Saga Touches on Today’s Hot-Button Issues

Homepage photo: Jeffrey Isaac Greenberg 19+ / Alamy Stock Photo

[btnsx id=”5768″]

Saga Touches on Today’s Hot-Button Issues

It would be difficult to find a subject that touches on so many hot-button issues this Black History Month than “The Last Slave Ship: The True Story of How Clotilda Was Found, Her Descendants, and an Extraordinary Reckoning.“

It’s a just-published book by journalist Ben Raines, who was fired by his own newspaper, already two-thirds gutted by layoffs. The paper let him go in a dispute over Raines’ pursuit of the last slave ship to bring enslaved Africans to the United States.

“In their speed to get control of the story, they lost any connection to it,” Raines told Journal-isms in a telephone interview.

Raines is a son of former New York Times Executive Editor Howell Raines. In pursuing his project, the younger Raines benefited from his training as a river guide, a sideline while being a reporter. He later found the Clotilda, buried in an alligator-filled swamp a mere 2½ miles from the newsroom of the Mobile (Ala.) Press-Register, the newspaper that fired him.

Once Raines thought he had found the ship. He reported so, with the appropriate hedging. When it turned out not to be the right ship, a descendant of the enslaved gave Raines a hug and sang a gospel song in his ear, “There’s a bright side somewhere/Don’t give up until you find it.” He didn’t.

This is a saga not only about slavery, but about environmental racism, state-sanctioned Jim Crow, relations between Africans and African Americans, reparations, politics in Africa, and the rewards of plain old grit and perseverance.

“The heroes of this story are the enslaved Africans who survived slaughter and bondage to build the first autonomous African-American community in America, beginning days after the end of slavery,” Raines writes.

The story is not over. Will the residents receive their just rewards after being victimized for more than a century?

Will the African space where they all originated — now the country of Benin — come to terms with its role in the slave trade?

There is competition to tell the story — a National Geographic project (video) premieres on Monday, based on a 2008 book by historian Natalie S. Robertson. A film co-produced by Ahmir ‘Questlove’ Thompson debuted two weeks ago at the Sundance Film Festival. “Everyone wanted a piece of the story and they were trying to get it any way they could,” Raines told Journal-isms.

Yet this is the kind of subject that would be banned in public schools, were a growing number of Republican-controlled Legislatures to call the tune.

The documented cruelty and dehumanization would make many “uncomfortable,” those legislators’ criterion for whitewashing America’s racial history under the false guise that it promotes “critical race theory.”

Still, in order to impart accurate information to the public, journalists themselves must be educated. An hour-long interview with Raines that aired on C-SPAN is a good introduction.

Ben Raines told his Facebook followers on Feb. 2, “C-Span had me on for an hour talking about The Last Slave Ship. It was the most expansive interview I’ve done related to Clotilda, and touches on the willful destruction of Africatown by city and state officials, what happened on the other side of the Atlantic during the era of enslavement, and how to honor the powerful legacy of the Clotilda captives. (Hint: dig up the ship and put it on display in a world class museum in Africatown.”

We can get some of the uncomfortable images out of the way. Warning: these passages are unquestioningly disturbing, stirring emotions over the Africans’ experiences and admiration for those who survived.

On the transatlantic voyage:

“Some of the slave ships of the era were carrying more than 1,000 people at a time, and it was just basically an attrition sort of thing,” Raines said on C-SPAN. “They kept them chained lying down, and many, many people would die on the crossing, but it was just the cost of doing business.

“With the Clotilda, because [ship captain William] Foster was invested — he was getting 10 of these people, but . . . they planned to get as many as 175 people, so they had a lot of food. They had extra food and more room in the hold. But these people were chained around the neck, naked, the neck chains were run through to the floor, and they were chained to the floor in groups of eight.”

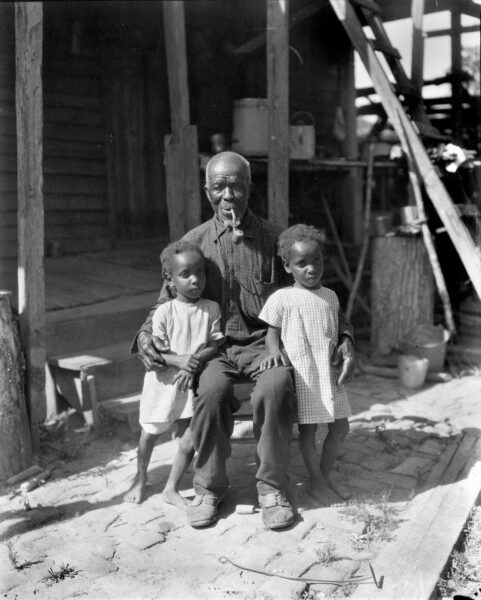

Raines refers to Cudjo Lewis, possibly the only captive able to describe life in Africa before being taken to America, the voyage through the Middle Passage, life during slavery and then in freedom. He arrived in 1860 and died in 1935 at about 94 years old. He told his story in 1927 to writer Zora Neale Hurston, recounting the raid on his village by Dahomean warriors, who killed his family members and kidnapped those later forced onto the Clotilda. “Barracoon,” Hurston’s account of those conversations, was considered so sensitive that it was not published until 2018. It is the only filmed record of Cudjo’s remembrances, as the New York Times has reported.

“It was I think 13 days before they were brought up from the hold and allowed to walk around on the deck,” Raines continued. “They weren’t able to walk when they first got up there. In the hold they just had to go to the bathroom wherever their peg was. So when a group got brought up on deck, they would be allowed — or forced — to scrub its little area during the crossing, and then another group would be brought up, so this went on for the whole trip. At one point Cudjo talks about something very chilling, but I have only seen one mention of in all the literature associated with everything about the Clotilda.

“He says that they were all brought up on deck, all the groups, and they were all chained to the anchor chain, by their neck chains . . . hooked to the anchor chain because the ship was being chased by another anti-slaving squadron ship. . . . so if they got caught they could cut the anchor loose and it would drag all the people — evidence — overboard.

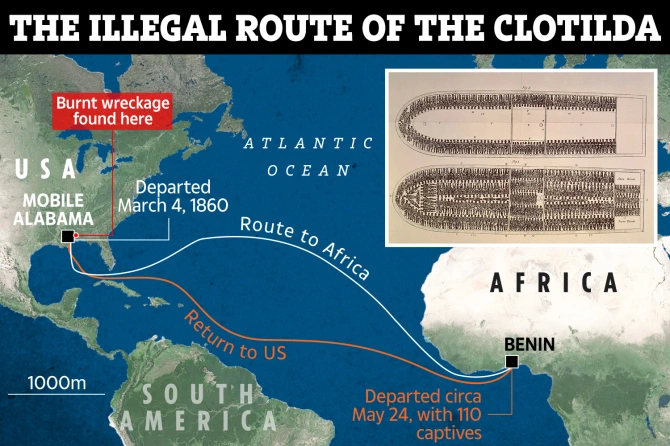

The Clotilda’s voyage was illegal because it proceeded despite an 1807 law making it illegal to import new slaves from Africa. Steamboat captain Timothy Meaher bet that his ship could make the trip anyway and took measures to disguise the Clotilda’s true intent. Later, Meaher and his confederates tried to burn the vessel to escape prosecution. The fire did not fully consume the ship, but burned enough for the owners to avoid punishment. (Credit: The Sun, Britain)

“And at one point in this journey, Cudjo describes being chained to the anchor chain with everyone else. I’m sure they didn’t know that they were about to be cast overboard, but that’s the kind of conditions they were in. Just horrific, at the edge of death every minute, hard to imagine. And by the time they were on the ship, it had been a month since they were captured. . . .

“At one point, he described that the Dahomans took the heads of everyone they killed as war trophies, and he describes seeing people he knew, their heads being smoked over a fire. So that’s what’s in his mind during the time he’s chained to the deck of this ship. It’s almost unbearable to think about the life of horrors that would leave you with.”

The Africans brought to Mobile showed remarkable cohesion, possibly because they all came from the same village. The anecdote is told of an overseer whipping a woman, prompting her to let out a shriek that brought the rest of the enslaved to her aid, attacking the overseer. “No one whipped an African [woman] after that,” Cudjo said.

Later, the Africans organized a community modeled after their villages in Dahomey, purchasing parcels from their villainous landowner.

As Raines continues, “Africa Town prospered from the 1900s forward early because it was a place apart from white Mobile, so all these businesses were big factories that came to town and those provided jobs. So that town grew and grew; by 1912 it was the fourth-biggest community in American governed by African Americans.

“By the 1950s and 1960s, more than 10,000 people were working the jobs, driving nice brick homes, everybody’s driving new cars . . . .”

Then came environmental racism of the kind that has victimized Black communities from Tulsa to St. Paul, Minn., and points east and west, north and south.

Authorities built a six-lane Interstate through the heart of the community, destroying buildings and businesses. “In 2000, the paper mills closed. And the International Paper Mill on the edge of Africatown was the largest paper mill in the world. So, in a heartbeat, thousands of the jobs were taken from the community as well because many people in Africatown worked there. Couple that with the crack epidemic, and Africatown was just left in shambles by the end of the 1990s. And there are fewer than 2,000 people there today and no businesses. The entire business district is gone.”

For years, the paper company spewed ash, soot and other material that contained dioxins and furans, known cancer-causing agents. Residents filed a class-action suit, settling in 2020 for paltry amounts.

Raines went to Benin, where he discovered a reckoning in progress over its role in the transatlantic slave trade.

Everybody there was part of that trade, either as slaver or enslaved.

Unlike in the West, African slavery was not passed down from generation to generation, and the enslaved were said to be considered part of the family. Africans used the term “deported” to describe those who were captured and sent away. “Slavery was something that happened once they reached America or Brazil,” said one official.

Still, the consequences were horrific and shameful, and slavery remains a point of contention between African Americans and Africans, as well as among citizens of Benin.

Raines wrote for the Mobile weekly Lagniappe, “I understood the concerns expressed by multiple government officials regarding how the country’s slaving past was portrayed.

“The creation of . . . new museums, and a push to attract tourists to the most important slavery sites means walking a fine line as the government simultaneously embraces the past and tries to assuage tribal resentments generations in the making. They fear, with some reason, that descendants of Dahomey’s victims might seek revenge in the modern age, and worry about promoting the darkest parts of the story.

“The fears are real. The Rwandan genocide of the 1990s was born of tribal resentments. The current chaos in Nigeria begins at the border, just 7 miles from Benin’s capital Porto Novo. Less than a week after I left Benin, the Islamist extremist group Boko Haram beheaded 13 kidnapped Christians in Nigeria. . . .”

Raines continued, “They are trying to have a national reconciliation. When you ride around Benin, there are monuments of people lost to slavery all over, and they are brutal. You’ll see a life-size person on a pedestal as you are driving down the road and that person is gagged, handcuffed and chained on their knees. It’s a lifelike statue in the heart of town. You will see walls where there are severed limbs all over them. Representing people lost to slavery. You’ll walk around and see statues with heads down and no face. And that’s meant to shame the living for their role in slavery.

“So I was stunned to find — here in America we are talking about reparations these days, and whether people who are descendants of enslaved people should be given something for the lives that were stolen from their ancestors. They are having that kind of conversation in Benin, too. And it’s exactly the same issue — slavery. The president of Benin was attacked in the last election because he has slave dealers in his family tree. You could see that wound is still there, in a way I have never understood or anticipated when I got there; it was quite remarkable.”

In Benin, Pastor Romain Zannou (pictured) recounted a visit to the United States in the early 1990s in which he detected a coolness that stemmed from the belief that Africans were to blame for selling American Blacks into slavery, Raines wrote in his book. “Zannou began apologizing to Americans for the actions of his forebears. He found that it opened a pathway to new friendships. He realized that the same sort of healing was needed within Benin, for descendants there on each side of the slavery divide.”

In Benin, Pastor Romain Zannou (pictured) recounted a visit to the United States in the early 1990s in which he detected a coolness that stemmed from the belief that Africans were to blame for selling American Blacks into slavery, Raines wrote in his book. “Zannou began apologizing to Americans for the actions of his forebears. He found that it opened a pathway to new friendships. He realized that the same sort of healing was needed within Benin, for descendants there on each side of the slavery divide.”

When African American pastors later went to a village in Benin, “They said, we have come to forgive you whose ancestors sold our ancestors. We can’t keep fighting among ourselves,” Zannou recounted. That forgiveness “opened the door for the two tribes to begin speaking to one another. Today, thirty years later, all of the children in the village attend school together, regardless of tribe, and the divide has disappeared.”

The film airs Feb. 7 on the National Geographic Channel at 10 p.m. EST, and starts streaming on Hulu and Disney+ the next day.

Reconciliation should also be a watchword on this side of the Atlantic. As the Guardian noted in reviewing Raines’ book, “In much the same terms as whites disdained them, African Americans ridiculed and ostracized the Clotilda captives and their offspring. They denounced them as ignorant, savage and ape-like. It’s little wonder their descendants came to lose the language of their ancestors and often to deny their heritage too.

In 2019, Michael Foster, whose great-great-great grandfather was the brother of the captain who led the Clotilda expedition, reached out to apologize to the descendants of the enslaved. Raines arranged the meeting. Foster’s trepidation was such that he removed his wedding ring “in case anyone wanted some kind of revenge against me for what my ancestor did.”

There was hugging, crying and forgiveness, Raines wrote.

Now the dreams are for the ship to be restored, put on display and to spark a boom in the economy along what is called the Civil Rights Trail, linking 110 landmarks in 14 states and Washington D.C. The Clotilda would be one of the trail’s attractions.

“That ship should be dug up and put on display in a world-class museum in Africatown,” Raines said on C-SPAN. “So, there were 20,000 ships in the slave trade; less than — 13 have been found, counting Clotilda. Most of them were ships that sank in ports. None of them were involved in the American slave trade.

“In the Smithsonian’s African American History Museum in Washington — fantastic museum — they have a piece of a slave ship on display, but it’s a South African ship that sank in port in Brazil. Never involved in the American trade, and the piece they have is about the size of a brick. Here we have an entire ship, the contents are still in it — the casks and everything that was on it. We need to dig the ship up and put it on display in a museum in Africatown, a world-class museum.

“The new lynching museum in Montgomery, Ala., has generated a billion-dollar impact on the local economy. Imagine having the last slave ship on display, when we have everything I spoke about with the legacy of the people. We know everything about all the families that came from it, the people who were on the ship, so imagine that museum.

“Meanwhile, as we’re unable to get . . . the state of Alabama to commit to digging it up, building it . . . [the] Smithsonian and the French government are building two new ships in Benin, $25 million apiece, to talk about that country’s slavery-era history. How on earth can Benin, one of the poorest countries in the world, have two $25 million museums, and Africatown, home to the people stolen from Benin with the last slave ship — how can we not have a museum there?”

Such a museum might also give a boost to Africatown and to African Americans around the country.

Historian Sylviane A. Diouf’s (pictured) 2007 book “Dreams of Africa in Alabama” was an inspiration for Raines’ exposition.

Historian Sylviane A. Diouf’s (pictured) 2007 book “Dreams of Africa in Alabama” was an inspiration for Raines’ exposition.

“There is a real urgency in preserving Africatown, not only for the people who are heirs to an exceptional part of African, African American and American history, but also for others. . . .,” Diouf wrote then. “Africatown descendants know for sure who their African ancestors were, from where they left, and when they arrived. They are the only ones with an African Town to call their own, and they are eager to share.”

As for Raines, he told C-SPAN, “As a journalist, what I want more than anything is to write something that changes people’s lives, that helps, and I don’t think I could ever come up with anything I could ever do again that would have the power and potential that this story has had.

“So I just want to get back out there and see what else we can find and what else we could do. And I guess the answer is, who knows?”

- Matthew Barakat, Associated Press: Committee controlled by Dems kills Youngkin education bills

- Molly Beck, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Evers vetoes bill that would have barred school lessons on systemic racism

- Darrin Bell cartoon, Washington Post

- Jamelle Bouie, New York Times: We Still Can’t See American Slavery for What It Was (Jan. 28)

- Hillary Chabot, Northeastern University: Why this journalist embraces critical race theory (Oct. 28)

- Dignity Justified: Clotilda and Africatown: Voices of the Clotilda: Africatown: Joycelyn Davis

- Charlotte Edwards, the Sun, U.K.: SHAME REMAINS Wreck of last slave ship that ferried 100s of captives from Africa to the US illegally found off Alabama coast (May 23, 2019)

- Lynn Elber, Associated Press: TV marks Black History Month with provocative, creative fare

- Mike Freeman, USA Today: ’28 Black Stories in 28 Days’ still needed two years after murder of George Floyd

- Peniel E. Joseph, CNN: Black History Month exposes the fallacy of White ‘discomfort’

- National Geographic: National Geographic Dives Into the Untold History of the Transatlantic Slave Trade with New Podcast, Into the Depths, Launching Jan. 27 (Jan. 13)

- NBCUniversal: NBCUniversal News Group Commemorates Black History With Cross-Platform Coverage Showcasing Black Heritage and Culture

- Ben Raines, Los Angeles Times: The Clotilda is the only American slave ship ever found. It needs to be preserved (July 17, 2019)

- Ben Raines with Mary Louise Kelly, NPR: The Clotilda, Last Known Ship To Bring Slaves To The U.S., Discovered In Alabama (May 23, 2019)

- Ben Raines, al.com: Wreck found by reporter may be last American slave ship, archaeologists say (Jan. 23, 2018, updated; Mar. 06, 2019)

- Ben Raines, Lagniappe Weekly: Benin and back again (Dec 31, 2019)

- Jay Reeves, Associated Press: Research: Wreck of last US slave ship mostly intact on Alabama coast (Dec. 22)

- A.E. Rooks, Daily Beast: Did You Study the Slave Trade in School or Were You Out That Day?

- Nichelle Smith, USA Today: In the crucible of historic change, I grew up Black and proud

- Michael Paul Williams, Richmond (Va.) Times-Dispatch: Gov. Youngkin’s “critical race theory” order is the epitome of systemic racism. Leave MLK out of it. (Jan. 18)

- Cleve R. Wootson Jr., Washington Post: Trump and allies try to redefine racism by casting White men as victims

[btnsx id=”5768″]

To subscribe at no cost, please send an email to journal-isms+subscribe@groups.io and say who you are.

Facebook users: “Like” “Richard Prince’s Journal-isms” on Facebook.

Follow Richard Prince on Twitter @princeeditor

Richard Prince’s Journal-isms originates from Washington. It began in print before most of us knew what the internet was, and it would like to be referred to as a “column.” Any views expressed in the column are those of the person or organization quoted and not those of any other entity. Send tips, comments and concerns to Richard Prince at journal-isms+owner@

View previous columns (after Feb. 13, 2016).

View previous columns (before Feb. 13, 2016)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2018 (Jan. 4, 2019)

- Book Notes: Is Taking a Knee Really All That? (Dec. 20, 2018)

- Book Notes: Challenging ’45’ and Proudly Telling the Story (Dec. 18, 2018)

- Book Notes: Get Down With the Legends! (Dec. 11, 2018)

- Journalist Richard Prince w/Joe Madison (Sirius XM, April 18, 2018) (podcast)

- Richard Prince (journalist) (Wikipedia entry)

- February 2018 Podcast: Richard “Dick” Prince on the need for newsroom diversity (Gabriel Greschler, Student Press Law Center, Feb. 26, 2018)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2017 — Where Will They Take Us in the Year Ahead?

- Book Notes: Best Sellers, Uncovered Treasures, Overlooked History (Dec. 19, 2017)

- An advocate for diversity in the media is still pressing for representation, (Courtland Milloy, Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2017)

- Morgan Global Journalism Review: Journal-isms Journeys On (Aug. 31, 2017)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2016

- Book Notes: 16 Writers Dish About ‘Chelle,’ the First Lady

- Book Notes: From Coretta to Barack, and in Search of the Godfather

- Journal-isms’ Richard Prince Wants Your Ideas (FishbowlDC, Feb. 26, 2016)

- “JOURNAL-ISMS” IS LATEST TO BEAR BRUNT OF INDUSTRY’S ECONOMIC WOES (Feb. 19, 2016)

- Richard Prince with Charlayne Hunter-Gault, “PBS NewsHour,” “What stagnant diversity means for America’s newsrooms” (Dec. 15, 2015)

- Book Notes: Journalists Follow Their Passions

- Book Notes: Journalists Who Rocked Their World

- Book Notes: Hands Up! Read This!

- Book Notes: New Cosby Bio Looks Like a Best-Seller

- Journo-diversity advocate turns attention to Ezra Klein project (Erik Wemple, Washington Post, March 5, 2014)

When you shop @AmazonSmile, Amazon will make a donation to Journal-Isms Inc. https://t.co/OFkE3Gu0eK

— Richard Prince (@princeeditor) March 16, 2018

6 comments