From a Member, What Disinformation Has Wrought

Homepage photo: Washington Post

[btnsx id=”5768″]

From a Member, What Disinformation Wrought

How would you like to go to work every day wondering whether your colleagues were in on a plot to kill you?

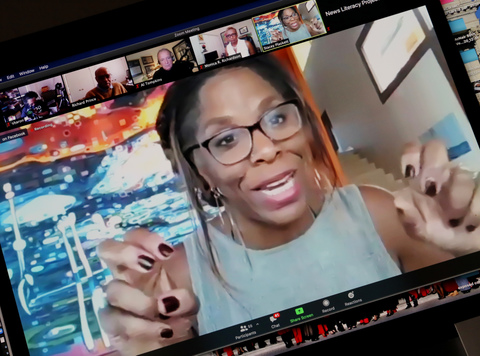

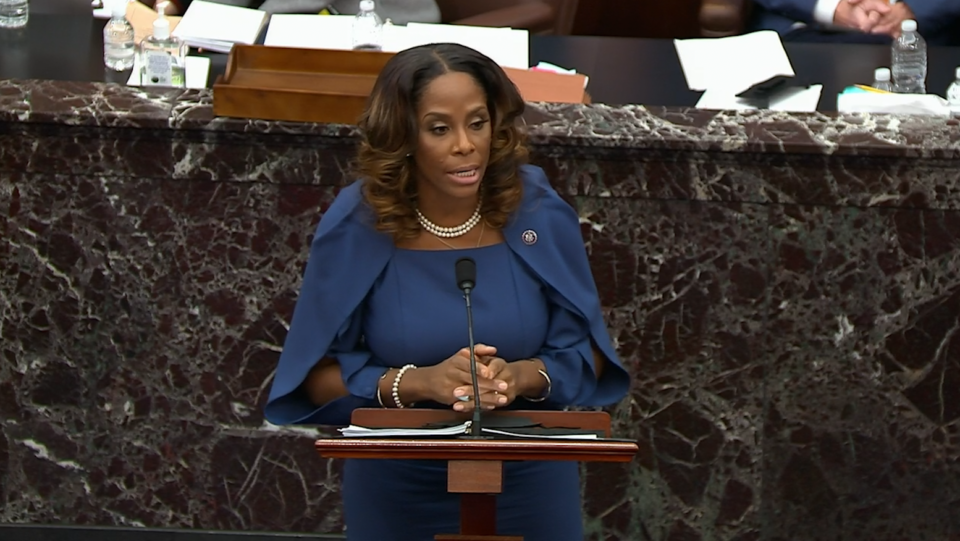

That’s the situation Delegate Stacey Plaskett of the U.S. Virgin Islands, a member of Congress and a House impeachment manager in January, says she and others at her workplace face. Her words have resonance as the nation Friday marked the 100th-day anniversary of the Jan. 6 insurrection, and the continuing clamor by Republicans for “bipartisanship” in the Democratic-controlled Congress.

“Right now, there’s even a philosophical question among members of ‘do I want to have my name on legislation with someone who’s a liar?” Plaskett told the Journal-isms Roundtable, convened March 21 to discuss the ramifications for journalists of disinformation, “who is someone who I believe was trying to kill me two months ago, because they were spreading lies, or who is a seditionist in my belief, or someone who wants to overthrow our government?

“So I know, in my office, you know, I’m considered a moderate . . . much more moderate than many of my Democratic colleagues, and I have a list of legislation that I previously co-sponsored with Republicans that I’ve told my leg’ [legislative] team, ‘hold off, because I have to come to grips with the notion that I’m actually going to work with that person, who previously, I may have had lunch with, who our daughters were pen pals. And now this joker, after the insurrection, still voted to object to the certification.

“So . . . I can’t just bring myself to even work on a piece of legislation with this person. And I’m considered a moderate, so I can’t even imagine what is happening in the minds of some of my more progressive left-of-myself members of Congress. It makes it really difficult.”

Who are the worst offenders? Plaskett was asked.

“Oh, I don’t want to say that,” she replied. But Plaskett said she could “do like, maybe . . . four hands with a group that, you know, I’m definitely not breaking any bread with, and at least 10 or a dozen that I probably wouldn’t even get into an elevator with at this point. That’s how stark and how tense it is right now.”

Plaskett has reason to be worried. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi has warned that if any Republican members of the House had aided the rioters as they sought to advance former president Donald Trump’s effort to overturn the election results, they would be punished.

A total of 139 House Republicans objected to certifying election results in certain states during the counting of Electoral College votes on Jan. 6, which was interrupted by a mob of Trump supporters who stormed the Capitol. They spread disinformation — that the election was “stolen.”

While members of Congress like Plaskett are victims of what’s now called the Big Lie, so are journalists. Rep. Ted Lieu, another of the impeachment managers, said in February that the media are among the enablers of Trumpism. Right-wing media paint an alternate view of reality. Trump voters accept it. They turn on any Republican who tries to deviate from that. Hence, Republicans stick with the Trump line. It makes it harder for journalists who seek the truth to be believed.

As Marty Baron prepared to retire as editor of The Washington Post at the end of February, he cited disinformation as the biggest threat to trust in journalism and to democracy. Disinformation affects not only the political arena, but the life-and-death responses to the COVID pandemic.

So what can journalists do about it? One step is to be smart about how disinformation is concocted, Al Tompkins of the Poynter Institute told the 60 who were on the Zoom call, and another 58 on Facebook Live. The recording can be viewed on YouTube.

We knew about Photoshop, but not so much about more recent technology. Tompkins showed a shot of Oprah Winfrey seated in front of a fireplace, across from former president Barack Obama. Winfrey was in Santa Barbara, Calif., and Obama was in Washington, but the viewer would think they were in the same room. Tompkins also displayed a widely circulated video of Pelosi seemingly slurring her words. Then he demonstrated how an Adobe Premiere editing machine allows the user to manipulate the pitch of the speaker’s voice and the speed of the delivery.

The Adobe also enables the user to remove or add elements of a photo or video at will, to create whatever impression he or she wants to the viewer. The user can zap a person out of the photo or add a bush where there was none. It’s called a “content aware fill,” and “there is no journalistic use of that, that I would defend . . . But once it’s out there, then people can use it for anything,” Tompkins said.

Some of the remedies go to journalistic practices, such as the “truth sandwich” and the “liar’s dividend.”

As the News Literacy Project has said, “Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society lays out the basics of how to correct the record, whether you’re an individual or a news outlet: Begin and conclude with the correct information, sandwiching the wrong information between. As Berkman puts it, ‘Make the truth, not the falsehood, the most vivid take-away.’

“That’s because repeated information sticks with us, whether the information is accurate or not. We rely on repetition. The more something is heard, the more it’s believed.”

Mike Webb (pictured) senior vice president of communications of the News Literacy Project, also spoke. It was four days before Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp signed that state’s restrictive voting laws.

Mike Webb (pictured) senior vice president of communications of the News Literacy Project, also spoke. It was four days before Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp signed that state’s restrictive voting laws.

“We issued a statement calling on state legislatures to base any changes that they’re making to their election laws on facts, because we’ve seen this rash of information or a rash of proposed legislation that is supposed to fix some of the election problems, but they’re based on the fiction that there were all these problems in the past election. And so . . . I think it’s very important for the journalists here to sort of share that reasoning with their audience and make sure that they understand these laws are being proposed to fix X, Y, and Z. But are they being proposed to fix something that’s not broken?”

In Georgia, at least, the project’s call seemed unsuccessful.

Webb said that while journalists might think that “when we write these things down, and we inform our audiences, that they’ll accept that and that they’ll act on that, because it’s factual, verified information. But I think what we have to remember are people are in filter bubbles, and that there’s a belonging for people.

“So there was a study recently that showed that people, even if they knew something was factually inaccurate, if it’s what their filter bubble believed, they would pass it along on their social channels. And so you have to really be aware that part of what you’re doing is trying to break that bubble. . . . And it’s very tough to crack that, because it’s an emotional belonging thing.”

Tompkins raised another issue: “To what extent do journalists make it difficult for elected officials to change their mind on important issues? How much would they fear being labeled a flip-flopper, so they dig in on illogical or unsupported views?”

The journalists on the call were riveted. “So besides going to credible sources and reporting on facts and the truth, a journalist’s job now includes detecting, decoding and publicly explaining the lies?” asked Ivan Roman, a former executive director of the National Association of Hispanic Journalists. “That’s something we all did and do in the reporting process, but now, given today’s dynamics, we have to publicly report on the lies also. That’s a normal part of the story now, correct? Does this mean that, unfortunately, we are giving more oxygen to the lies?”

“For me,” said Hazel Trice Edney, who runs the Trice Edney Wire news service, “this is an encouragement to — increasingly and wherever possible — resort to good old-fashioned shoe leather reporting. In other words, whenever possible, depend on your own photos, interviews, research and accuracy.”

“People are learning how to manipulate audio, images and video because all the ‘how-to’s’ are on YouTube,” Rebecca Aguilar (pictured), president-elect of the Society of Professional Journalists, wrote in the chat room.

“People are learning how to manipulate audio, images and video because all the ‘how-to’s’ are on YouTube,” Rebecca Aguilar (pictured), president-elect of the Society of Professional Journalists, wrote in the chat room.

Monica R. Richardson, who became executive editor of the Miami Herald on Jan. 1, also spoke of the need for journalists to go back to basics. “The most important thing Al said was go to the source. Look it up. Ask the question. And as simple as that seems, I think sometimes we realize we have to sacrifice things. We have to sacrifice being first on a story. We may have to make other sacrifices to making sure that we can go back to the basics and get people the information they need in a credible way.”

The Herald recently started working with a company called Subtext, she said. That’s a subscription messaging platform that allows organizations to text with their audiences, as a way to answers reader questions about the virus,” as Nieman Lab described it — without the “anything goes, true or not” environment of social media.

More than 500,000 people are subscribed to at least one of 600 hosts using Subtext, Nieman Lab’s Hanaa’ Tameez wrote in February.

It’s “like having a two way conversation — what is the question you have about COVID? And that is a credible relationship that we have with someone . . . a way of using technology to do one-on-one with someone who has a question.

“They type in a question and Google How do I blah, blah, blah, how do I find information about the vaccine? How do I get this effective vaccine? What do I know? But if we are able to establish and use tools that give us a direct relationship to have those conversations, I think . . .it makes it more powerful for us. . . . ”

In addition, Richardson noted that last fall, the Herald launched what it called an Election Ad Decoder. A Herald story then said, “By searching the Herald’s Election Ad Decoder, you can find out who paid for an ad, whether it contains false or misleading content, what data is being collected from you and where your money will go if you give. The Herald also worked extensively with academic experts to identify disinformation, hateful speech, foreign interference and content that promotes violence — flagging ads as such when they could jeopardize the integrity of the election.”

As the Roundtable is based in the District of Columbia, Plaskett was asked about D.C. statehood, now a live issue in Congress. She expanded the question to include the Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico.

“It’s kind of like a chicken-and-egg question,” she said of the Virgin Islands. “In a lot of ways people would say, ‘Well, you know, you’re really a small in terms of population, your economy has not grown in such a way that would allow you to seem like you’re mature enough to be a state.’ But are we that way because of the status that we’re in, because we are a colony, because we have not been given the support necessary to grow ourselves into being at a position where we can be states, right?

“You look at . . . from the Northwest Ordinance prior to that, every place that was considered a territory, the understanding was that eventually they would be a state. And the federal government gave such financial support and economic stimulus to those areas so that they would find themselves in a position to be a state, whether that’s bringing, you know, the Homestead Act, making it feasible for individuals to come there and farm or creating incentives for businesses to be there. . . .”

Plaskett also said, “Of course, we’re very interested in the District of Columbia being a state. I am actually for Puerto Rico statehood. And as the Virgin Islands in two years, we will be at our 175th year from emancipation of the U.S. Virgin Islands. The U.S. Virgin Islands and Haiti are the only two places in the Western Hemisphere that obtained their freedom from chattel slavery through organized, open rebellion, from violent overthrow.

“And so we count that date as very, very sacred to us. It’s July 3, interestingly, and so there’s been a question in our local legislature, myself and the governor, that we need to put that question out to our residents and to the people of the Virgin Islands, to determine if what they want our status to be moving forward.”

The delegate then panned her Zoom camera to the inviting blue waters surrounding St. John, prompting attendees to re-evaluate their vacation plans.

“You need to be beating it on down to one of the prettiest islands you’ll ever find,” said Fred Sweets, veteran photojournalist now with the St. Louis American.

The Roundtable began with introductions to Babee Garcia (pictured), board member and director of digital strategy and content for Military Veterans in Journalism, a group that just launched in 2019.

The Roundtable began with introductions to Babee Garcia (pictured), board member and director of digital strategy and content for Military Veterans in Journalism, a group that just launched in 2019.

“We are just trying to expand our community making sure that we are presenting opportunities for women, veterans who are interested in journalism, veterans of color, military spouses,” she said. The group’s material declares, “About 7.6 percent of Americans have served in the armed forces. Yet, just two percent of American media personnel are vets.”

In addition, we met Anthony D. Coley, one of several new African American officials at the Justice Department, who is in charge of public affairs. “There are a lot of issues that a lot of people care about. Criminal justice reform is at the top of the list. Civil rights matters of at the top of the list,” Coley said, offering to return with other Justice Department officials.

- Brakkton Booker, NPR: Stacey Plaskett Is 1st Nonvoting House Delegate To Argue An Impeachment Trial (Feb. 10)

- Roy Peter Clark, Poynter Institute: How to serve up a tasty ‘truth sandwich?’ (Aug. 18, 2020)

- Emily Cochrane, New York Times: How Joe Neguse and Stacey Plaskett Plan to Wield Their Influence After Impeachment (Feb. 15)

- DataJournalism.org: Verification Handbook: For Disinformation And Media Manipulation

- Stuart Emmrich, Vogue: Who Is Stacey Plaskett, the Breakout Star of the Senate Impeachment Trial? (Feb. 10)

- Abigail Higgins, Business Insider: The FBI used my journalism to charge a January 6 insurrectionist. I have complicated feelings about that.

- Michael Kranish, Karoun Demirjian and Devlin Barrett, Washington Post: Democrats demand investigation of whether Republicans in Congress aided Capitol rioters (Jan. 13)

- Online News Association: Election 2020: Combating Misinformation, Disinformation and Deepfakes (Sept. 30, 2020)

- Jay Rosen, PressThink: If you’re worried that journalists have learned nothing from the Trump years. (March 21)

- Rob Tornoe, Editor & Publisher: Journalists Battle the Misinformation Pandemic (March 8)

- Darragh Worland with Rebecca Aguilar, News Literacy Project: Is That a Fact? Who are journalism’s new gatekeepers? (audio)

[btnsx id=”5768″]

To subscribe at no cost, please send an email to journal-isms+subscribe@groups.io and say who you are.

Facebook users: “Like” “Richard Prince’s Journal-isms” on Facebook.

Follow Richard Prince on Twitter @princeeditor

Richard Prince’s Journal-isms originates from Washington. It began in print before most of us knew what the internet was, and it would like to be referred to as a “column.” Any views expressed in the column are those of the person or organization quoted and not those of any other entity. Send tips, comments and concerns to Richard Prince at journal-isms+owner@

View previous columns (after Feb. 13, 2016).

View previous columns (before Feb. 13, 2016)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2018 (Jan. 4, 2019)

- Book Notes: Is Taking a Knee Really All That? (Dec. 20, 2018)

- Book Notes: Challenging ’45’ and Proudly Telling the Story (Dec. 18, 2018)

- Book Notes: Get Down With the Legends! (Dec. 11, 2018)

- Journalist Richard Prince w/Joe Madison (Sirius XM, April 18, 2018) (podcast)

- Richard Prince (journalist) (Wikipedia entry)

- February 2018 Podcast: Richard “Dick” Prince on the need for newsroom diversity (Gabriel Greschler, Student Press Law Center, Feb. 26, 2018)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2017 — Where Will They Take Us in the Year Ahead?

- Book Notes: Best Sellers, Uncovered Treasures, Overlooked History (Dec. 19, 2017)

- An advocate for diversity in the media is still pressing for representation, (Courtland Milloy, Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2017)

- Morgan Global Journalism Review: Journal-isms Journeys On (Aug. 31, 2017)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2016

- Book Notes: 16 Writers Dish About ‘Chelle,’ the First Lady

- Book Notes: From Coretta to Barack, and in Search of the Godfather

- Journal-isms’ Richard Prince Wants Your Ideas (FishbowlDC, Feb. 26, 2016)

- “JOURNAL-ISMS” IS LATEST TO BEAR BRUNT OF INDUSTRY’S ECONOMIC WOES (Feb. 19, 2016)

- Richard Prince with Charlayne Hunter-Gault,“PBS NewsHour,” “What stagnant diversity means for America’s newsrooms” (Dec. 15, 2015)

- Book Notes: Journalists Follow Their Passions

- Book Notes: Journalists Who Rocked Their World

- Book Notes: Hands Up! Read This!

- Book Notes: New Cosby Bio Looks Like a Best-Seller

- Journo-diversity advocate turns attention to Ezra Klein project (Erik Wemple, Washington Post, March 5, 2014)

![]()

20 comments