Irish, African Diaspora Have Complicated History

Nominate a J-Educator Who Promotes Diversity

Homepage photo: Credit African American Irish Diaspora Network

Support Journal-ismsDonations are tax-deductible.

Irish, African Diaspora Have Complicated History

By Isaiah J. Poole

This St. Patrick’s Day is taking on special significance at Howard University as a contingent of 19 students from University College Dublin in Ireland arrive for a weeklong visit.

Their stay is the latest example of the work of an organization launched by a Black media executive and consultant to heal the breaches in a long and complicated relationship between Black and Irish Americans.

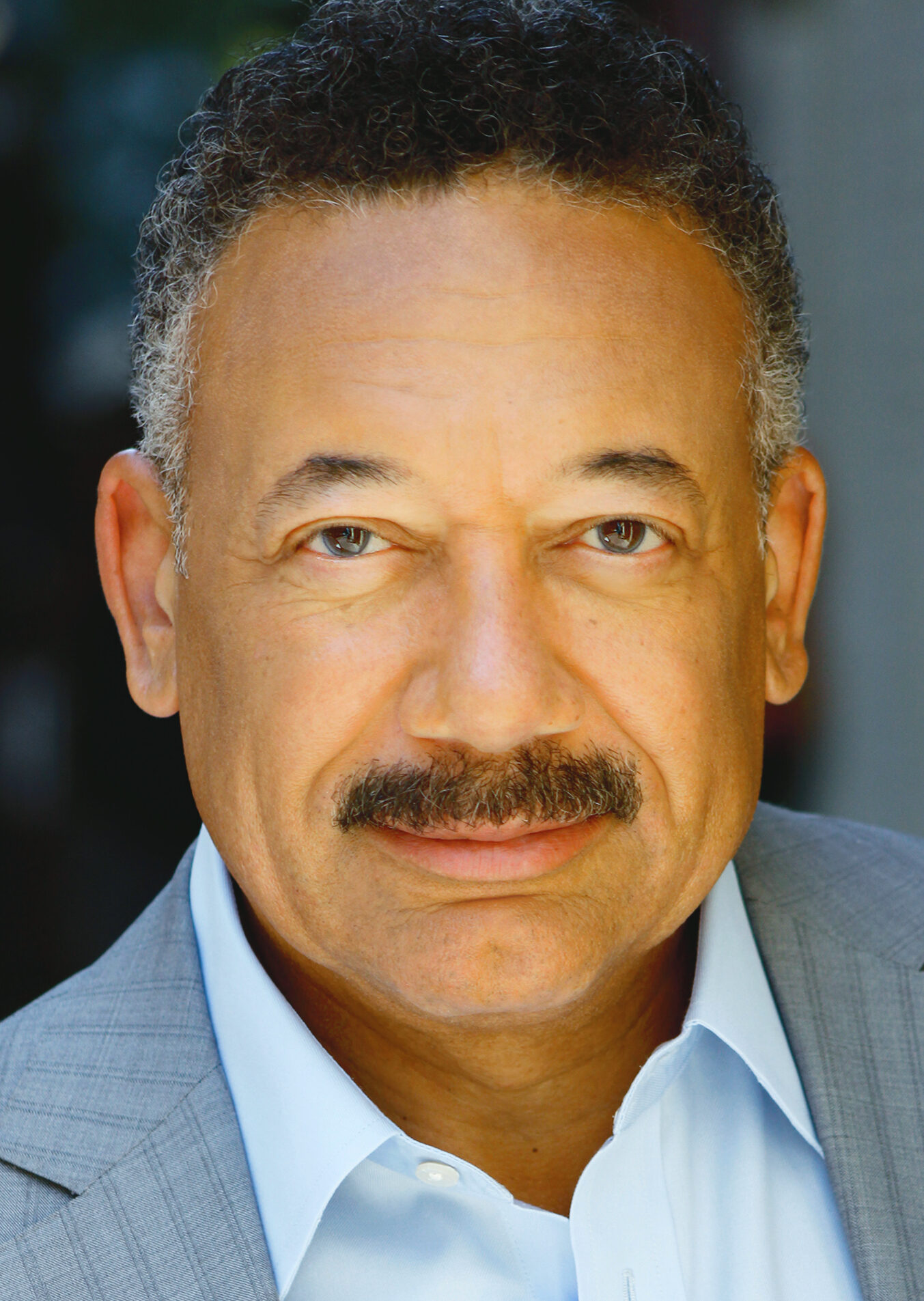

The exchange between the Howard University School of Business and the Michael Smurfit Graduate Business School at University College of Dublin was organized with the help of the African American Irish Diaspora Network, founded by Dennis Brownlee (pictured), whose work in media included the launch in 2000 of the short-lived New Urban Entertainment cable network. Brownlee spoke about the organization and the history of Black-Irish relations at the Journal-isms Roundtable on Feb. 19, as Black History Month was well underway.

The exchange between the Howard University School of Business and the Michael Smurfit Graduate Business School at University College of Dublin was organized with the help of the African American Irish Diaspora Network, founded by Dennis Brownlee (pictured), whose work in media included the launch in 2000 of the short-lived New Urban Entertainment cable network. Brownlee spoke about the organization and the history of Black-Irish relations at the Journal-isms Roundtable on Feb. 19, as Black History Month was well underway.

The diaspora network says it sponsors educational exchanges and other activities designed to understand and build upon “the deep connections and parallels in the social justice and civil rights movement in Ireland and the United States.”

Forty-two people were on the Feb. 19 Zoom call with Rep. James Clyburn, D-S.C., and Dennis Brownlee, founder of the African American Irish Diaspora Network; 106 others had watched on Facebook by March 16 and 105 more on YouTube. (Credit: YouTube)

The St. Patrick’s Day arrival of the Dublin students follows a weeklong visit in February of 14 Howard University School of Business students and faculty to the Dublin university’s Michael Smurfit Graduate Business School. That university is also providing two scholarships a year to Howard students to earn a graduate business degree there.

“We are looking to expand that program to other historically Black colleges and universities,” Brownlee said.

Nearly 40 percent of Black Americans have some Irish ancestry, said Brownlee, the husband of the late Washington Post reporter and editor Vivian Aplin-Brownlee. He is one of them.

“As I was growing up in the ‘60s and ‘70s in Cleveland, Ohio, my mother would tell me that we had some Irish ancestry in our family background, and specifically Scots-Irish from the North, and she was very proud of that ancestry,” Brownlee said.

But Brownlee did not delve into that aspect of his heritage until about 12 years ago, when having moved to Washington, he began talking to his next-door neighbor, who was Irish, and disclosed that he, too, had Irish ancestry. “She took it very seriously, started introducing me into the Irish community, and the reception that I got was so warm and welcoming it drove me to explore more about the whole history between the Irish and African Americans.”

That exploration culminated in launching the African American Irish Diaspora Network in February 2020 to forge relationships between Black and Irish people through their shared heritage and culture.

“When the Irish government heard that we were planning to do that, they got behind the launch vigorously, and actually staged our launch event at the residence of the consul general in New York, which brought together a really nice, diverse crowd,” Brownlee said. “There was a great spirit of coming together at that launch event, and we’ve received a lot of support from the Irish Government since then.”

Jude Hughes, a longtime Irish activist and advocate with the Association of Mixed Race Irish, described his life as the son of a Black father and white Irish mother in a Feb. 1 talk sponsored by New York University’s John Brademas Center, the African American Irish Diaspora Network and the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Hughes said that while Ireland was a country of emigration, now it is one of immigration. Dublin is now a multicultural city. (Credit: YouTube)

Ties between Black and Irish people in America, both good and bad, extend at least as far back as the 1830s and the potato famine in Ireland that began in 1845, leading to the deaths of more than one million people and prompting hundreds of thousands to seek refuge on the other side of the Atlantic.

Many settled in New York, most notably in what was known in the mid-1800s as the Five Points neighborhood in lower Manhattan. Built on top of what had been a freshwater pond before it was badly polluted by businesses that surrounded it, the neighborhood of poorly constructed housing and disease-breeding conditions became the home of last resort for both poor Irish immigrants and freed Black people.

At first, according to Brownlee, recently emancipated Black people and the new Irish immigrants found camaraderie in their shared outsider status. One outgrowth was “the merger of Irish dance and African dance at the dance halls and saloons in Five Points, and the dance competitions that were almost like sporting events,” out of which emerged the art form of American tap dance.

A similar cultural melding was taking place in Appalachia, where the intermingling of traditional African and traditional Irish melodies and instruments produced what became known as bluegrass.

But at the outset of the Civil War, an inequitable Union Army draft system stoked tensions between Irish people, disproportionately drawn into conscription because they did not have the resources to buy their way out, as had descendants of other European immigrant groups, and Black people, who were excluded from the draft.

Adding to the tensions was the fear that if Southern slaves were freed, they would flood the North and displace the Irish in the job market. In New York, the tensions exploded in July 1863 in one of several “draft riots.” On that day, Irish rioters burned down a draft office, hunted down nearly a dozen Black men who were lynched after being brutally beaten, and killed some whites as well. The riots sparked a mass movement of Black residents out of Five Points to what became Harlem. Deep tensions have marked Irish-Black relations ever since, surfacing in places such as Chicago, where in 1966 Martin Luther King Jr. said he had never “seen, even in Mississippi and Alabama, mobs as hateful as I’ve seen here,” and in Boston, where Irish Catholic neighborhoods engaged in forceful resistance to school integration during the 1970s.

“You have that part of the history,” Brownlee said, “and that is acknowledged on the part of the Irish today, who want to change the image and relationship, and any preconceived notions about the Irish that African Americans might have, as well as to reverse any or as much . . . negativity on the part of the Irish toward African Americans that exist even still today in the United States.”

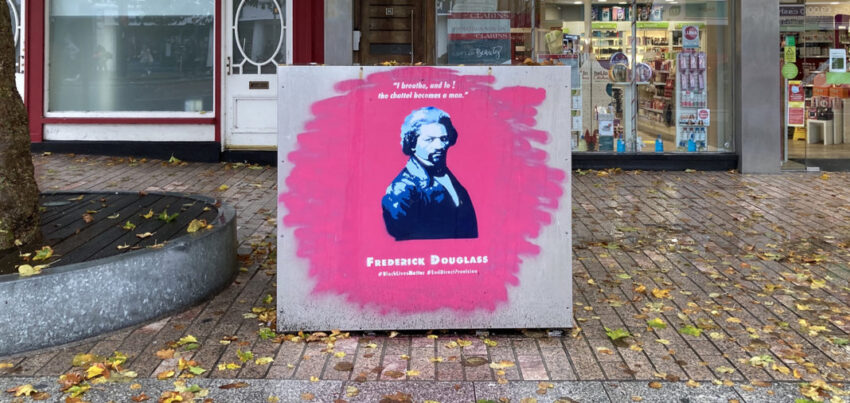

Also part of Irish-Black history is the experience of Black leaders such as Frederick Douglass, who went to Ireland in 1845. “That visit was very transformative for him in his life and in his career,” Brownlee said — so much so that Douglass wrote in a 1846 letter to white abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, “I can truly say, I have spent some of the happiest moments of my life since landing in this country … the entire absence of every thing that looked like prejudice against me, on account of the color of my skin — contrasted so strongly with my long and bitter experience in the United States, that I look with wonder and amazement on the transition.”

Brownlee said as many as 20 or more other Black abolitionists traveled to Ireland in the 1800s. They “also had an impact in Ireland and got much support from the Irish for the abolitionist movement.”

The actor Ira Aldridge, namesake of a prominent theater at Howard University, toured Ireland in the 1830s. In Killarney, Aldridge was described as the “great magnet of popular attraction” in the town and the only person “upon whose merits there is no disagreement,” the Irish Times reported last year.

During a question-and-answer session at the Roundtable, Barbara Reynolds, author and former syndicated columnist, recounted her experience working in a newsroom dominated by white Irish American men who made her feel disrespected.

But then she had a chance to go to Ireland herself. “I had never seen so many friendly people who just embraced me. You know, just these lovely, wonderful people,” Reynolds said.

On the other hand, journalist Roger Witherspoon said that up until the 1980s, “80 percent of the violent crime in Boston was white on Black, and it was Irish attacking us … Where does this antipathy come from?”

It is true, Brownlee replied, that as Irish people assimilated into America, as a group they took on the attitudes and behaviors of white supremacy. “They came to a country that accepted them. This country was founded on slavery. They adopted the system that was here, and they adopted the racism that was underpinning that whole system and structure,” he said.

That continues today, reflected in neo-Nazi groups that are appropriating elements of Irish culture, iconography and language to promote White supremacy, Brownlee said.

Nonetheless, “I think the bottom line at this point is that you have the Irish government, the people of Ireland, and a large proportion of the Irish people here who want to build bridges to the African American community. And there are opportunities in that for us.

“There are opportunities in education, opportunities in business, and opportunities for cultural development… And I think that also in bringing African American kids together with Irish kids, they can build relationships that can grow over a lifetime, and inure to the benefit of all parties.”

- Belfast City Council: Statue of anti-slavery campaigner Frederick Douglass moves a step closer (Sept. 7, 2022)

- Ron Cassie, Baltimore magazine: On St. Patrick’s Day: Remembering Frederick Douglass’ Exile in Ireland (Feb. 14)

- EssentiallySports: “Holy Cow! Really?”: When a Beloved Comedian Was Dumbfounded After Learning He Was Related to MLB Great Derek Jeter

- Galway Advertiser, Ireland: Obama, O’Connell, and Douglass (May 19, 2011)

- Journal-isms: Obama Invokes Frederick Douglass on Irish Trip (scroll down) (May 26, 2011)

- Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art, New York: MoMA Presents St. Clair Bourne’s The Black and the Green, Mar 8–14, 2023

- Niall O’Dowd, Irish Central: New African American Irish network announced to build ties (Feb. 28, 2020)

Nominate a J-Educator Who Promotes Diversity

Beginning in 1990, the Association of Opinion Journalists, now part of the News Leaders Association, annually granted a Barry Bingham Sr. Fellowship — actually an award — “in recognition of an educator’s outstanding efforts to encourage minority students in the field of journalism.”

Since 2000, the recipient has been awarded an honorarium of $1,000 to be used to “further work in progress or begin a new project.”

Past winners include James Hawkins, Florida A&M University (1990); Larry Kaggwa, Howard University (1992); Ben Holman, University of Maryland (1996); Linda Jones, Roosevelt University, Chicago (1998); Ramon Chavez, University of Colorado, Boulder (1999); Erna Smith, San Francisco State (2000); Joseph Selden, Penn State University (2001); Cheryl Smith, Paul Quinn College (2002); Rose Richard, Marquette University (2003).

Also, Leara D. Rhodes, University of Georgia (2004); Denny McAuliffe, University of Montana (2005); Pearl Stewart, Black College Wire (2006); Valerie White, Florida A&M University (2007); Phillip Dixon, Howard University (2008); Bruce DePyssler, North Carolina Central University (2009); Sree Sreenivasan, Columbia University (2010); Yvonne Latty, New York University (2011); Michelle Johnson, Boston University (2012); Vanessa Shelton, University of Iowa (2013); William Drummond, University of California at Berkeley (2014); Julian Rodriguez of the University of Texas at Arlington (2015); David G. Armstrong, Georgia State University (2016); Gerald Jordan, University of Arkansas (2017), Bill Celis, University of Southern California (2018); Laura Castañeda, University of Southern California (2019); Mei-Ling Hopgood, Northwestern University (2020); Wayne Dawkins, Morgan State University (2021); and Marquita Smith of the University of Mississippi (2022).

Nominations may be emailed to Richard Prince, Opinion Journalism Committee, richardprince (at) hotmail.com. The deadline is April 7. Please use that address only for NLA matters.

To subscribe at no cost, please send an email to journal-isms+subscribe@groups.io and say who you are.

Facebook users: “Like” “Richard Prince’s Journal-isms” on Facebook.

Follow Richard Prince on Twitter @princeeditor

Richard Prince’s Journal-isms originates from Washington. It began in print before most of us knew what the internet was, and it would like to be referred to as a “column.” Any views expressed in the column are those of the person or organization quoted and not those of any other entity. Send tips, comments and concerns to Richard Prince at journal-isms+owner@

View previous columns (after Feb. 13, 2016).

View previous columns (before Feb. 13, 2016)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2018 (Jan. 4, 2019)

- Book Notes: Is Taking a Knee Really All That? (Dec. 20, 2018)

- Book Notes: Challenging ’45’ and Proudly Telling the Story (Dec. 18, 2018)

- Book Notes: Get Down With the Legends! (Dec. 11, 2018)

- Journalist Richard Prince w/Joe Madison (Sirius XM, April 18, 2018) (podcast)

- Richard Prince (journalist) (Wikipedia entry)

- February 2018 Podcast: Richard “Dick” Prince on the need for newsroom diversity (Gabriel Greschler, Student Press Law Center, Feb. 26, 2018)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2017 — Where Will They Take Us in the Year Ahead?

- Book Notes: Best Sellers, Uncovered Treasures, Overlooked History (Dec. 19, 2017)

- An advocate for diversity in the media is still pressing for representation, (Courtland Milloy, Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2017)

- Morgan Global Journalism Review: Journal-isms Journeys On (Aug. 31, 2017)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2016

- Book Notes: 16 Writers Dish About ‘Chelle,’ the First Lady

- Book Notes: From Coretta to Barack, and in Search of the Godfather

- Journal-isms’ Richard Prince Wants Your Ideas (FishbowlDC, Feb. 26, 2016)

- “JOURNAL-ISMS” IS LATEST TO BEAR BRUNT OF INDUSTRY’S ECONOMIC WOES (Feb. 19, 2016)

- Richard Prince with Charlayne Hunter-Gault, “PBS NewsHour,” “What stagnant diversity means for America’s newsrooms” (Dec. 15, 2015)

- Book Notes: Journalists Follow Their Passions

- Book Notes: Journalists Who Rocked Their World

- Book Notes: Hands Up! Read This!

- Book Notes: New Cosby Bio Looks Like a Best-Seller

- Journo-diversity advocate turns attention to Ezra Klein project (Erik Wemple, Washington Post, March 5, 2014)