NABJ, Others Urged to Step Up to the Plate

Poster for “Press Freedom in Black-Run Countries” (Please click to view)

Homepage photo: In May, the UNCAC Coalition, an Austria-based network of more than 400 civil society organizations worldwide, expresses concern regarding a judicial decision by Somali authorities to freeze the bank accounts of the Somali Journalists Syndicate media freedom organization.

[btnsx id=”5768″]

Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken meets with Godfrey Otunge, commander of the Multinational Security Support Mission, and Normil Rameau, director of the Haitian National Police, at Toussaint Louverture International Airport in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, on Thursday. (Credit: Chuck Kennedy/State Department)

NABJ, Others Urged to Step Up to the Plate

This was one of the stories told by Jacqueline Charles of the Miami Herald (pictured), who covers the Caribbean, particularly Haiti, as she sat near Roberson Alphonse, a Haitian journalist who survived an assassination attempt and is now in the United States:

This was one of the stories told by Jacqueline Charles of the Miami Herald (pictured), who covers the Caribbean, particularly Haiti, as she sat near Roberson Alphonse, a Haitian journalist who survived an assassination attempt and is now in the United States:

Referring to Alphonse, who was being honored by the National Association of Black Journalists, Charles said, “There were other journalists that don’t have the visa, the friendships, the access, and they’re left alone” to fend for themselves.

“There’s a young man who had fled to the Dominican Republic. He has been jailed repeatedly. I’ve tried. I’ve helped. I would say, thank goodness the Dominican foreign minister stepped in at one point to assist! But he’s been [continually] subject to being pulled off the street. I tried to reach out to a particular journalism protection organization to assist him, and he didn’t have that. I went up to someone in Miami who works in this area, Latin America, and say, ‘Hey, we have a lot of journalists, Haitian journalists who are on the run, who have had to flee.’

“They’re coming here in Miami. Could we do something similar to what they’ve done in France? Sort of online where they’re still connected, they still have their sources. They’re still interested. It’s what they know, it’s what their profession is. Can we do something to help them to make a living, to continue with their profession?

“And they weren’t interested.”

Charles, twice chosen NABJ’s Journalist of the Year, in 2011 and 2022, was part of an Aug. 1 Journal-isms Roundtable on “Press Freedom in Black-Run Countries” held in Chicago at the same time as the NABJ convention, though not a part of it.

The session was labeled by Melvin Foote, founder of the Constituency for Africa and an attendee, as “somewhat historic.” Added press-freedom advocate Mohamed Keita, formerly with the Committee to Protect Journalists, now with the Human Rights Foundation, “One of the biggest problems in the U.S. media is parochialism.”

Jamaica’s Zahra Burton (pictured) said of the press-freedom topic, “I’m glad we’re highlighting it in Black-run countries, because that’s not necessarily a debate that’s usually had.” As has been said in this space, discussions of press freedom don’t usually involve Black-run countries, and discussions of Black-run countries don’t usually involve press freedom.

Jamaica’s Zahra Burton (pictured) said of the press-freedom topic, “I’m glad we’re highlighting it in Black-run countries, because that’s not necessarily a debate that’s usually had.” As has been said in this space, discussions of press freedom don’t usually involve Black-run countries, and discussions of Black-run countries don’t usually involve press freedom.

Charles’ story of the Haitian journalist who fled to Haiti’s neighboring country touched on a number of themes that resonated through the information-rich, sometimes heartbreaking Roundtable:

- The number of journalists in exile is growing. Exact figures are difficult to determine, but in August the Inter American Press Association awarded its highest distinction, the Grand Prize for Press Freedom, to “Journalism in Exile. This award honors colleagues and media outlets that have increasingly been forced to internally displace or migrate to other countries due to violence, threats, and persecution by criminal groups, corrupt officials, and authoritarian governments,” it said.

- Because it’s so often taken for granted in the United States, even journalists don’t fully realize the importance of a free press, it appeared.

Many of those fleeing are Black. Attendee Nichelle Smith (pictured), formerly an editor at USA Today, said afterward, “As immigration from the continent and the Caribbean continues to diversify what it means to be African American, it’s critical that we all learn each others’ full stories and share each others’ joy and pain. Our colleagues do incredibly important work under circumstances we can’t imagine. This powerful, eye-opening conversation and what we can do to help our brothers and sisters under fire should be a part of every major NABJ discussion going forward.”

Many of those fleeing are Black. Attendee Nichelle Smith (pictured), formerly an editor at USA Today, said afterward, “As immigration from the continent and the Caribbean continues to diversify what it means to be African American, it’s critical that we all learn each others’ full stories and share each others’ joy and pain. Our colleagues do incredibly important work under circumstances we can’t imagine. This powerful, eye-opening conversation and what we can do to help our brothers and sisters under fire should be a part of every major NABJ discussion going forward.”

- Resources to help these journalists are inadequate. Organizations that might be expected to step up to the plate, including NABJ itself, are not.

Citing the large number of proposals, NABJ rejected the idea for this discussion as a topic for its convention, which drew more than 4,000 attendees and ended generously in the black but barely mentioned the issue of press freedom. Yet the Roundtable panelists offered a range of remedies, some of which involved journalism organizations such as NABJ.

We live in an interconnected world, Muthoki Mumo (pictured), Africa program coordinator for Committee to Protect Journalists, based in Nairobi, Kenya, told the group. “If you look at U.N. data, by 2050 a significant part of the global population will be living in Africa, will be a youthful population,” she said. “This will have profound and grave impacts on global politics, on things like climate change. So we must ask ourselves, in what conditions is that youthful, increasingly powerful population, living? How are they informed? Are they informed by an independent press? Are they informed by an oppressed press? This will have grave and broad impacts beyond Black-run countries and on the global population as we move into this century.”

We live in an interconnected world, Muthoki Mumo (pictured), Africa program coordinator for Committee to Protect Journalists, based in Nairobi, Kenya, told the group. “If you look at U.N. data, by 2050 a significant part of the global population will be living in Africa, will be a youthful population,” she said. “This will have profound and grave impacts on global politics, on things like climate change. So we must ask ourselves, in what conditions is that youthful, increasingly powerful population, living? How are they informed? Are they informed by an independent press? Are they informed by an oppressed press? This will have grave and broad impacts beyond Black-run countries and on the global population as we move into this century.”

(Journal-isms Roundtable starts at 9:00)

The Journal-isms Roundtable was held at the home of Chicago Public Media, which produces the Chicago Sun-Times and WBEZ and commands a magnificent view of the Chicago River. NABJ’s Global Journalism Task Force was the co-sponsor.

Twenty-two people were in the room; 30 more were on the Zoom call, and 87 had watched the YouTube video by Sept. 6. The video is embedded above.

From left, Garry Pierre-Pierre, Roberson Alphonse and John Yearwood at the Journal-isms Roundtable’s first session outside the Washington area. (Credit: Deborah Barfield Berry)

The panelists were:

- Roberson Alphonse, Haitian exile and this year’s recipient of NABJ’s Percy Qoboza Award to a foreign journalist.

- Zahra Burton, 18 Degrees North, Jamaica; Global Reporters for the Caribbean — founder and principal, Kingston, Jamaica

- Jacqueline Charles, Haiti/Caribbean correspondent, Miami Herald

- Muthoki Mumo, Committee to Protect Journalists — Africa program coordinator, based in Nairobi, Kenya

- Garry Pierre-Pierre, Haitian Times — founder and publisher, Brooklyn, N.Y.

Nompilo Simanje (pictured), International Press Institute — Africa advocacy and partnerships lead, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

Nompilo Simanje (pictured), International Press Institute — Africa advocacy and partnerships lead, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

- John Yearwood, Politico – editorial director — diversity and culture

This columnist was moderator.

A major takeaway: the lack of a free press has implications many had not considered, and that shortcoming takes many forms.

Pierre-Pierre said Haitian authorities “know that they can put the fear of God in the journalists. . . . I mean, we joke a lot that we don’t make any money, but in Haiti they really don’t make any money.

“And so they become susceptible to corruption. Because, hey, I’m lucky to be here, to have a family —

But if I were in Haiti. I don’t know. . . . how ethical I would have been.”

Alphonse, who arrived in the United States still wounded, estimated that around 5 million Haitians, including journalists, are food insecure, earning less than $300 a month.

“We did deep-dive journalism to help protect press freedom. We don’t need fast-food journalism, people running around, you know, getting a bunch of cliches and write something. For me it’s insulting. You need to dive deep. You need to put context. You need to help raise the voice of our communities.”

Simanje of the International Press Institute cited “the role that the media plays as an enabler for other fundamental rights, and particularly access to information, which is quite critical to help us, you know, across the board . . . with regard to . . . political rights, socioeconomic rights.”

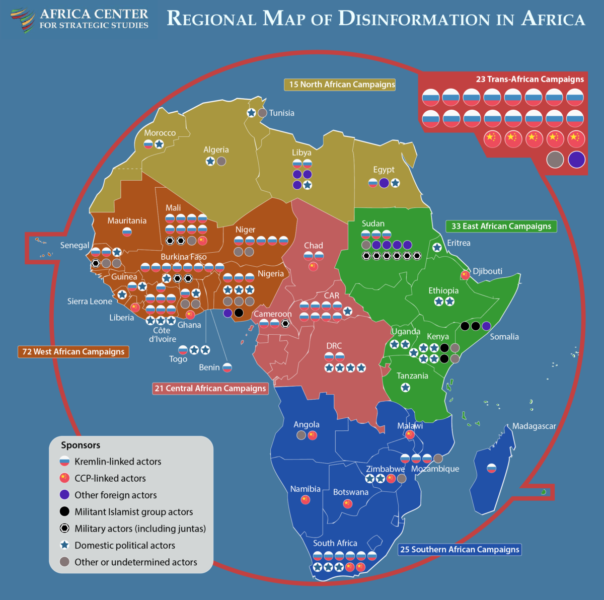

Outside actors such as China are among those spreading disinformation in Africa. See “Outsiders, Leaders Stoke Africa’s Media Crises“ (scroll down) (Credit: African Center for Strategic Studies)

Kenneth Cooper, a onetime correspondent in India for The Washington Post, recalled being asked by the State Department to help train African journalists in investigative techniques. “I was astonished to learn from them then, [that] in Sierra Leone, truth is not a defense in a libel lawsuit,” Cooper said.

In Uganda, feminist Stella Nyanzi was jailed after criticizing the country’s president for failing to deliver on his promise to give sanitary pads to all school-aged girls in the country to help female education rates.

Last year, Zimbabwe enacted an amendment to its criminal law code inspired by the U.S. Logan Act, “making it a criminal offense to be engaging in meetings with foreign agents,” something “that can be interpreted broadly to mean anything,” said Simanje. “What that means for journalism and generally human rights also is that it’s becoming even more difficult to speak up.” The U.N. High Commission for Human Rights is among those condemning the law.

Even in Jamaica, which ranks highest among Black-run countries on Reporters Without Borders’ press-freedom index (24, down from 7), some journalists practice self-censorship, Burton said.

“I can tell you that just this week I was speaking to a Ph.D student who’s doing his Ph.D In the U.K. But as a Jamaican journalist, and he was here and just hanging out for a few months to do some research, . . . he said he’s been speaking to different journalists in different mainstream media, and the complaint or the fear among those journalists is that if they do the kind of work that let us say I do at 18 Degrees North, which is more on the investigative journalism side, that they’ll ruffle feathers. They will be an outcast. They won’t have the access that they have to individuals in power now.”

Burton continued, “When I had asked a certain question that was very controversial in Jamaica, I was told by one person that he was actually called by somebody to track my vehicle . . . and do a profile on me . . . — he [declined] the job, declined to do it. He said he only does that for criminals.

“That’s the line of work he was in, and not for journalists like myself, and he and I just happened to know each other. And so he told me that.”

Still, said Yearwood, a former world editor at the Miami Herald, there is a hunger for the truth.

“I remember some years ago, when I served as chair of the International Press Institute, I was asked to go to Zambia on an emergency meeting, because the then-President Edgar Chagwa Lungu . . . decided one day to just shut the newspaper down. Put the chains on the door. Throw out all the reporters . . .

“And what they did was just sort of astonishing.

“They said. ‘If you close the building, then we’ll work on the sidewalks.’

“So when I arrived in Zambia.

“There were most of the reporters, with their desks, and their computers on the sidewalk. Turned that into a newsroom.

“And they were printing the newspaper probably through the [help] of a friend. And I was there one day when the newspaper arrived about 1 in the afternoon, and the lines of cars [were] so long. . . people were still coming to get the news despite what Edgar tried to do.”

Recommendations for solutions ranged from what journalism organizations, fellowship programs, government agencies and individual journalists can do, to Americans using the power of their votes in November.

Lynette Clemetson (pictured), who directs the Wallace House Center for Journalists at the University of Michigan, mentioned NABJ, as did Charles.

Lynette Clemetson (pictured), who directs the Wallace House Center for Journalists at the University of Michigan, mentioned NABJ, as did Charles.

“I was thinking, like, you know, why are we not at the conference where it’s like a standing room — standing room crowd?” asked Charles.

“Because these are, you know, important issues. And you know, for years we’ve talked about having already interconnectivity between Black journalists in the United States and Black journalists in the Caribbean and on the African continent.

“So I think that that is more and more important. I mean my first trip to Africa was through an NABJ program. But I think that it definitely stands to take the leadership in this and to do more on this, because [we need] to realize that it’s not just a firing squad [that’s] coming at you as a journalist, but that they’re finding other ways” to stifle press freedom.

Charles cited a precedent: “After the 2010 earthquake, NABJ supported Haitian journalists by gathering laptops. And John Yearwood is here and he actually led that charge. And I remember him putting those laptops in his suitcase. So we don’t get slapped with, you know, Customs issues and things. But one of the things that keeps coming up is that it has been a patchwork. It’s been a patchwork to support journalists on the ground. We need help.”

Charles proposed a fund to help those journalists. “This is an organization co-founded by one of my favorite professors, was the reason why I’m in journalism, the late Chuck Stone,” she said of NABJ. “And I think that today, you know, we need to take it to the next level. And that level is putting our money where our mouths are.”

Clemetson provided a safe haven for Alphonse at Wallace House and noted NABJ’s presentation to him of its Qoboza Award for a foreign journalist.

“I work with journalists like Roberson, who are literally trying to write with their hands in bandages, and I think sometimes journalists don’t realize, even in the face of, of course, all of the pressures that we have here [that] being asked to go back to your office and work in person is like not a real hardship compared to being shot at. . . .

“When we are adding support, we need to add our voices, we need to add actual resources, meaning financial support and organizations,” Clemetson said.

“That organizations. . . realize the full suite of things that it takes to get people back on their feet.

“I mean, we’re tremendously proud of Roberson for receiving the prize this year. But I will say, you know, for NABJ, when you give [an award to] a journalist in exile, you should be ready to cover their conference fees, and to make sure they can come to the conference . . .

“It is one thing to stand in the room and applaud someone, and that show of emotional support as a group is important.

“But there are many, many, many concrete things that people need over the long term,” therapy being one of them.

Clemetson went on to say the way the current fellowship programs are organized is “somewhat out of date. They were really designed for a different time in journalism, when people could come for one year, and the expectation is that at the end of the academic year the person is going back to a safe, full-time job at a news organization in the United States or in another country.”

In the United States, “people don’t have a lot of job security,” and the model certainly doesn’t work for a situation of exile.

“So we have to build more bridges between organizations, not see ourselves as competitors, but see ourselves as in collaboration with one another.

“Talking about, ‘OK, I can help for this period of time. And then who can step in to help after that?

“I worked with a colleague at Missouri and Roberson and Natalie,” his wife, “went and spent time as Friendly fellows at the University of Missouri.

“So it’s just a a complex patchwork of support.”

The New Humanitarian asks about the benefits of sending Kenyan police to Haiti. (Credit: YouTube)

Individual journalists must do more to escape the silos into which they sometimes view their work, the panelists said. Do those writing about Kenyan police being posted to Haiti also write about the accusations of abuses by Kenyan police at home and wonder whether the Kenyans are appropriate? Are foreign leaders asked about their own human rights records when they travel abroad, especially since that’s where many send their children?

Do journalism students at historically Black colleges and universities learn about press freedom issues in Black-run countries? Are American publications willing to publish stories that wouldn’t see the light of day in the home countries of many journalists in Africa or the Caribbean?

Another: Are NBA writers aware of the ESPN reports that described how the basketball association built a relationship with Rwandan dictator Paul Kagame “that, on the one hand, was central to launching its first league outside of North America, the Basketball Africa League, but, on the other, forced the NBA to look past persistent human rights abuses far worse than those it opposes at home.”

Some of the solutions, the panelists said, rest with government policies.

From Jamaica, Burton, an investigative reporter, praised the USAID Reporters Shield program, which, it says, “defends investigative reporting around the world from legal threats meant to silence critical voices.”

Clemetson urged a U.S. adaptation of a Canadian program that provides emergency visas for journalists [PDF].

But she said a major obstacle to journalists seeking asylum is the U.S. immigration system, which can keep a threatened journalist in limbo for years.

Clemetson and the National Press Club have each taken up this cause for embattled journalists. But three days after the Roundtable, veteran crime reporter Alejandro Martinez Noguez was killed in Mexico. It exposed a fallacy in one argument underpinning the U.S. immigration system, the press club said.

“Mexico’s government protection program is cited in asylum cases by the U.S. Government as a reason to deport Mexican journalists, who, the government argues in court, will be protected by Mexico,” the club said in a statement. “Sadly this program has proven over the years to be fatally ineffective.”

Should the U.S. government make press freedom a precondition for foreign aid? The State Department dodged such a question from Journal-isms, but Charles A. Ray (pictured, by Sharon Farmer), a retired ambassador who appeared at a previous Roundtable, “How U.S. Ambassadors of Color See the World,” responded.

Should the U.S. government make press freedom a precondition for foreign aid? The State Department dodged such a question from Journal-isms, but Charles A. Ray (pictured, by Sharon Farmer), a retired ambassador who appeared at a previous Roundtable, “How U.S. Ambassadors of Color See the World,” responded.

“It is [a precondition] in some cases, but like we used to say in the Army, it depends. We provide certain types of aid to countries where press freedom is restricted depending on other strategic security priorities. As you’re probably aware, until the coup and the junta expelling the US military from Niger, we had a drone base there and were providing some military training and assistance to the military. I don’t have the level of contact to give a detailed answer of current policy, but during my 30-year career that’s the way it worked, regardless of the administration in office.”

That brings us to the 2024 presidential election.

It was in 2016, during the Obama administration, Burton said, that the U.S. Embassy in Jamaica inquired about her well-being after hearing that she had received death threats when one of her stories about the prime minister generated controversy.

It was in 2018, during the Trump administration, that the president described Haiti and some African nations as “shithole countries.”

“I traveled in Africa quite a bit during the Trump administration, and spoke to ambassadors throughout the Continent, dealing with the issue of press freedom,” Yearwood said. “And one thing they told me time and time again.

“It’s almost impossible, very difficult, to do their job in terms of the press freedom issue when back home, they don’t have an ally, whether it’s the State Department or with the president. Saying things like what you talked about (‘”shithole countries”) the president saying makes their job exceedingly difficult.

“I mean, certainly with the Biden administration, it’s certainly a different time, different conversation. And then one of the things that we saw with the Biden administration is that they gave about a million dollars to a press freedom organization in Africa, to work on these issues.

“So that’s that’s the big difference. And no doubt there is, I’m sure, a lot of . . . deep concern

in different parts of the continent as you look at our presidential election.”

- AllAfrica: Mozambique: Of Angoche Accused of Attacking Journalists

- Juhakenson Blaise, Haitian Times: US Sec. of State Blinken pledges $45M in aid to gang-ravaged Haiti

- Committee to Protect Journalists: CPJ, partners call for release of slain Nigerian journalist’s body

- Daily Observer, Liberia: Publishers Take Stand Against Gov’t’s Overdue Debt to Media (Aug. 29)

- International Federation of Journalists: Guinea Bissau: Journalist union President denied the right to cover government activities

- Davidson Iriekpen, This Day, Nigeria: Ending Orgy of Journalists’ Arrests

- Fungi Kwaramba, the Herald, Zimbabwe: President Throws Media a Challenge ‘. . . Promote National Interests‘

- Ann Marie Lipinski, Nieman Reports: Evan Gershkovich and Alsu Kurmasheva Are Free. They’re the Exceptions

- Media Foundation of West Africa: MFWA, ECOWAS hold strategic meeting to strengthen media and democracy in West Africa

- Widlore Mérancourt and Amanda Coletta, Washington Post: As Haitians flee the capital, fears rise that the gangs will follow

- NY Carib News: Haiti – State of Emergency to Cover Entire Nation

- Shadrack Omuka, New Internationalist: Kenyan police target journalists covering anti-government protests

- Reporters Without Borders: USA: RSF urges both presidential campaigns to commit to strengthening press freedom (Aug. 16)

- Reporters Without Borders: In the past decade, 19 journalists have fallen victim to enforced disappearance worldwide – and remain missing

- Eric Schmitt, New York Times: Military Says Law Barring U.S. Aid to Rights Violators Hurts Training Mission (June 20, 2013)

- A.G. Sulzberger, Washington Post: How the quiet war against press freedom could come to America

- Namukabo Werungah, New Humanitarian: Kenya’s security paradox: Police sent to Haiti as banditry plagues North Rift

- Elisabeth Witchel, Committee to Protect Journalists: At-risk journalists who must flee home countries often find few quick and safe options (June 17, 2021)

[btnsx id=”5768″]

To subscribe at no cost, please send an email to journal-isms+subscribe@groups.io and say who you are.

Facebook users: “Like” “Richard Prince’s Journal-isms” on Facebook.

Follow Richard Prince on Twitter @princeeditor

Richard Prince’s Journal-isms originates from Washington. It began in print before most of us knew what the internet was, and it would like to be referred to as a “column.” Any views expressed in the column are those of the person or organization quoted and not those of any other entity. Send tips, comments and concerns to Richard Prince at journal-isms+owner@

View previous columns (after Feb. 13, 2016).

View previous columns (before Feb. 13, 2016)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2018 (Jan. 4, 2019)

- Book Notes: Is Taking a Knee Really All That? (Dec. 20, 2018)

- Book Notes: Challenging ’45’ and Proudly Telling the Story (Dec. 18, 2018)

- Book Notes: Get Down With the Legends! (Dec. 11, 2018)

- Journalist Richard Prince w/Joe Madison (Sirius XM, April 18, 2018) (podcast)

- Richard Prince (journalist) (Wikipedia entry)

- February 2018 Podcast: Richard “Dick” Prince on the need for newsroom diversity (Gabriel Greschler, Student Press Law Center, Feb. 26, 2018)

- An advocate for diversity in the media is still pressing for representation, (Courtland Milloy, Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2017)

- Morgan Global Journalism Review: Journal-isms Journeys On (Aug. 31, 2017)

- Journal-isms’ Richard Prince Wants Your Ideas (FishbowlDC, Feb. 26, 2016)

- Richard Prince with Charlayne Hunter-Gault, “PBS NewsHour,” “What stagnant diversity means for America’s newsrooms” (Dec. 15, 2015)

- Book Notes: Journalists Follow Their Passions

- Book Notes: Journalists Who Rocked Their World

- Book Notes: Hands Up! Read This!

- Book Notes: New Cosby Bio Looks Like a Best-Seller

- Journo-diversity advocate turns attention to Ezra Klein project (Erik Wemple, Washington Post, March 5, 2014)

6 comments