Originally published May 29, 2022; updated May 29, 2023, and May 26, 2024

One Exposed U.S. Cover-Up About Atomic Bomb

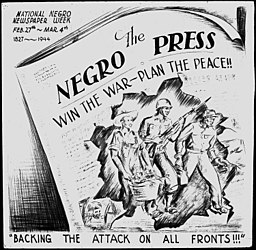

Homepage photo: The Double-V Campaign, cartoon by Charles Alston (Credit: Smithsonian)

Support Journal-ismsDonations are tax-deductible.

A 2024 contrast with these reports from World War II: In 2024, both the secretary of defense, Lloyd Austin, and the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr., are African American.

In addition, on Feb. 1, the Supreme Court declined to temporarily block race-conscious admissions at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, as it had done in June 2023 in ruling as unlawful the race-conscious admissions programs at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina.

The court’s decision did not extend to those military institutions, which include West Point, the Naval Academy and the Air Force Academy, because they have “potentially distinct interests,” Chief Justice John G .Roberts Jr. wrote in the majority opinion.

Black press war correspondent Charles H. Loeb gazes on the ruins of the Manila Hotel, a deluxe lodging set aflame by the Japanese during the battle for the liberation of Manila in the Philippines. “While hailed as a civic leader in Cleveland, his hometown, and more widely as a pioneering Black journalist, he was unappreciated for having exposed the bomb’s stealthy dangers at the dawn of the atomic age,” The New York Times said. (Credit: Loeb family photo)

One Exposed U.S. Cover-Up About Atomic Bomb

“In August 1944, an American soldier finishing up an Army survey was asked whether he had any further remarks. He did,” Michael E. Ruane wrote Dec. 20 in The Washington Post.

“ ‘White supremacy must be maintained,’ he wrote.

“ ‘I’ll fight if necessary to prevent racial equality. I’ll never salute a negro officer and I’ll not take orders from a negroe. I’m sick of the army’s method of treating … [Black soldiers] as if they were human. Segregation of the races must continue.’

“Another soldier wrote: ‘God has placed between us a barrier of color … We must accept this barrier and live, fight, and play separately.’

“These harsh views, and others, from the segregated Army of World War II, emerge in a new project at Virginia Tech that presents the uncensored results of dozens of surveys the service administered to soldiers during the war.

”Much of the material is being placed on the Internet for the first time, and a lot of it runs counter to the wholesome image of the war’s ‘greatest generation. . . .”

Roi Ottley, one of the few Black journalists to cover World War II for a mainstream newspaper, was writing about such racism at the time.

As this column noted in 2013, reporting on Mark A. Huddle’s “Roi Ottley’s World War II: The Lost Diary of an African American Journalist” (pictured):

As this column noted in 2013, reporting on Mark A. Huddle’s “Roi Ottley’s World War II: The Lost Diary of an African American Journalist” (pictured):

“Ottley’s story for PM, a New York newspaper, on relations between African American and white U.S. troops in Europe and both groups’ relations with their host countries is worth the price of this book.

“The noose of prejudice is slowly tightening around the necks of American Negro soldiers, and tending to cut off their recreation and associations with the British people,” the 1944 story begins. “For — to be frank — relations between Negro and white troops have reached the proportions of grave concern . . . in essence, there are those here who are still fighting the Civil War — this time on British soil.”

The above paragraphs were written last December. But as Americans celebrate Memorial Day 2022, they only hint at the bigger picture.

For one thing, while Ottley was reporting for the mainstream, many more Black journalists were telling the story of Black soldiers in the Black press.

Others of color had their own stories. There were the celebrated Navajo (Dine) “code talkers,” who were fluent in both their traditional tribal language and in English. They were used in the U.S. war effort to send secret messages in battle. But there were apparently no Native American war correspondents. After authoring “Pictures of Our Nobler Selves,” a history of Native journalists published in 1995, Mark Trahant messaged Journal-isms, “I didn’t find anyone.”

[James Giago Davies, editor of Native Sun Today in Rapid City, S.D., subsequently messaged, “There were very few educated or professional Natives eighty years ago. There is no way a local paper would have hired a Native for any writing position, and this held true well into the 1970’s. Even today, the last Native columnist the Rapid City Journal had, was white, despite the fact there were Native columnists they could have hired, columnists that beat out the man they did hire for Best Column on a routine basis.”]

In 2015, Linda Hervieux, a former editor at the Daily News in New York, wrote “Forgotten: The Untold Story of D-Day’s Black Heroes, At Home and At War.” It tells the story of the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion, the only unit of African American combat soldiers in the segregated U.S. Army to land on D-Day. “They stormed Omaha and Utah Beaches early on June 6, 1944. They’ve been written out of history. Movies don’t show them. Most books don’t mention them. But they were there.” (Credit: YouTube)

Same with Hispanic correspondents. None could be identified. Their absence might be explained by the climate of the times.

Writing in The Washington Post, journalist and author Marie Arana explained in 2019:

“Resentment against a growing Hispanic presence in cities and schools found voice in English-only edicts, emboldening white Americans to treat Latinos as an unwelcome foreign underclass. In the small Texas town of Three Rivers, a Hispanic soldier returning from World War II in a coffin was denied a proper funeral. Farther west, in California, political cartoonists and crime novelists were characterizing a rising tide of young Mexican American males as a menace.

“In Los Angeles, thousands of soldiers and civilians descended on Hispanic youths in 1943 in a virulent attack known as the Zoot Suit Riots. Brown Americans were pushed into segregated communities, forbidden from serving on juries, their children made to attend ‘Mexican’ schools. In southern Arizona, migrant farmworkers were kidnapped, robbed, tortured — their feet seared over fire — and told to go home.”

Meanwhile, Japanese Americans were herded into internment camps. Still, in 2010, the Los Angeles chapter of the Asian American Journalists Association located two correspondents who reported on World War II and honored them as pioneers: Larry Nakatsuka of the Honolulu Star-Bulletin, who covered the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, and Jen-Chung Chang, who was also president of Foreign Press Club in Tokyo. More on them later.

Representing the most numerous of the groups of color, the Black press had the numbers to more effectively call out racial inequality in the military and in the nation.

Sadly, one of their number died in the Korean conflict, becoming the first Black journalist to die in a 20th-century war.

“Soon after the fighting started in Korea in June 1950, the Negro press had its war correspondents on the way to cover the conflict,” according to the Negro Yearbook.

“Soon after the fighting started in Korea in June 1950, the Negro press had its war correspondents on the way to cover the conflict,” according to the Negro Yearbook.

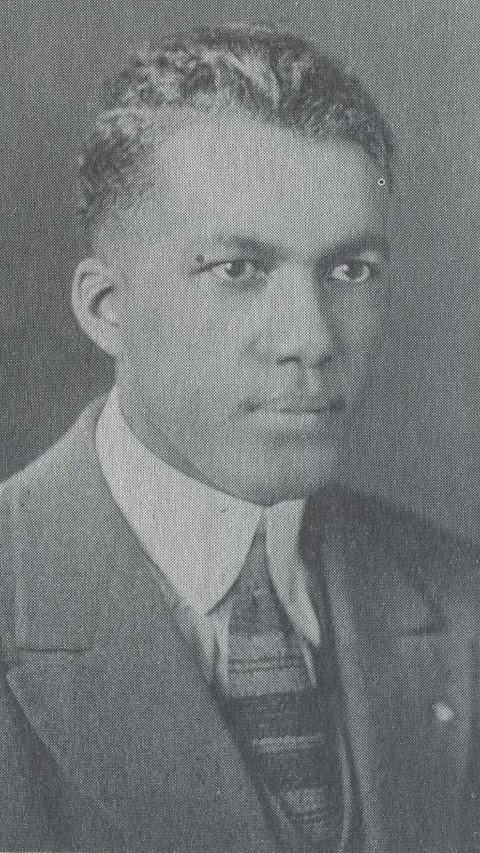

“Two men were assigned this task, Albert L. Hinton (pictured), managing editor, Journal and Guide, Norfolk, Va., who represented the NNPA group of papers,” a reference to the National Negro Publishers Association, known today as the National Newspaper Publishers Association, “and James L. Hicks, Afro-American staff member, who represented the Afro-American chain.

“Hinton and Hicks traveled 6,000 miles together as far as Tokyo, where they took separate planes to the

Korean front. However, Hinton never reached his destination, for his plane, a C-47 transport, plunged into the sea on the 110-mile jaunt from Tokyo to southern Korea.”

Hinton died with 25 others.

Before Korea, there was World War II. Gerald Horne wrote about the role of the Black press then in his 2017 book, “The Rise & Fall of the Associated Negro Press: Claude Barnett’s Pan-African News and the Jim Crow Paradox.”

Ted Stanford, left, of The Pittsburgh Courier interviews U.S. Army Sgt. Morris O. Harris of the 784th Tank Battalion of the 9th Army, March 28, 1945. (Credit: National Archives)

“By 1944, the ANP had upped the number of foreign correspondents on its roster . . . As of 1943 Barnett ascertained that there were ‘over 100,000 Negro troops overseas’ and by 1944 the ANP listed in London, Lagos, the Panama Canal Zone, the Southwest Pacific, Johannesburg, Honolulu, Moscow and Teheran.”

Horne continued, “By 1944, the ANP also had added correspondents in India and three others listed ‘somewhere in [the] South Pacific,’ another listed as ‘somewhere in Africa,’ and yet another listed simply as embedded with the U.S. Navy. They faced stiff competition from the [Chicago] Defender, the [Pittsburgh] Courier, the Journal and Guide, and other Negro press organs that had managed to employ foreign correspondents.

“There was official resistance to providing credentials to ANP and these other correspondents because of the perception of the Negro press as potentially seditious; thus, when Barnett reported these additional correspondents, he mentioned that ‘the army is capitulating’ and granting them credentials after pressure was placed upon them.”

Prominent among Black correspondents was Charles H. Loeb, whose articles were distributed by the competing National Negro Publishers Association, The New York Times reported last year. Loeb advanced with U.S. troops into the Philippines, survived a kamikaze attack and filed a number of detailed reports from Japan, including ones on Hiroshima’s bombing and the nation’s formal surrender.

In “Loeb Reflects on Atomic Bombed Area,” as the headline read in The Atlanta Daily World of Oct. 5, 1945, two months after Hiroshima’s ruin, Loeb “told how bursts of deadly radiation had sickened and killed the city’s residents. His perspective, while coolly analytic, cast light on a major wartime cover up,” William J. Broad wrote for the Times.

Among the most prominent Black correspondents were the Pittsburgh Courier’s Edgar Rouzeau, the first Black reporter to receive war correspondent accreditation, Mark Whitaker writes in his 2018 book about Black Pittsburgh, “The Untold Story of Smoketown: The Other Great Black Renaissance,” and the legendary Frank Bolden Jr.

“The sweltering, vermin-infested jungles of [Burma] were a long way from Wylie Avenue, but Bolden brought the same intrepid dedication in his coverage of the troops there, particularly those deployed to build the famous Burma Road,“ Herb Boyd would write for the New York Amsterdam News. “His stories captured the challenge the Black soldiers faced on the job and on racial hostility. There was a continuing series of stories combating the negative reports on African-American soldiers and their alleged cowardice.

“Bolden seemed to be everywhere in the military, and at one time was even the house guest of the Indian leaders Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, both of whom enthusiastically assured the reporter of their support for the Black civil rights struggle. Other notables who agreed to answer Bolden’s questions were President Roosevelt, Winston Churchill and Josef Stalin.”

Other prominent members of the Black press included Enoch Waters of the Chicago Tribune, Ollie Stewart of the Afro-American and cartoonist Ollie Harrington. They linked Jim Crow at home with segregation in the military. They called attention to discrimination against Black soldiers as they celebrated their triumphs.

When, in 2012, the legendary Tuskegee Airmen were the subject of “Red Tails,” a George Lucas movie about their exploits, Dr. Roscoe Brown, one of the Airmen, told the National Association of Black Journalists, ‘It was Black journalists that brought us to the attention of the Black community throughout the country during the time we were flying and fighting.”

During the war, some in the Black press reported favorably about the Soviet Union, a U.S. ally for wartime purposes, for its supposed lack of racism, or about nonwhite Japan. Others raised the issue of European colonialism. When in 1943, the president-elect of Liberia visited the United States, New York correspondent Ernest Johnson reported that the west African was “very much interested in ‘selling’ Liberia to American Negroes as an ‘asylum.’ When that leader visited the White House, Johnson instructed the ANP to request that five Negro correspondents be given temporary credentials.”

Also covering the war from a Black perspective, correspondent Chatwood Hall noted that it was the African Abram Hannibal who centuries earlier, “helped build and arm the great Kronstadt fortress at the head of the Gulf of Finland, which served to prevent the Germans from reaching Leningrad by sea in this war.” It was a battle that rivaled Stalingrad in its ferocity and intensity, Horne wrote.

And in a reference to a city very much in today’s news, Horne noted that when Kyiv, Ukraine, “was pummeled during the war,” Hall illuminated his story by discussing the Hotel Continental, “which housed many Negro tourists in the past,” but was now “a pile of brick, stone and steel.”

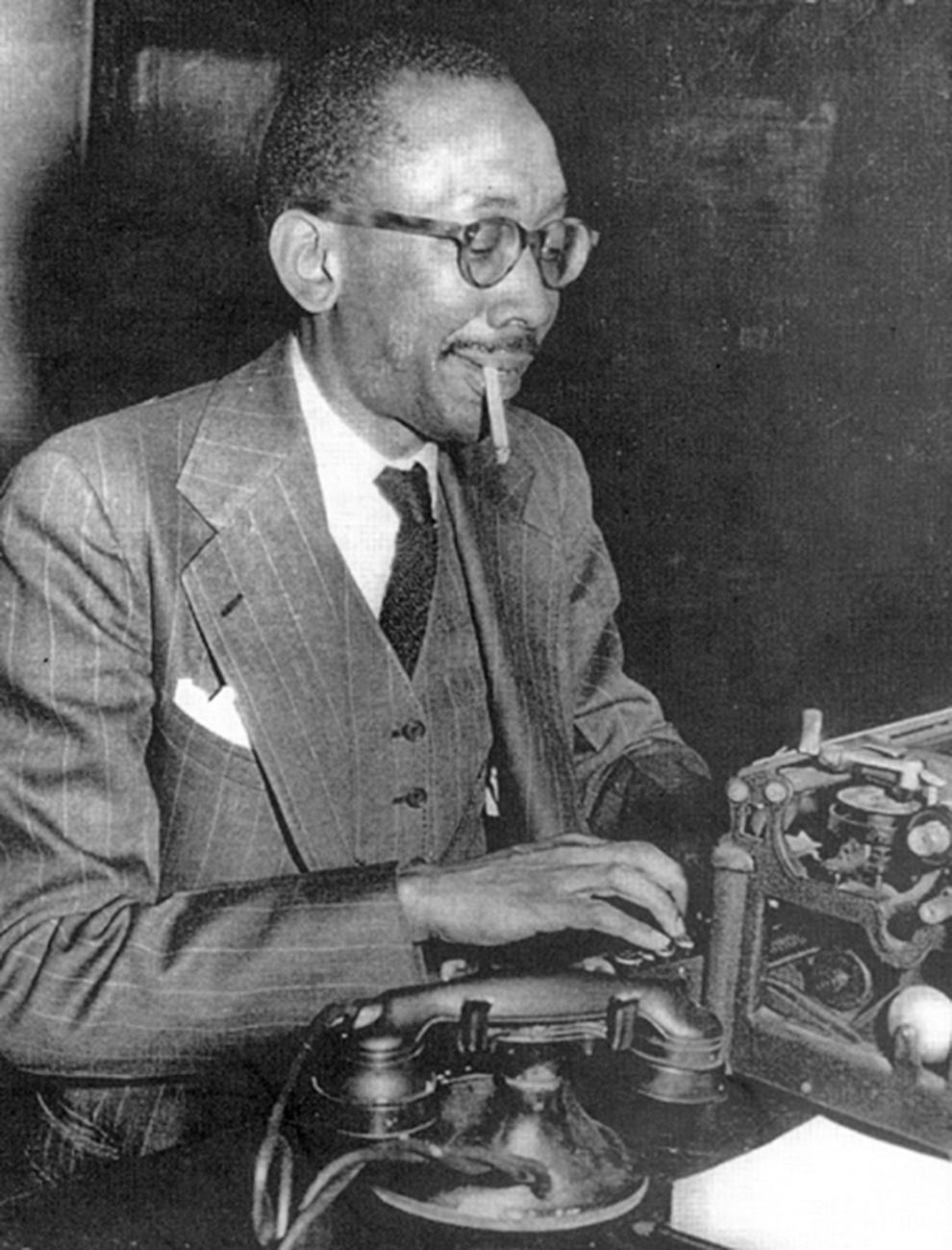

Hall was otherwise known as Homer Smith Jr. (pictured), who in 2002 received the first Legacy Award from the National Association of Black Journalists. [“From the President” column, PDF]

Hall was otherwise known as Homer Smith Jr. (pictured), who in 2002 received the first Legacy Award from the National Association of Black Journalists. [“From the President” column, PDF]

Smith wrote an autobiography “Black Man in Red Russia,” in 1964.

As recounted by BlackPast.org, “Smith had been sending articles to black American newspapers since 1932 while he worked at the Moscow Post Office.

“When Germany invaded Russia in the summer of 1941, he was now a full-time war correspondent for the Associated Negro Press and in 1944 he became half of the two-person Associated Press team in Moscow. As a correspondent Smith covered the initial German invasion of the Soviet Union, the siege of Moscow, the devastation of Sevastopol in the Crimea, and the excavation of deceased Polish Army officers in the Katyn Forest in Poland. Smith also reported on his 1945 visit to the Nazi extermination camp in Majdanek, Poland.

“While most attention was focused on the Jewish concentration camp victims and survivors, Smith saw the postmortem photographs of Senegalese troops who were captured by the Germans in 1940 as they defended the Maginot Line in Northeastern France. Many of them were transferred to Majdanek where they died.”

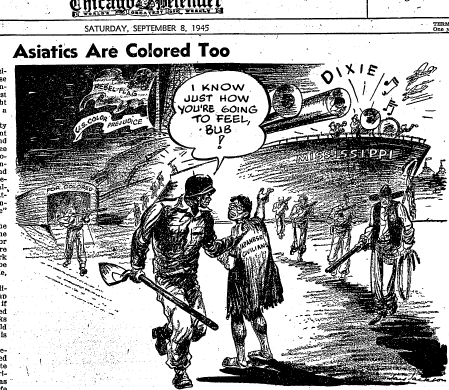

A wartime cartoon in the Atlanta Daily World showed Hitler being embraced by Dixiecrats. Another, in the Chicago Defender, showed a Black soldier saying to a Japanese civilian, “I know just how you’re going to feel, bub.” But most in the Black press supported the war effort.

Still, as Patrick S. Washburn wrote in 1986 in “A Question of Sedition: The Federal Government’s Investigation of the Black Press During World War II,” “an intense battle raged within the highest levels of [Franklin D.] Roosevelt’s government” over censoring the Black press.

“On the side of suppressing, or at least silencing, the black press was the powerful team of FDR and [FBI Director] J. Edgar Hoover, working virtually alone; on the other side was Attorney General Francis Biddle, whose earlier association with Oliver Wendell Holmes had made him an ardent defender of civil liberties.”

Referring to John Sengstacke, publisher of The Chicago Defender, The New York Times summarized the outcome. “Biddle promised Sengstacke that the Justice Department would not indict any of the black publishers for sedition. Sengstacke, in turn, said that he could not promise that the black press would tone down its criticism in the future because he could not speak for the other publishers [but that] if the black papers were granted interviews with top government officials, they would be ‘glad’ to cooperate with the war effort. . . .”

Aside from the war correspondents, other Black journalists played roles.

Ted Poston (pictured), an early Black pioneer in the white press, most notably at the New York Post, worked as head of the Negro News Desk in the U.S. Office of War Information. “Poston and his fellow Black Cabinet members were treading a thin line as they advocated for blacks within the government yet also for the government among blacks,” Kathleen A. Hauke wrote in her 1998 biography, “Ted Poston: Pioneer American Journalist.”

Ted Poston (pictured), an early Black pioneer in the white press, most notably at the New York Post, worked as head of the Negro News Desk in the U.S. Office of War Information. “Poston and his fellow Black Cabinet members were treading a thin line as they advocated for blacks within the government yet also for the government among blacks,” Kathleen A. Hauke wrote in her 1998 biography, “Ted Poston: Pioneer American Journalist.”

Ethel Payne (pictured), honored last month with a Lifetime Achievement Award from the White House Correspondents’ Association, was working as a librarian in Chicago, 29 years old, writing letters to the editor of the Chicago Tribune and Chicago Defender, while an activist for the NAACP. Payne helped organize a five-day “We Are Americans, too” conference in Chicago. Bloody riots took place in Detroit in 1943 as it was being planned.

Ethel Payne (pictured), honored last month with a Lifetime Achievement Award from the White House Correspondents’ Association, was working as a librarian in Chicago, 29 years old, writing letters to the editor of the Chicago Tribune and Chicago Defender, while an activist for the NAACP. Payne helped organize a five-day “We Are Americans, too” conference in Chicago. Bloody riots took place in Detroit in 1943 as it was being planned.

“The focus would be on ending ‘Jim Crow in uniform’ and the conference would include strategy sessions on eliminating military segregation and creating a program to do the same with American civilian life,” James McGrath Morris wrote in his 2015 biography, “Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne, the First Lady of the Black Press.“

Carl Rowan (pictured), who would become the mainstream press’ most widely circulated Black columnist, became a naval officer at age 19, serving as a communications officer on several ships until he was discharged in 1946.

Carl Rowan (pictured), who would become the mainstream press’ most widely circulated Black columnist, became a naval officer at age 19, serving as a communications officer on several ships until he was discharged in 1946.

“After the war, Rowan was dismayed by the lack of respect for Black GIs, even though his father had told him that when he and other Black soldiers returned home after WWI, ‘White folks got real mean,‘ ” Dorothy Butler Gilliam wrote for PBS’ “American Experience.” “In one particularly egregious case at the close of WWII, Isaac Woodward, a Black Army sergeant, was taken off a bus in South Carolina while traveling home to North Carolina. He was brutally beaten by the local sheriff to the point that both of his retinas were damaged, and he was blinded. The sheriff was later tried but found not guilty. The verdict strengthened Rowan’s resolve to become a journalist. ‘I believed that I could change things,’ he recalled” in his memoir.

In March, the Seattle Times marked the 80th anniversary of the first removals of Japanese Americans from their homes on the West Coast. The newspaper apologized for its coverage.

“A rare number of media outlets — most notably the Bainbridge Island Review — took a principled stand against incarceration. Others, including The Seattle Times, did not. Eight decades later, Seattle Times Publisher Frank Blethen called that decision a ‘low point’ in the paper’s history,” wrote Times columnist Naomi Ishisaka.

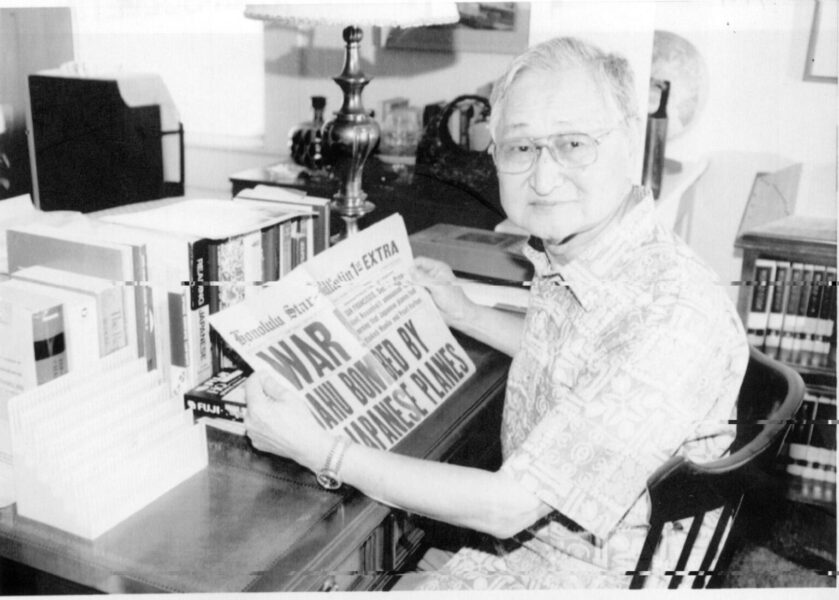

Larry Nakatsuka, the first Japanese American reporter in Hawaii, holds a Honolulu Star newspaper from Dec. 7, 1941. The front page reads “Oahu Burned by Japanese Planes.” (Credit: Asian American Journalists Association).

In 2000, the Asian American Journalists Association awarded Nakatsuka its Lifetime Achievement Award.

“The first Japanese American to report for the Star-Bulletin, Larry Nakatsuka was assigned in 1939 to cover Japanese news,” the newspaper reported in his 2006 obituary. “Two years later, that included confronting the Japanese consul general: ‘Do you know that Japanese planes are bombing Pearl Harbor?’

“At the Japanese consulate on Dec. 7, 1941, Nakatsuka would recall that the consul general, Nagao Kita, appeared surprised at his question, and said he thought the gunfire he heard came from American ships and planes on maneuver.

“The reporter sped back to the Star-Bulletin’s Merchant Street office to write his story and returned to the Japanese consulate in time to see police dousing flames from papers being burned. His article appeared in the second and third extra editions that afternoon.”

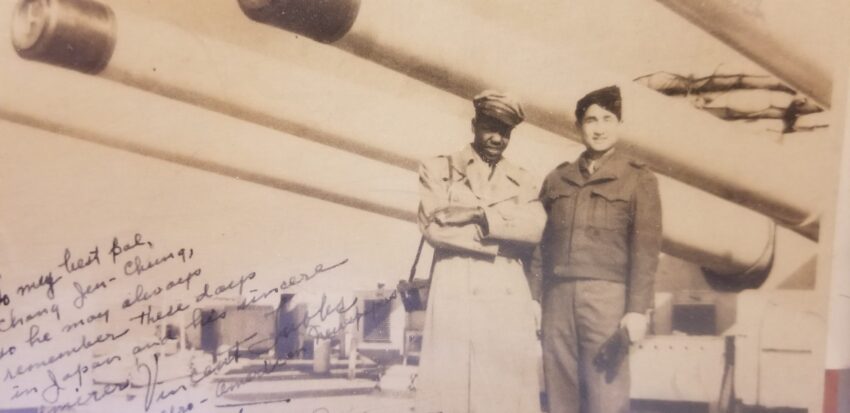

Allied correspondents Jen-Chung Chang of the Central Daily News, right, and Vincent Tubbs of the Baltimore Afro-American. (Courtesy Ti-Hua Chang)

Also honored at AAJA’s 2010 ceremony was Chang, represented by his son, longtime New York television reporter Ti-Hua Chang.

“My Dad worked for the Central Daily News” in Chongqing, China, Chang messaged. “He covered the Burma campaign as an Allied correspondent with General Joe Stillwell aka Vinegar Joe. Also the retaking of Korea. The Japanese surrender on the USS Missouri, was the first Allied correspondent to go to Hiroshima just one month after the dropping of the Atomic Bomb and had the last interview with the war criminal Tojo. My Dad became an Asian American but while reporting was a Chinese citizen.”

Isaac Cubillos, a former vice president of Military Reporters and Editors Association and author of the “Military Reporters Stylebook and Reference Guide,” messaged Journal-isms last week about his organization, including what he thinks the holiday might mean for some of his fellow members.

“From what I gather from my members’ feed, some are working covering Memorial Day events. Many others are spending time with family, but all are mindful of what the day means to them professionally and personally. Some, like Kelly Kennedy, former soldier and now managing editor of The War Horse News, covered Iraq, and saw many die while there.

“Greg Mathieson, a combat cameraman, also recorded death on the front lines in Iraq and Afghanistan. So many of our members personally know somebody who died overseas, including fellow journalists who died covering the frontlines. For us, it truly is a time of reflection on the sacrifices made, and the human cost of war.”

- Matthew Delmont, The Conversation: From WWII to Charlottesville: A Brief History of African-Americans fighting Fascism and Racism (May 25, 2020)

- Alissa Falcone, Drexel University: Communications Professor Analyzes Local Media Coverage of Japanese-American Incarceration Camps (July 6, 2015)

- Journal-isms: “A Multicultural World War II” (June 2, 2004)

- Journal-isms: World War I’s Black Journalists Had to Fight Their Own Government (Nov. 26, 2018)

- John Smelcer, NPR: The Other WWII American-Internment Atrocity (Feb. 21, 2017)

- Randall Yip, AsAmNews: Remembering my dad on Memorial Day (May 27, 2019)

To subscribe at no cost, please send an email to journal-isms+subscribe@groups.io and say who you are.

Facebook users: “Like” “Richard Prince’s Journal-isms” on Facebook.

Follow Richard Prince on Twitter @princeeditor

Richard Prince’s Journal-isms originates from Washington. It began in print before most of us knew what the internet was, and it would like to be referred to as a “column.” Any views expressed in the column are those of the person or organization quoted and not those of any other entity. Send tips, comments and concerns to Richard Prince at journal-isms+owner@

View previous columns (after Feb. 13, 2016).

View previous columns (before Feb. 13, 2016)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2018 (Jan. 4, 2019)

- Book Notes: Is Taking a Knee Really All That? (Dec. 20, 2018)

- Book Notes: Challenging ’45’ and Proudly Telling the Story (Dec. 18, 2018)

- Book Notes: Get Down With the Legends! (Dec. 11, 2018)

- Journalist Richard Prince w/Joe Madison (Sirius XM, April 18, 2018) (podcast)

- Richard Prince (journalist) (Wikipedia entry)

- February 2018 Podcast: Richard “Dick” Prince on the need for newsroom diversity (Gabriel Greschler, Student Press Law Center, Feb. 26, 2018)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2017 — Where Will They Take Us in the Year Ahead?

- Book Notes: Best Sellers, Uncovered Treasures, Overlooked History (Dec. 19, 2017)

- An advocate for diversity in the media is still pressing for representation, (Courtland Milloy, Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2017)

- Morgan Global Journalism Review: Journal-isms Journeys On (Aug. 31, 2017)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2016

- Book Notes: 16 Writers Dish About ‘Chelle,’ the First Lady

- Book Notes: From Coretta to Barack, and in Search of the Godfather

- Journal-isms’ Richard Prince Wants Your Ideas (FishbowlDC, Feb. 26, 2016)

- “JOURNAL-ISMS” IS LATEST TO BEAR BRUNT OF INDUSTRY’S ECONOMIC WOES (Feb. 19, 2016)

- Richard Prince with Charlayne Hunter-Gault, “PBS NewsHour,” “What stagnant diversity means for America’s newsrooms” (Dec. 15, 2015)

- Book Notes: Journalists Follow Their Passions

- Book Notes: Journalists Who Rocked Their World

- Book Notes: Hands Up! Read This!

- Book Notes: New Cosby Bio Looks Like a Best-Seller

- Journo-diversity advocate turns attention to Ezra Klein project (Erik Wemple, Washington Post, March 5, 2014)

When you shop @AmazonSmile, Amazon will make a donation to Journal-Isms Inc. https://t.co/OFkE3Gu0eK

— Richard Prince (@princeeditor) March 16, 2018

Reposted, Nov. 11, 2022; updated May 30, 2024