demonized in Western Media to fight the stereotypical racist representations of Africans and people of African descent, and the ignorance and cover-ups that go with them.

During my research, I encountered some gatekeepers who preferred to defend the status quo. I hope that this book can be an eye-opener for those who read it — that their takeaways will be transformative and insightful on many levels for all, including lay readers, students of history and journalism, as well as practicing journalists and editors, for whom this book may become both a teaching and learning tool.

The book illustrates how, historically, racism — and the manufactured hate that accompanies it — was deliberately used, and continues to be used, to rationalize and justify economic exploitation of Africans and people of African descent.

Africans are still referred to as “tribal” peoples, with all the attendant negative perceptions that spring from the word, sometimes with deadly consequences. When Tutsi insurgents invaded ethnically volatile Rwanda from Uganda in 1990 and the war degenerated into genocidal killings in 1994, Western media referred to the conflict as “tribal.”

In an infamous article published in its April 25, 1994, issue, Time magazine conjured up images of cannibalism by claiming that “tribal bloodlust” was fueling the war. Meanwhile, the Clinton administration blocked any significant intervention by the United Nations; after all, “tribal” wars are intractable and irresolvable.

Manufacturing Hate — How Africa Was Demonized in Western Media illuminates the process behind the “tribalization” of Africa. Originally, I had intended to write a magazine article entitled “Darkest Times in Africa,” focusing on the evolution of The New York Times’ coverage of Africa and how many of the stereotypes about Africa emerged. I first conducted the research in 1992 for my master’s thesis while I was a student at the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia University. During the course of my research, I gained access to Times’ archives and unearthed several racist letters that had been exchanged between the newspaper’s foreign news editor and the reporters sent to cover Africa.

One Times editor who was involved in some of the most virulent exchanges was Emanuel Freedman, foreign news editor from 1948 to 1964. A Times reporter, Homer Bigart, espoused similar racist sentiments in his letters. In one letter, when the Times sent Bigart to cover emerging independence movements in West Africa, he wrote to Freedman that he preferred writing about cannibals over Kwame Nkrumah, the hero of Ghana’s independence struggle and the country’s first post-colonial prime minister and later, president.

Freedman responded with similar venom in his own letters. I also discovered from the archival materials that concocted incidents that never occurred were inserted into New York Times articles about Africa to give them a “tribalistic” flavor. The archival documents I obtained enriched and complemented The New York Times articles that I had read, dating back to the nineteenth century.

At the conclusion of my research, the first magazine I submitted my master’s thesis to for publication was the Columbia Journalism Review (CJR); at the time I was under the impression that the publication was a foundation of journalistic integrity. My paper was accepted for publication on January 26, 1992, by an editor, Michael Hoyt.

My article did not appear in several subsequent issues of CJR. On April 27, I called Hoyt and demanded to know why my paper had not yet been published. I was surprised when Hoyt, in a rather timid tone, informed me that a decision had been made not to publish my paper. He said the editorial board, consisting of five members, “after long discussions,” had been deadlocked. Two editors voted in favor and two opposed publication. He claimed the executive editor at the time, Suzanne Levine, cast the decisive negative vote. When I asked why some editors were opposed, Hoyt said, “There was a feeling these things happened a long time ago.”

Of course, I was enraged and demanded to have my paper returned. I still recall the chill I felt when Hoyt asked me why I wanted it back. “After all,” I recall him saying, “it’s been extensively edited and it’s not the same as what you gave us.” I insisted that my paper be returned to me, and he finally acquiesced. To this day, I am convinced that I never would have gotten my paper back and discovered how the CJR editors had committed journalistic cowardice and betrayal had I not immediately gone to Hoyt’s office, which was located in the same building as the journalism school, from where I had called him, to retrieve it.

When I read the edited version of my paper, which was in galley form in preparation for publication, I found that the editors had inserted the following paragraph on my behalf, unbeknownst to me and without my consent: “Recently, the Times granted me access to its archives, including correspondences from the 1950s, when the paper sent Bigart to Africa on a temporary assignment. After studying the archival material, I interviewed several present and former Times reporters. The following excerpts from that material and from lengthy interviews are not intended as an indictment of the Times — whose African coverage has occasionally been distinguished — but as a means of highlighting a problem that all news organizations need to address.”

I could only conclude that the CJR editors were afraid of offending editors at the Times. I decided to do them a favor. On October 29, 1992, I sent a shorter version of my original master’s paper to the Times with a letter addressed to the publisher, Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, Jr. I wrote that a “bitter gripe” had lodged in my chest as a result of the CJR’s journalistic betrayal because of its editors’ fear of the Times. I had been made to feel as if I had committed a crime when, in fact, I had gone into the paper’s archives and discovered evidence of culpability by Times’ editors and reporters in perpetuating racist stereotyping of Africans.

Eventually, I received a letter from Joseph Lelyveld (pictured) then the Times’ managing editor and later executive editor. He wrote that he was responding on behalf of Sulzberger and that, indeed, my research had unearthed articles with “crude and ugly” language. He also argued that, on the other hand, the Times had published insightful articles about Africa through the years, and that he too had been involved in the coverage, first as a correspondent in South Africa and later as foreign news editor. I later met Lelyveld in person.

Eventually, I received a letter from Joseph Lelyveld (pictured) then the Times’ managing editor and later executive editor. He wrote that he was responding on behalf of Sulzberger and that, indeed, my research had unearthed articles with “crude and ugly” language. He also argued that, on the other hand, the Times had published insightful articles about Africa through the years, and that he too had been involved in the coverage, first as a correspondent in South Africa and later as foreign news editor. I later met Lelyveld in person.

Before my graduation, I felt a small measure of vindication when my paper won the James Wechsler Memorial Prize from the university. After graduation in May 1992, I sent my article to several publications including The Village Voice, The New Yorker, Atlantic Monthly, Harper’s, and New York Magazine. When all of them declined to publish, I could not help but recall the episode with the CJR. The best rejection came from the editor of The New Yorker. In a handwritten note on the typed letter — presumably the written note is not on the copy kept on file — he suggested that I submit the paper to Mother Jones, which also rejected it.

I concluded that the problem wasn’t the subject matter; it appeared each editor who reviewed the article was more concerned that she or he could be seen as responsible for embarrassing The New York Times. In the meantime, students who were aware of the paper invited me to speak about it, including at the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia and later at Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs. In February 2002, I presented the paper when I was invited to Williams College, in Massachusetts.

My paper received a warm reception and several students asked me when I would turn the material into a book. As it turns out, I had broadened the scope of my research over the years to include other publications in addition to the Times, such as National Geographic magazine, Time magazine, Newsweek, and The New Yorker.

My study now included the popular journals of the European travelers who “explored” Africa between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. These journals were the original media responsible for disseminating the racist representation of Africa throughout Europe, in the Americas, Asia, and even in Africa itself.

In 2019, filmmaker Zadi Zokou, a native of the Ivory Coast who lives in Massachusetts, produced “Black N Black,” a documentary on what African Americans and Africans living in the United States think of each other. He found misinformation on both sides. (Credit: YouTube)

Demonization of Africans was the handmaiden of conquest and colonization. I’m not here to romanticize Africa’s past. There were conflicts and there were also despotic regimes; yet no more so than in other regions. On the other hand, Africa is the source of all humankind. All human beings originated in Africa and migration — of Africans — to populate the rest of the world happened only within the last 100,000 years. There were spectacular achievements and great civilizations in Africa, such as Egypt, ancient Ghana, Songhai, Mali, Ethiopia, Nubia, Aksum, Zimbabwe, Kongo, Buganda, and many others. Many of them predate the formation of nations in Europe.

As my book shows, these realities were not reflected in any of the writings of the so-called explorers, the European colonial officials, and later professional journalists who wrote about Africa in the earlier era.

Their main task was to demonize Africans, to justify the violent conquest and subjugation that enabled resource plunder and labor exploitation.

Moreover, the portrayal of Africans as superstitious “savages” belied the fact that Europeans themselves were very experienced in some of the practices for which they denigrated Africans.

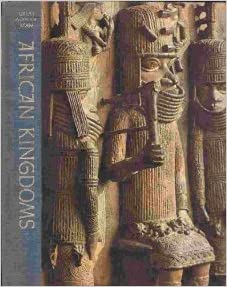

In African Kingdoms, Basil Davidson, a prominent British historian, wrote, “Africa, long thought of as breeding ground for the occult, was more than matched by Europe, with its own manias for alchemy, astrology and witch-burning. In the 15th century, superstitious parishioners often danced among the graves in churchyards . . . in hopes of protecting themselves from the plague — while the skulls of plague victims peered quizzically at them. During the same period, Germany was burning an average of two witches a day.”

In African Kingdoms, Basil Davidson, a prominent British historian, wrote, “Africa, long thought of as breeding ground for the occult, was more than matched by Europe, with its own manias for alchemy, astrology and witch-burning. In the 15th century, superstitious parishioners often danced among the graves in churchyards . . . in hopes of protecting themselves from the plague — while the skulls of plague victims peered quizzically at them. During the same period, Germany was burning an average of two witches a day.”

“Europeans,” Davidson added, “moreover, were constantly duped by promises of miraculous transformations and cures. Elixirs of life, magnets to attract diseases from the body, magic potions and healing fragments of the ‘true cross’ were common. Even such prominent intellectuals as Thomas Aquinas and Roger Bacon searched relentlessly for the philosopher’s stone, the mystical charm of alchemy supposed to transform dross into gold. Yet despite all their delusions, Europeans thought of themselves as paragons of dignity and sensibility — while regarding faraway Africans as frightened primitives and painted witchdoctors.”

Had I not been betrayed by the CJR, would I still have embarked on the journey that resulted in this book? I believe so. I had always been outraged by the negative representations of Africans and African descendants in Western media. I am not so naïve as to believe that any book will ever eliminate offensive and racist representations of black people or of any other non-white peoples for that matter. There are powerful entities and economic interests that benefit from the status quo.

Maintaining the false narrative, where Europeans are portrayed as the epitome of civilization while Africans as the obverse—a continent of permanently dependent inhabitants—serves a broad purpose; it sanitizes the historical crimes committed against Africans, from slavery and colonialism, and through the new-colonialism maintained in our modern era by the economic dependency imposed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank through “structural adjustment” programs.

At the same time, Manufacturing Hate — How Africa Was Demonized in Western Media can help readers understand the origins of the racist depictions of Africans, the motives behind them, and the consequences. It may also inspire young people to challenge the continued demonization of Africa, and other non-European societies, in Western media.

— Milton Allimadi, New York City, December 2020

. . . Staples Recounts History of Newspaper Racism

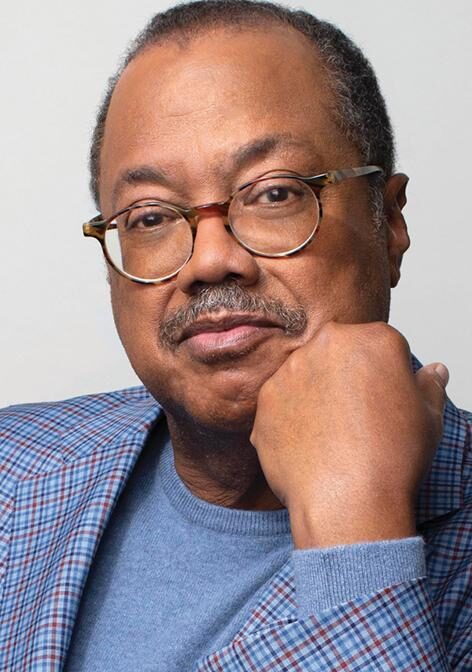

. . . A New York Times spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment, nor did several Black former Times journalists, but Paul Delaney (pictured), a retired senior editor who worked at the Times from 1969 to 1992, messaged, “wish i had access to those files & i cant wait to read the book…i’m not surprised by the racist exchanges. in fact, a fellow editor — white — once complained to me that he was shocked & disappointed when attending an all-white party thrown by a times editor on the east side, where attendees openly used racist comments about their black colleagues; they felt comfy doing it with no blacks around.

. . . A New York Times spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment, nor did several Black former Times journalists, but Paul Delaney (pictured), a retired senior editor who worked at the Times from 1969 to 1992, messaged, “wish i had access to those files & i cant wait to read the book…i’m not surprised by the racist exchanges. in fact, a fellow editor — white — once complained to me that he was shocked & disappointed when attending an all-white party thrown by a times editor on the east side, where attendees openly used racist comments about their black colleagues; they felt comfy doing it with no blacks around.

” i assumed it happened often & possibly still does. i am still bitterly disappointed about racism, whenever & wherever. but, this is america.”

Meanwhile, Times editorial writer Brent Staples (pictured) recounted the history of racism in newspapers in a column that went online Saturday headlined, “How the White Press Wrote Off Black America.“

Meanwhile, Times editorial writer Brent Staples (pictured) recounted the history of racism in newspapers in a column that went online Saturday headlined, “How the White Press Wrote Off Black America.“

Staples began, “Newspapers that championed white supremacy throughout the pre-civil rights South paved the way for lynching by declaring African Americans nonpersons. They embraced the language once used at slave auctions by denying Black citizens the courtesy titles Mr. and Mrs. and referring to them in news stories as ‘the negro,

‘the negress’ or ‘the nigger.’ . . .”

He concluded, “News organizations that were not moved to address this problem when the business represented a license to print money have come to see things differently since the business model began its collapse. The apology movement represents a belated understanding that these organizations need every kind of reader to survive. The challenge is that the gap news providers are eager to close is vast and was generations in the making.”

Joseph Torres (pictured) is senior director of strategy and engagement at the activist group Free Press, which has launched Media 2070, which includes “an essay that documents how anti-Black racism has been part of our media system’s DNA since colonial times.” It is asking the public for examples.

Joseph Torres (pictured) is senior director of strategy and engagement at the activist group Free Press, which has launched Media 2070, which includes “an essay that documents how anti-Black racism has been part of our media system’s DNA since colonial times.” It is asking the public for examples.

“I was thrilled to see Brent’s essay,” Torres messaged when asked to comment on Staples’ piece. “It was great. I hope there are more journalists who make this historical connection in understanding the political challenges we face today in our news media and media system.

“I think it is really important and critical that our nation reckons with the historical role that white-dominant media companies have played in protecting and upholding a white-racial hierarchy in our society. These companies have caused the Black community and other communities of color so much harm. And these harms have been reinforced by federal policy decisions that determine who can own and control our nation’s media and communications infrastructure.

“The Media 2070 team has been making progress on the policy front.” Reps. Jamaal Bowman, D-N.Y., Yvette Clarke, D-N.Y., and Brenda Lawrence, D-Mich., “recently called on the FCC to conduct an equity audit to investigate how its policy decisions have created inequities in media and telecom systems. And the Media 2070 team has also recently called on newsrooms to take a pledge to care for Black communities and Black journalists.”

- Journal-isms: How Media Fanned the Nation’s Racism (Oct. 19, 2020)

- Journal-isms: National Geographic Examines Racist Past (March 13, 2018)

[btnsx id=”5768″]

To subscribe at no cost, please send an email to journal-isms+subscribe@groups.io and say who you are.

Facebook users: “Like” “Richard Prince’s Journal-isms” on Facebook.

Follow Richard Prince on Twitter @princeeditor

Richard Prince’s Journal-isms originates from Washington. It began in print before most of us knew what the internet was, and it would like to be referred to as a “column.” Any views expressed in the column are those of the person or organization quoted and not those of any other entity. Send tips, comments and concerns to Richard Prince at journal-isms+owner@

View previous columns (after Feb. 13, 2016).

View previous columns (before Feb. 13, 2016)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2018 (Jan. 4, 2019)

- Book Notes: Is Taking a Knee Really All That? (Dec. 20, 2018)

- Book Notes: Challenging ’45’ and Proudly Telling the Story (Dec. 18, 2018)

- Book Notes: Get Down With the Legends! (Dec. 11, 2018)

- Journalist Richard Prince w/Joe Madison (Sirius XM, April 18, 2018) (podcast)

- Richard Prince (journalist) (Wikipedia entry)

- February 2018 Podcast: Richard “Dick” Prince on the need for newsroom diversity (Gabriel Greschler, Student Press Law Center, Feb. 26, 2018)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2017 — Where Will They Take Us in the Year Ahead?

- Book Notes: Best Sellers, Uncovered Treasures, Overlooked History (Dec. 19, 2017)

- An advocate for diversity in the media is still pressing for representation, (Courtland Milloy, Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2017)

- Morgan Global Journalism Review: Journal-isms Journeys On (Aug. 31, 2017)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2016

- Book Notes: 16 Writers Dish About ‘Chelle,’ the First Lady

- Book Notes: From Coretta to Barack, and in Search of the Godfather

- Journal-isms’ Richard Prince Wants Your Ideas (FishbowlDC, Feb. 26, 2016)

- “JOURNAL-ISMS” IS LATEST TO BEAR BRUNT OF INDUSTRY’S ECONOMIC WOES (Feb. 19, 2016)

- Richard Prince with Charlayne Hunter-Gault,“PBS NewsHour,” “What stagnant diversity means for America’s newsrooms” (Dec. 15, 2015)

- Book Notes: Journalists Follow Their Passions

- Book Notes: Journalists Who Rocked Their World

- Book Notes: Hands Up! Read This!

- Book Notes: New Cosby Bio Looks Like a Best-Seller

- Journo-diversity advocate turns attention to Ezra Klein project (Erik Wemple, Washington Post, March 5, 2014)

When you shop @AmazonSmile, Amazon will make a donation to Journal-Isms Inc. https://t.co/OFkE3Gu0eK

— Richard Prince (@princeeditor) March 16, 2018

![]()

5 comments