Blacks Portrayed as Victims; Whites as Saviors

‘Happy Talk’ on COVID Is More White Privilege, by Derrick Z. Jackson

“Come Hell or High Water: The Battle for Turkey Creek,” released in 2013, follows the painful but inspiring journey of Derrick Evans, a Boston teacher who moves home to coastal Mississippi when the graves of his ancestors are bulldozed to make way for the sprawling city of Gulfport.

Homepage photo: Derrick Evans, from “Come Hell or High Water: The Battle for Turkey Creek”

Photos by Sharon Farmer/sfphotoworks except where noted

Blacks Portrayed as Victims; Whites as Saviors

On the Mississippi Gulf Coast, a Black Boston schoolteacher named Derrick Evans helped residents fight back against the city of Gulfport’s 25-year plan for growth that would eviscerate the historically Black community of Turkey Creek. The graves of the residents’ ancestors — formerly enslaved people who settled on the Gulf Coast in the 1860s — had already been bulldozed to make way for what is now Gulfport.

In Spartanburg, S.C., State Rep. Harold Mitchell Jr., like Evans an African American, helped residents work with 124 partners to reverse the health impacts that industrial toxic wastes have had on the region. They worked to provide job training opportunities, establish six health care centers, construct more than 500 new affordable/workforce housing units, senior housing, a neighborhood park and an award-winning community center.

That initiative, known as the Spartanburg ReGenesis Project [PDF], developed reuse plans for formerly contaminated property that includes building a solar farm and an urban golf course.

Meanwhile, in Queens, N.Y., the Allen A.M.E. Church set up its own corporations that obtained government urban-blight funding to renovate housing and shops. Under its pastor, the Rev. Floyd Flake, it launched a kindergarten-though-grade 8 school, built a 300-unit senior housing complex, renovated entire dilapidated blocks of storefronts and is building two-family homes with state and city funds. The church employs 800 people and has helped inject $25 million in investment into the neighborhood. It also runs a Head Start program and a community health clinic.

These projects run counter to a popular narrative of Black people as victims whose rescue comes from white environmental activists and officials.

So said Mustafa Santiago Ali (pictured), formerly of the Hip-Hop Caucus and the Environmental Protection Agency, now vice president of environmental justice, climate and community revitalization at the National Wildlife Federation.

So said Mustafa Santiago Ali (pictured), formerly of the Hip-Hop Caucus and the Environmental Protection Agency, now vice president of environmental justice, climate and community revitalization at the National Wildlife Federation.

Ali spoke May 23 at the Zoom Journal-isms Roundtable.

The title, “Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology): How journalists can better cover environmental justice/environmental racism,” came from the Marvin Gaye song on the “What’s Going On” album, whose 50th anniversary is being commemorated this year.

Fifty people were on the Zoom, with 138 more on Facebook Live. The session may be viewed on YouTube.

Ali was joined by other environmental justice experts, some of them the very journalists who were on the call. And when the session neared its end, Charles Lee, senior policy adviser for environmental justice at the EPA, told the group, “I learned so much and was inspired by all that you do.”

A common thread surfaced throughout the two-hour conversation: that the media themselves were part of the environmental racism. Another was that news stories too often put environmental issues, like others, in a silo disconnected from other policy choices, such as where to locate freeways or high-rise housing.

Sadie Babits, board president for the Society of Environmental Journalists, said as much. “Journalists covering environmental injustice, public health and climate change must inform the public about how the systems in our society perpetuate inequities,” Babits told the group. “We also have a responsibility to examine our own industry and how racist structures affect our news choices, story framing, reporting and editing, as well as the treatment of our colleagues of color in their workplaces.”

An example of one policy consequence came from Heather McTeer Toney, climate justice liaison for the Environmental Defense Fund and the first African American and first female mayor of Greenville, Miss. This one came to mind as the nation commemorates the massacre of Black residents 100 years ago in Tulsa, Okla.

“Tulsa Greenwood district was rebuilt with an interstate on one side bordering a railway on the other side. So [it’s] quite literally the epitome of air pollution covering a Black community continuing into today’s society. Where and how are we talking about this? . . . Instead of putting it in the box, recognize that climate and environment [are] actually the table that all the boxes sit on.”

Media portrayals have repercussions, the speakers said. Toney explained, “When those donors read the stories, they are moved to take an action. But who writes the story and the way the story is written clearly determine how and where they put their money.”

Ali pointed to the stories’ effect on self-esteem. Report these issues “so that folks see that there is a North Star, and we are a part of that North Star,” Ali said.

Evlondo Cooper (pictured), senior writer with the climate and energy program at the media monitoring website Media Matters for America, added, “Good reporting can disrupt public apathy, frustration and cynicism about the efficacy of environmental action.

Evlondo Cooper (pictured), senior writer with the climate and energy program at the media monitoring website Media Matters for America, added, “Good reporting can disrupt public apathy, frustration and cynicism about the efficacy of environmental action.

“Too many groups that are doing substantive work improving the material conditions of their neighborhood and communities are laboring outside of the mainstream media spotlight. . . . Begin reporting on how environmental justice intersects with the lives of everyday people, and connecting environmental consequences to political and corporate policies and practices that lead to disproportionate and inequitable harm. . . . Amplify the voices of those on the frontlines of these fights.”

In May, Cooper led a Media Matters study that found that over the past four years, “11.4%, or 30 of 264, corporate broadcast morning and evening news segments included a mention of how . . . environmental pollution impacts, regulations, or health hazards specifically affected a particular demographic group.” However, “environmental pollution impacts were reported, but injustices were not.“

This century’s most well-reported environmental justice issue is the water contamination crisis that blew up seven years ago in Flint, Mich., so devastating that in January a federal judge ordered a $641 million settlement for residents.

The media fell short in covering that catastrophe, said Derrick Z. Jackson (pictured), a former Boston Globe columnist who in 2017 analyzed that coverage after becoming a Joan Shorenstein Fellow at Harvard University.

The media fell short in covering that catastrophe, said Derrick Z. Jackson (pictured), a former Boston Globe columnist who in 2017 analyzed that coverage after becoming a Joan Shorenstein Fellow at Harvard University.

“Number one, the media came late,” Jackson told us. “There was plenty of local media coverage of the Flint water crisis. But the national media, by coming late, they missed all of the protests by a more incredible multicultural world of people in Flint, including ex-offenders, who were part of the bottled water drives. . . .

“Second, by coming late and missing the agency of all the people of color, and that universe, then the coverage ended up focusing on the white heroes and the white saviors of the crisis. . . .

“So then that created a cycle . . . even though as I said, Black people were complaining, from ministers to ex-offenders to politicians, not a single African American, Black person was called a hero by the mainstream press. . . . You don’t have to wait for [a] quote [from] scientists who tend to be disproportionately white to validate the experience of people holding up bottles of orange and brown water.”

Perhaps no group can claim environmental injustice more than Native Americans. Dina Gilio-Whitaker (Colville Confederated Tribes) (pictured) is a lecturer of American Indian Studies at California State University San Marcos and author of “As Long as Grass Grows: The Indigenous Fight for Environmental Justice from Colonization to Standing Rock.” She said that for Native Americans, “the concept of environmental racism is not broad enough.

Perhaps no group can claim environmental injustice more than Native Americans. Dina Gilio-Whitaker (Colville Confederated Tribes) (pictured) is a lecturer of American Indian Studies at California State University San Marcos and author of “As Long as Grass Grows: The Indigenous Fight for Environmental Justice from Colonization to Standing Rock.” She said that for Native Americans, “the concept of environmental racism is not broad enough.

“In the book, I argue that environmental justice for American Indian people specifically is really different than it is for other E.J. [environmental justice] communities, to use that language that we use in this work. And the reason that it’s different is because for American Indian people, environmental injustice begins with genocide and land dispossession. It’s about the impulse of the state to erase, to literally eliminate indigenous people.

“And it does this in countless ways over history over 500 years. . . . ” The forced expulsion off lands, starvation into submission to impose treaties, forcing land concessions. “Those are just the beginning points for Native peoples.”

Gilio-Whitaker continued, “What we have today is a result of what I would call . . . industrial colonialism; all the kinds of impacts that Black communities face, that low-income communities face, other E.J. communities face are a result of this relationship of domination that Europeans had to the land and brought with them and, and forced the ending of indigenous land management practices that really constructed lives of . . . sustainability for 15,000-plus years.

“Journalists really need to educate themselves about that.”

Speakers saw the Biden administration in hopeful terms. “Inside of the stimulus bill that was

signed,” said Ali, “there was $100 million that was dedicated to environmental justice. Fifty million of that was supposed to go to monitoring, and then the other 50 million, you know, is going to be utilized in a number of different ways. So that’s the largest pot of money on the federal side of an equation in the 25-plus years that I’ve been doing this.”

The appointment of Deb Haaland, a Native American member of Congress, as secretary of the Interior “is a huge step. And and it’s a bold step,” said Gilio-Whitaker. “Anybody who knows anything about Deb Haaland [understands] her commitment to the environment and to having a clean and equitable environment for everybody, not just for Native people. . . . I totally trust her leadership in this, while I simultaneously recognize that, you know, she’s working for the federal government, and she’s working within structures whose logics are based on indigenous elimination.”

Representing EPA, Lee outlined steps the administration is taking: Foremost is “an all-of-government approach towards environmental justice,” including, in the words of an executive order, “a government-wide Justice40 Initiative with the goal of delivering 40 percent of the overall benefits of relevant federal investments to disadvantaged communities and [that] tracks performance toward that goal through the establishment of an Environmental Justice Scorecard.”

Of course, there is more to be done.

The biggest environmental groups, collectively known as “Big Green,” came in for their share of criticism. “It’s important for Big Green and other grassroots groups who have relationship with various media outlets to work with them to help them understand the broader concepts of environmental justice and Just Transition,” said Cooper.

“We cannot underestimate how disconnected they are from the everyday work going on across the country and how they lack a framework for understanding and contextualizing it and are, thus, unable to communicate it to their audiences.”

Ali called out philanthropic organizations. “Because if they had told these larger conservation and environmental organizations that you will work in an effective manner with frontline organizations, then that would have changed the dynamics.”

It is not a given that new environmental technologies will benefit people of color.

“Is there going to be Black and brown and indigenous ownership of the businesses that will be needed to be created around EVs [electric vehicles] and other types of electrical vehicle technologies?” asked Ali. “If we’re talking about making serious transformational change inside of our communities, all that has to come into the mix.”

Native protesters created this photo montage video from three months of protecting sacred land at Thacker Pass, Pee-hee-mm-huh, land of the Shoshone and Paiute people. In April, the Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribe formally resolved to cancel a Project Engagement Agreement with mining company Lithium Nevada, citing threats to land, water, wildlife, hunting and gathering areas and to sacred sites.

Electric cars run on batteries. Those batteries require lithium, Gilio-Whitaker noted.

“I don’t know how many people are paying attention to lithium mining, but this is something that’s looming on the horizon,” she said. “There is a lithium mine planned for Northern Nevada in the homelands of the Shoshone people,” who have registered their dissent, as have local ranching communities and environmental communities.

The quest for control of lithium is so ruthless it is said to have spurred a military coup in Bolivia two years ago.

Environmental justice is a global issue. The World Health Organization says that 24 percent of

all global deaths are linked to the environment, roughly 13.7 million deaths a year.

Toney (pictured) said, “I can assure you for every major company that is polluting in the United States, they’re doing the same thing in Nigeria, they’re doing the same thing off the coast of South Africa. They’re doing the same thing in places where human rights issues have been issues for years and are part of . . . our diaspora. So if we’re going to say that it’s not correct here, we have an obligation to hold corporations accountable across the globe. And if there’s anybody who can do that and do that well, I think it starts with us.”

Toney (pictured) said, “I can assure you for every major company that is polluting in the United States, they’re doing the same thing in Nigeria, they’re doing the same thing off the coast of South Africa. They’re doing the same thing in places where human rights issues have been issues for years and are part of . . . our diaspora. So if we’re going to say that it’s not correct here, we have an obligation to hold corporations accountable across the globe. And if there’s anybody who can do that and do that well, I think it starts with us.”

Fergus Shiel, managing editor of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, saw the need for more reporting. “What we have spent the past 15 years doing is uncovering who owns shell companies,” he said.

“And some of those shell companies, those many thousands of shell companies, are involved in some of the worst environmental disasters in many countries. And one of the the very minimum things that I think could be done is that, say, for example, the people in St. Croix, at the very least they should know who owns the company that is polluting their waters. That is the minimum. And unfortunately, in countries across the world, people can’t even find out who the polluters are. And that’s what I see changes.”

Are there enough of the “us” that Toney mentioned to go around?

Rebecca Aguilar, president-elect of the Society of Professional Journalists, said, “Yes, journalists haven’t done enough on the environment. And I think sometimes the journalists of color are so busy trying to tell all the other stories about the communities that sometimes the environment falls to the bottom unless there is some kind of pollution or, you know, contaminated water issue affecting our communities.”

Gloria Gonzalez, deputy energy editor of Politico, agreed. “It’s something that I’ve struggled with, as a journalist covering these issues for 20-plus years. . . . We’re stretched too thinly, right? There’s too many, there’s so many important stories that we have to tell, we want to tell and not enough time, not enough resources. . . . . So maybe there’s a way we can all work together to share that type of information and get those stories out there.”

Especially getting the stories to the common man, said Rochelle Riley, former Detroit Free Press columnist now working for the city of Detroit.

She promised to connect with Denise Rolark Barnes, publisher of The Washington Informer. “I think that may be something the Black press can do. I’m talking something that’s like a weekly feature or something where you have a regular look at what people are writing about that affects people’s lives. . . . It’s a necessity.”

It’s on the agenda at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University, the incoming dean, Dr. Battinto Batts Jr., told us as we congratulated him. “We’re preparing the students to go out into communities and go into their careers with an awareness of what the issues are. And . . . this is something that I’m very interested in,” he said. Cronkite always wants to be “at the forefront of journalism and journalism education.”

More good news: “The Uproot Project, a collective network of and for environmental journalists of color that’s launching this month,” Hanaa’ Tameez reported in March for Nieman Lab. “The Uproot Project is dedicated to advancing the careers of journalists who have been historically underrepresented in environmental and science journalism and can offer the industry fresh perspectives.“

- Audubon Naturalist Society: 2021 Taking Nature Black conference

- Stacy M. Brown, National Newspaper Publishers Association: Environmental Racism is Real, Destructive and Deadly (May 18)

- Cathy Bussewitz, Associated Press: Biden pushes for diversity in transition to clean energy (May 4)

- Drew Costley, Associated Press: People of color more exposed than whites to air pollution (April 29)

- Earthjustice: Environmental Justice Advocates and National Environmental Groups Release Recommendations for Implementing President Biden’s Justice40 Commitment (March 17)

- Hazel Trice Edney, thedrumnewspaper.com: Environmental racism grows as environmental groups turn increasingly white (April 27, 2019)

- Darryl Fears, Washington Post: The racist legacy many birds carry

- Journal-isms: Climate Change Called Issue of Equal Justice (Oct. 11, 2018)

- Maya L. Kapoor, High Country News: Nevada lithium mine kicks off a new era of Western extraction (Feb. 18)

- Yanick Rice Lamb, Center for Public Integrity: ‘Unintended Consequences: The Rubber Industry’s Toxic Legacy in Akron (March 5)

- National Marine Sanctuary Foundation: The next Capitol Hill Ocean Week will be June 8-10, 2021 and focus on justice, equity diversity, and inclusion in the ocean and Great Lakes community.

- Nadja Popovich, Josh Williams and Denise Lu, New York Times: Can Removing Highways Fix America’s Cities?

- National Press Foundation: Apply: Environmental Justice Grants

- Erik Ortiz, NBC News: ‘The numbers don’t lie’: The green movement remains overwhelmingly white, report finds (Jan. 13)

- Jesse Remedios, ncronline.org: Environmental scientist roots work in sanctity of life: A conversation with Sylvia Hood Washington (July 21, 2020)

- Shantella Y. Sherman, Washington Informer: Remembering Damu Smith, Environmental Warrior (April 21)

- The Solutions Project: Covering Climate Equitably: A Guide for Journalists [PDF]

- Heather McTeer Toney, Dame magazine: It’s High Time We Listen to Indigenous Women on Climate (May 18)

- David Treuer, the Atlantic: Return the National Parks to the Tribes (May 2021 issue)

- Washington Informer: 2021 Sustainability Supplement in Observance of Earth Day (April 21)

- Elizabeth Williamson, New York Times: The Promise and Pressures of Deb Haaland, the First Native American Cabinet Secretary

‘Happy Talk’ on COVID Is More White Privilege

By Derrick Z. Jackson

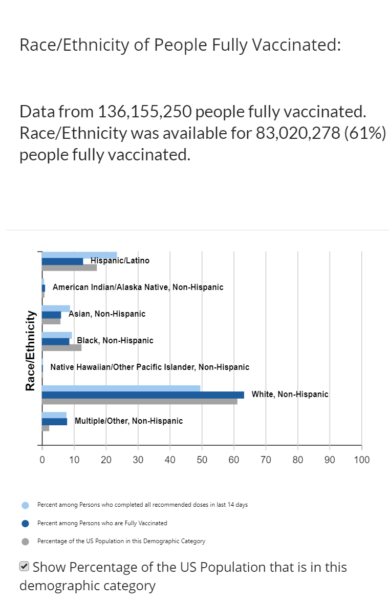

The failed coverage of the national media in the Flint water crisis still haunted the media’s reporting on COVID. Most recently, we’ve been hearing the march toward what is currently 60 percent of the population having received one vaccine dose and 48 percent fully vaccinated. But rarely do the national media add what should be an obligatory critical additional paragraph explicitly saying that only white people are being vaccinated at or above their share of state populations in virtually every state.

Black and brown people remain undervaccinated compared with their share of state populations in most states, according to May 17 data maintained by the Kaiser Family Foundation. The disparities remain dramatic for Black people in states like Pennsylvania, Delaware, Florida and New Jersey as well as in Washington, D.C. Yawning disparities for Latinx are in states such as California, Colorado, New Jersey and Arizona. In most cases, we’re not talking about pint-sized states.

In the CDC’s latest data posted May 23, white people, 61.2 percent of the population, make up 64 percent of those fully vaccinated.

In the CDC’s latest data posted May 23, white people, 61.2 percent of the population, make up 64 percent of those fully vaccinated.

Meanwhile Black people, 12.4 percent of the population, are only 8.6 percent of those fully vaccinated. Latinx, 17.2 percent of the population, make up only 12.3 percent of the fully vaccinated.

This means that the massive “reopening” of economies and the happy talk from mayors, governors and even the Biden administration about no longer needing masks if one is fully vaccinated, is a blatant form of white privilege.

But the national media are only covering the topline generality of who is vaccinated, which renders Black and brown people invisible to the same kind of policy decisions that put them disproportionately at risk at the beginning of the pandemic and now leaves them more at risk in what White leaders consider the homestretch.

This as conservative governors are en masse ending COVID unemployment benefits when we know that Black and brown people disproportionately are “essential workers” or otherwise dominate the cheap labor force.

Derrick Z. Jackson is a fellow at the Union of Concerned Scientists. He writes for grist.org and The Undefeated, is on the board of Environmental Health News and is an adviser to Inside Climate News. He is a former Boston Globe columnist.

- Roger Caldwell, National Newspaper Publishers Association: COMMENTARY: Blacks in Florida Lag Behind Every Community in Getting Vaccinated

To subscribe at no cost, please send an email to journal-isms+subscribe@groups.io and say who you are.

Facebook users: “Like” “Richard Prince’s Journal-isms” on Facebook.

Follow Richard Prince on Twitter @princeeditor

Richard Prince’s Journal-isms originates from Washington. It began in print before most of us knew what the internet was, and it would like to be referred to as a “column.” Any views expressed in the column are those of the person or organization quoted and not those of any other entity. Send tips, comments and concerns to Richard Prince at journal-isms+owner@

View previous columns (after Feb. 13, 2016).

View previous columns (before Feb. 13, 2016)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2018 (Jan. 4, 2019)

- Book Notes: Is Taking a Knee Really All That? (Dec. 20, 2018)

- Book Notes: Challenging ’45’ and Proudly Telling the Story (Dec. 18, 2018)

- Book Notes: Get Down With the Legends! (Dec. 11, 2018)

- Journalist Richard Prince w/Joe Madison (Sirius XM, April 18, 2018) (podcast)

- Richard Prince (journalist) (Wikipedia entry)

- February 2018 Podcast: Richard “Dick” Prince on the need for newsroom diversity (Gabriel Greschler, Student Press Law Center, Feb. 26, 2018)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2017 — Where Will They Take Us in the Year Ahead?

- Book Notes: Best Sellers, Uncovered Treasures, Overlooked History (Dec. 19, 2017)

- An advocate for diversity in the media is still pressing for representation, (Courtland Milloy, Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2017)

- Morgan Global Journalism Review: Journal-isms Journeys On (Aug. 31, 2017)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2016

- Book Notes: 16 Writers Dish About ‘Chelle,’ the First Lady

- Book Notes: From Coretta to Barack, and in Search of the Godfather

- Journal-isms’ Richard Prince Wants Your Ideas (FishbowlDC, Feb. 26, 2016)

- “JOURNAL-ISMS” IS LATEST TO BEAR BRUNT OF INDUSTRY’S ECONOMIC WOES (Feb. 19, 2016)

- Richard Prince with Charlayne Hunter-Gault,“PBS NewsHour,” “What stagnant diversity means for America’s newsrooms” (Dec. 15, 2015)

- Book Notes: Journalists Follow Their Passions

- Book Notes: Journalists Who Rocked Their World

- Book Notes: Hands Up! Read This!

- Book Notes: New Cosby Bio Looks Like a Best-Seller

- Journo-diversity advocate turns attention to Ezra Klein project (Erik Wemple, Washington Post, March 5, 2014)