Intended Lesson Made Some ‘Uncomfortable’

Blacks Expect Racism to Worsen in Their Lifetimes

COVID Relief Led to ‘Greatest Grift in U.S. History’

What a Story! Largest Known U.S. Slave Auction

Progress on Making Ebony, Jet Photo Archives Public

Stanley Terrell, Newark Journalist, Dies at 74

Short Takes: That ill-fated Black American journalists’ trip to Nigeria; Alfredo Corchado, Angela Kocherga, Lori Montenegro and Enrique Flor Zapler; Christopher Farley; John X. Miller; Michael Tyler; Black Public Media; Pat Robertson and Africa; Caitlin Dickerson; Korie D. Rose; Wall Street Journal, Atlanta Journal-Constitution summer interns;

Tina Turner; Senegal unrest; Rochelle Riley; abuses of journalists in Sudan; Guatemala’s José Rubén Zamora

Homepage photo: Ta-Nehisi Coates takes a “selfie” with Howard University students in 2015

Support Journal-ismsDonations are tax-deductible.

Intended Lesson Made Some ‘Uncomfortable’

A South Carolina school district shut down discussion of Ta-Nehisi Coates’ memoir “Between the World and Me,” saying it violated a state law prohibiting instruction on controversial topics related to race, Bristow Marchant reported last week for The State in Columbia, S.C.

PEN America, a century-old advocate for literary free expression, called the action “an outrageous act of government censorship.”

The opposition to discussion of Coates’ book is only the latest assault on teaching about race.

A Washington Post-Ipsos poll released Friday showed that 75 percent of Black Americans and 47 percent of white Americans were concerned about states stopping Black history from being taught in public schools.

The Miami Herald and Tampa Bay Times reported Thursday that Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis “vetoed funding for projects that promote aspects of Black history, an action that is consistent with the governor’s yearslong push to restrict how racism and other aspects of history can be taught in schools and workplaces.

“The governor eliminated $160,000 in funding for a Black History Month celebration in Orlando called the 1619 Fest, whose theme this year was to bring awareness to the health disparities Black people face in America. DeSantis also cut $200,000 in funding for Florida’s Black Music Legacy, a project designed to highlight the state’s contributions to Black music.

“Last year, DeSantis vetoed $1 million for Valencia College to create a feature film about the 1920 Ocoee Election Day Massacre, in which a white mob attacked and killed dozens of Black voters in the nation’s worst instance of Election Day violence,” Lawrence Mower, Mary Ellen Klas, Ana Ceballos and Romy Ellenbogen reported for the newspapers’ joint capital bureau.

The suppression is not new. Writing Saturday in the New York Review of Books, historian and academic Robin D.G. Kelley (pictured) told readers, “Black Studies has been under attack since its formal inception on college campuses in the late 1960s, and repression of all knowledge advancing Black freedom goes back much further. Most state laws prohibiting enslaved Africans from learning to read and write were introduced after 1829, in response first to the publication of David Walker’s Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World — an unrelenting attack on slavery and US hypocrisy for maintaining it — and then to Nat Turner’s rebellion two years later. Back then the Appeal was contraband: anyone caught with it faced imprisonment or execution. Today it is a foundational text in Black Studies.”

The suppression is not new. Writing Saturday in the New York Review of Books, historian and academic Robin D.G. Kelley (pictured) told readers, “Black Studies has been under attack since its formal inception on college campuses in the late 1960s, and repression of all knowledge advancing Black freedom goes back much further. Most state laws prohibiting enslaved Africans from learning to read and write were introduced after 1829, in response first to the publication of David Walker’s Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World — an unrelenting attack on slavery and US hypocrisy for maintaining it — and then to Nat Turner’s rebellion two years later. Back then the Appeal was contraband: anyone caught with it faced imprisonment or execution. Today it is a foundational text in Black Studies.”

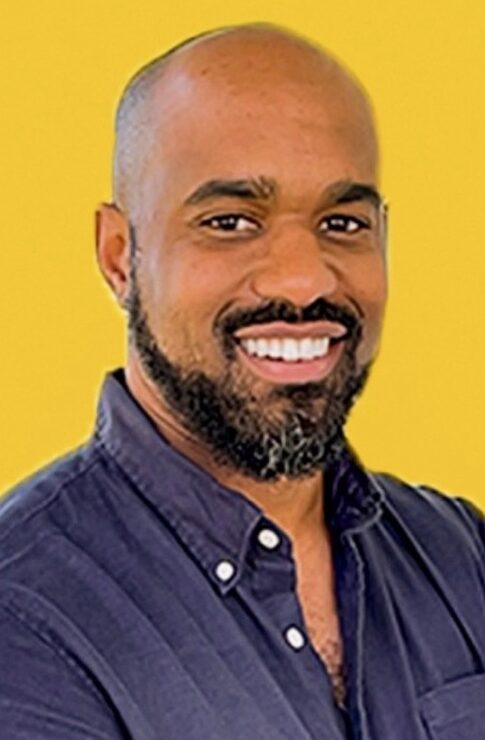

Chapin High School in Chapin, S.C., is 81 percent white but is soon to have a Black principal in Ed Davis (pictured), hired in part because of his “understanding of the Chapin community.” Students in an advanced placement language arts class were to read Coates’ best-selling 2015 memoir, which recaps American racial history and its impact on his life growing up Black in inner-city Baltimore and “was written in the form of a letter addressed to Coates’ teenaged son,” Marchant reported.

Chapin High School in Chapin, S.C., is 81 percent white but is soon to have a Black principal in Ed Davis (pictured), hired in part because of his “understanding of the Chapin community.” Students in an advanced placement language arts class were to read Coates’ best-selling 2015 memoir, which recaps American racial history and its impact on his life growing up Black in inner-city Baltimore and “was written in the form of a letter addressed to Coates’ teenaged son,” Marchant reported.

The video “Chapin: This Is Home” touts the school spirit at Chapin High School. Of its 1,592 students, 1,303 are white; 103 Hispanic; 90 Black; 30 Asian; three American Indian/Alaska Native; and one Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. Sixty-two are of two or more races, according to state statistics from 2021.

“ ‘This book is studied as part of the argument essay unit for the AP Lang exam,’ teacher Mary Wood wrote regarding the book’s inclusion in her lesson plan, one of several documents related to the class released by the Lexington-Richland 5 school district as part of a freedom of information request. Elsewhere, Wood says she taught the same book the previous year without any controversy.

“The lesson plan released as part of the documents request prompts students to analyze and respond to some of Coates’ arguments in the book. Instructions include ‘Describe Coates’ primary statement regarding identity and your position about his argument,’ ‘Describe your understanding of systemic racism,’ and ‘Do you think racism is a pervasive problem in America? Why or why not?’

“But the class didn’t get far in its assessment of the National Book Award winner, after at least some students expressed discomfort with two short videos played in class as preparation for the book: ‘The Unequal Opportunity Race’ and ‘Systemic Racism Explained.’

“ ‘Hearing (Wood’s) opinion and watching these videos made me feel uncomfortable,’ one unnamed student wrote to a school board member after the class. ‘I actually felt ashamed to be Caucasian… These videos portrayed an inaccurate description of life from past centuries that she is trying to resurface. I don’t feel as though it is right because these videos showed antiquated history. I understand in AP Lang, we are learning to develop an argument and have evidence to support it, yet this topic is too heavy to discuss.’ ”

The incident was good column material for South Carolina native Issac J. Bailey (pictured), who wrote for the Charlotte Observer, “I’ve heard similar stories from black professors in South Carolina who’ve also had white students balking at such work and got their parents to intervene. Let me be franker: If you came into my college classroom with that attitude, you’d fail, and spectacularly. I would not disrespect you. But I will challenge you, sometimes make you squirm. And I will absolutely present information you don’t like and expect you to explain it clearly and sometime provide comprehensive, well-reasoned explanations for why you agree or disagree. . . .

The incident was good column material for South Carolina native Issac J. Bailey (pictured), who wrote for the Charlotte Observer, “I’ve heard similar stories from black professors in South Carolina who’ve also had white students balking at such work and got their parents to intervene. Let me be franker: If you came into my college classroom with that attitude, you’d fail, and spectacularly. I would not disrespect you. But I will challenge you, sometimes make you squirm. And I will absolutely present information you don’t like and expect you to explain it clearly and sometime provide comprehensive, well-reasoned explanations for why you agree or disagree. . . .

“You attended a school that’s more than 80 percent white, and still, you couldn’t handle a lesson on this country’s racial history and present without crying foul. Must this country, the world, forever cater to your every whim or preference?”

Coates rose to international prominence in 2014 after The Atlantic published his “The Case for Reparations,” an extensively reported argument for why African Americans are owed a debt for the racial penalties paid since slavery. The piece “has brought more visitors to the Atlantic [website] in a single day than any single piece we’ve ever published,” Atlantic editor James Bennett said at the time.

- Minerva Canto, Los Angeles Times: Commentary: Are book bans unconstitutional? They are certainly political

- Alex Degman, WBEZ Chicago: The fine print of Illinois’ ban on book bans — Gov. JB Pritzker signed a measure that will withhold state funds from libraries that ban books. The move sparked a lot of questions.

- Sarah Jones, New York: What the Censors Want

- Will Sutton, NOLA.com: I agree with this approach to sexually explicit books. Do you? (June 6)

Blacks Expect Racism to Worsen in Their Lifetimes

“An overwhelming share of Black Americans think the U.S. economic system is stacked against them and a slim majority believe the problem of racism will worsen during their lives, according to a Washington Post-Ipsos poll that explored the attitudes of the country’s second-largest minority group,” Tim Craig, Emily Guskin and Scott Clement wrote Friday for The Washington Post.

“The poll finds that Black adults worry they are marginalized and under threat by acts of hate and discrimination in their day-to-day lives. Most also say it is more dangerous to be a Black teenager now than when they were teens.

“Nonetheless, nearly half of Black Americans say it’s also a ‘good time’ to be a Black person in the country, up from 30 percent in 2020 when the U.S. was gripped by political divisions during Donald Trump’s presidency and from 34 percent last spring after a white supremacist killed 10 Black people at a Buffalo grocery store. The poll was conducted among more than 1,200 Black adults over two weeks in late April and early May. . . .”

The survey also found, “Black Americans are uneasy over the nation’s political and cultural environment and believe most White Americans don’t trust them. Follow-up interviews with respondents show a variety of factors fueling these concerns about the future — a rise in hate groups, gun violence, and new laws in Florida and other states regulating the teaching of Black history and racism. . . .”

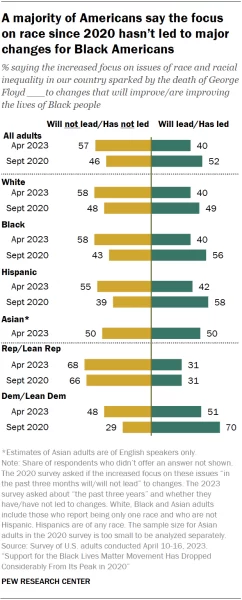

Separately, the Pew Research Center reported Wednesday, “Ten years after the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag first appeared on Twitter, about half of U.S. adults (51%) say they support the Black Lives Matter movement, according to a new Pew Research Center survey. Three years ago, following the murder of George Floyd, two-thirds expressed support for the movement.”

The Pew report, by Juliana Menasce Horowitz, Kiley Hurst and Dana Braga, also said, “81% of Black adults say they support the movement, compared with 63% of Asian adults, 61% of Hispanic adults and 42% of White adults. White adults are more likely than those in other racial and ethnic groups to describe the movement as divisive and dangerous (about four-in-ten White adults do so, compared with 30% or fewer among the other groups), and they are the least likely to describe it as empowering.”

COVID Relief Led to ‘Greatest Grift in U.S. History’

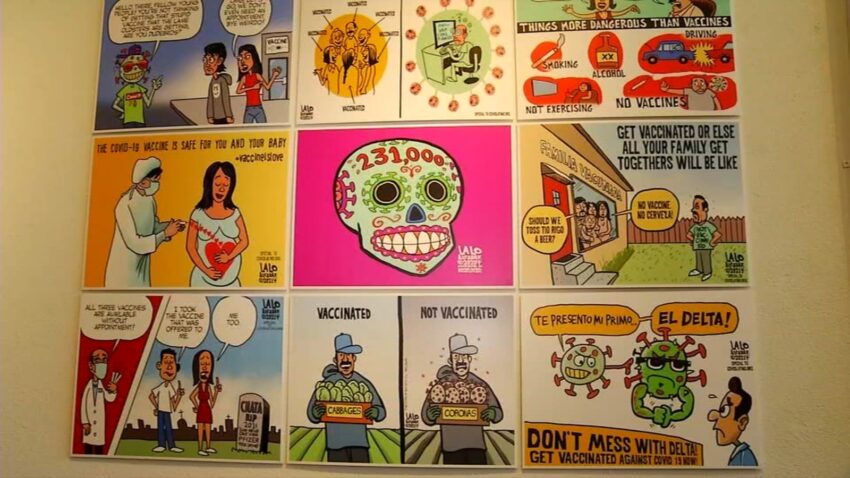

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed during the COVID pandemic that “some Black or African American people and Hispanic or Latino people are less likely to be vaccinated against COVID-19 than people in other racial and ethnic minority groups and non-Hispanic White people . . . In addition to being less likely to get a vaccine, Black or African American people and Hispanic or Latino people are more likely to get seriously ill and die from COVID-19 due to the factors listed above.”

Now the Associated Press reports that its own analysis shows that government efforts to get money to COVID’s potential victims “led to the greatest grift in U.S. history, with thieves plundering billions of dollars in federal COVID-19 relief aid intended to combat the worst pandemic in a century and to stabilize an economy in free fall.”

“Much of the theft was brazen, even simple,” the AP’s Richard Lardner, Jennifer McDermott and Aaron Kessler reported Tuesday.

“Fraudsters used the Social Security numbers of dead people and federal prisoners to get unemployment checks. Cheaters collected those benefits in multiple states. And federal loan applicants weren’t cross-checked against a Treasury Department database that would have raised red flags about sketchy borrowers.

“Criminals and gangs grabbed the money. But so did a U.S. soldier in Georgia, the pastors of a defunct church in Texas, a former state lawmaker in Missouri and a roofing contractor in Montana. . . .

“An Associated Press analysis found that fraudsters potentially stole more than $280 billion in COVID-19 relief funding; another $123 billion was wasted or misspent. Combined, the loss represents 10% of the $4.2 trillion the U.S. government has so far disbursed in COVID relief aid.

“That number is certain to grow as investigators dig deeper into thousands of potential schemes.

“How could so much be stolen? Investigators and outside experts say the government, in seeking to quickly spend trillions in relief aid, conducted too little oversight during the pandemic’s early stages and instituted too few restrictions on applicants. In short, they say, the grift was just way too easy. . . .”

- Mark Brodie, KJZZ-FM, Phoenix: Cartoonist Lalo Alcaraz reflects on how 3 years of COVID-19 changed us (March 21)

- Gary Lee, Oklahoma Eagle: Students of the COVID-19 Era: How the Pandemic followed them to Langston University, Oklahoma’s only HBCU (April 20)

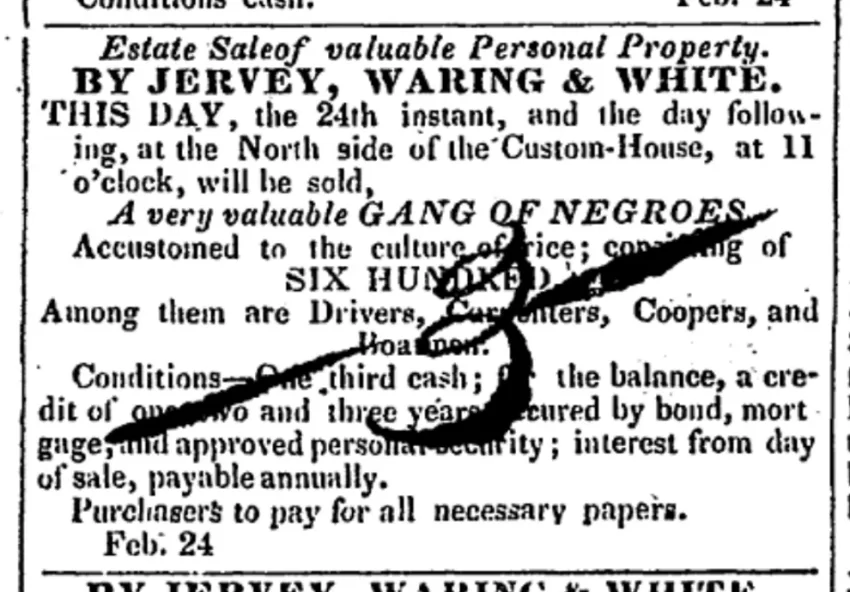

What a Story! Largest Known U.S. Slave Auction

“Sitting at her bedroom desk, nursing a cup of coffee on a quiet Tuesday morning, Lauren Davila scoured digitized old newspapers for slave auction ads,” Jennifer Berry Hawes reported Friday for ProPublica. “A graduate history student at the College of Charleston, she logged them on a spreadsheet for an internship assignment. It was often tedious work.”

The story, which carried the headline, “How a Grad Student Uncovered the Largest Known Slave Auction in the U.S.,” also touches on the role that newspapers played in aiding the slavocracy. It continues:

“She clicked on Feb. 24, 1835, another in a litany of days on which slave trading fueled her home city of Charleston, South Carolina. But on this day, buried in a sea of classified ads for sales of everything from fruit knives and candlesticks to enslaved human beings, Davila made a shocking discovery.

“On page 3, fifth column over, 10th advertisement down, she read:

“ ‘This day, the 24th instant, and the day following, at the North Side of the Custom-House, at 11 o’clock, will be sold, a very valuable GANG OF NEGROES, accustomed to the culture of rice; consisting of SIX HUNDRED.’

“She stared at the number: 600.

“A sale of 600 people would mark a grim new record — by far. . . .

“A ProPublica reporter found the original ad for the sale, which ran more than two weeks before the one Davila spotted. Published on Feb. 6, 1835, it revealed that the sale of 600 people was part of the estate auction for John Ball Jr., scion of a slave-owning planter regime. Ball had died the previous year, and now five of his plantations were listed for sale — along with the people enslaved on them.

“The Ball family might not be a household name outside of South Carolina, but it is widely known within the state thanks to a descendant named Edward Ball who wrote a bestselling book in 1998 that bared the family’s skeletons — and, with them, those of other Southern slave owners.

“ ‘Slaves in the Family’ drew considerable acclaim outside of Charleston, including a National Book Award . . .”

The story goes on to detail what happened to the slave owners and the enslaved, and the many businesses and individuals who profited from this trafficking of African Americans.

A ‘”stark reminder of how America’s entrenched racial wealth gap was born, Davila said, with repercussions still felt today,” Berry Hawes concluded.

- John Blake, CNN: As the nation celebrates Juneteenth, it’s time to get rid of these three myths about slavery

- Erin Blakemore, National Geographic: How two centuries of slave revolts shaped American history (Nov. 8, 2019)

- Antoine Davis and Darrell Jackson, History News Network: What to the Incarcerated Is Juneteenth?

- Kelly Glass, stacker.com: 10 notable Juneteenth celebrations across the US

- Amy Goodman and Denis Moynihan, “Democracy Now!”: Celebrate Juneteenth, but Racism Still Kills

- Renee Graham, Boston Globe: The gentrification of Juneteenth

- Peniel E. Joseph, Texas Monthly: The Story We’ve Been Told About Juneteenth Is Wrong

- Tiya Miles, New York Times: As Juneteenth Goes National, We Must Preserve the Local

- Donna M. Owens, Baltimore Sun: Marking a Maryland legacy in Freetown, where freedom arrived before Juneteenth

- Khaleda Rahman, Newsweek: Juneteenth to Be Ignored by Majority of Americans

- Esther Schrader, Southern Poverty Law Center: Activists Protest Confederate Monuments With Virtual Black History Memorials

- William Spivey, Medium: The Juneteenth Federal Holiday Only Exists Because Of The George Floyd Protests

- Alicia M. Walters and Collette Watson, Time: This Juneteenth, We Must Undo the Toxic Narratives Placed on Black People

- Julian Wyllie, Current: ‘Keyshawn Solves It’ podcast threads Juneteenth history into stories that promote critical thinking skills

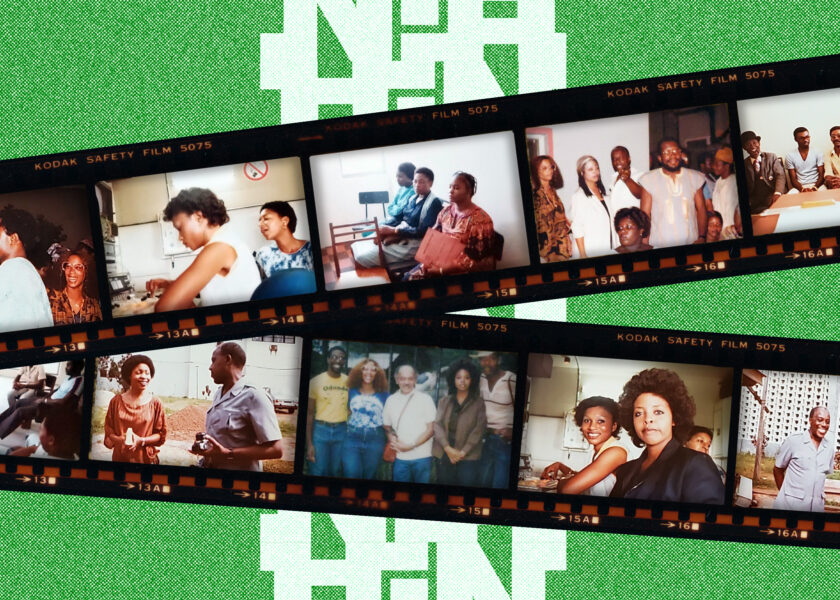

Progress on Making Ebony, Jet Photo Archives Public

After Johnson Publishing Co. filed for bankruptcy in 2019, a consortium comprising five institutions including the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Smithsonian Institution purchased the archive, the repository of much of the documented photographic history of Black America in the late 20th century, as recorded by Ebony and Jet magazines.

“Getty committed $30 million in support of the processing and digitization of the archive, which will make the collection available to scholars, journalists, and the general public like it never has before,” Erin Migdol wrote June 1 for Getty.

“Last year, ownership of the archive was officially transferred to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) and Getty.

Steven Booth is Getty Research Institute’s Johnson Publishing Company archive manager. “This fall, Booth and his team of seven archivists will begin cataloging the collection and sending it to the Smithsonian’s storage facility in batches of a few thousand images at a time,” Migdol continued.

“A Smithsonian team will take the images, digitize them, and make them available online. Getty will use those images and the metadata created by the archivists to build a website that enables access to the collection, and aims to augment it using computer vision to provide enhanced searchability over time. Once there’s a critical mass of material, the site will be made public and then those eager to see the JPC collection can look forward to periodic additions of images to the website for about the next five years.

“After that, the Smithsonian will be the official stewards of the physical archive in Washington, DC, though the archive will remain available to Getty (and other interested institutions) for research and exhibition. Meanwhile, both institutions will engage in outreach efforts to expose new audiences to the JPC archive. Starting in July 2023, the two institutions are organizing a series of workshops aimed at introducing undergraduate students from historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) to conservation as a potential career path, using the JPC archive to teach principles of photographs conservation. The 2023 workshop will be hosted at the Block Museum of Art at Northwestern University. . . .”

Stanley Terrell, Newark Journalist, Dies at 74

Stanley Terrell, who worked at the Star-Ledger in Newark, N.J., for 38 years, died June 8 after battling cancer. He was a reporter, columnist, editorial writer and native of the city who was a voice of the Black community at the newspaper. Terrell turned 74 on Feb. 16.

“I participated in every genre of writing that goes into the pages, from feature stories to hard news and opinion columns,” Terrell wrote on his LinkedIn page. “Also edited not only news copy, but reviews and in-house columnists.”

At a 2021 forum at Rutgers University — Newark, Terrell spoke of “his early fights to bring the paper’s usage standards up-to-date, particularly in the eyes of its black readers,” according to an account for the school by Andaiye Taylor. ” ‘I fought to stop them from saying ‘Negro’,” he said. ‘They continued to call Baraka LeRoi Jones,’ he added, referring to Newark native and poet Amiri Baraka.“

Bob Braun, who spent 50 years at the newspaper, called Terrell a hero of a 1971 uprising at Rahway State Prison. On Nov. 24, some 500 inmates held six hostages, including the warden, for 24 hours, Greg Hatala later reported for NJ Advance Media.

“Six officers were injured, three with stab wounds. The [inmates’] demands included a better diet, improvements in educational and vocation training, better discipline of officers and additional medical supplies including aspirin.”

At one point, three reporters — Terrell, Carl Zeitz of the Associated Press and John Needham of United Press International — were led into the cell block, David K. Shipler reported for The New York Times.

“ ‘The negotiations almost broke down right then,’ Mr. Zeitz said later. Inmates shouted that they wanted guards and troopers out of the cellblock. The reporters were led out, then led back in, Mr. Zeitz said. The demands were received, and the remaining hostages freed.”

Terrell joined the Star-Ledger in 1968 and brought to the newspaper the too-rare perspective of a Black Newark native. He was not the first Black reporter at the paper, as he was sometimes described — that distinction goes to Ernest Johnston Jr., who worked at the paper in the mid-1960s, including during the uprising of 1967 where at least 26 died — but Terrell knew the city inside and out. “His column ‘Newark This Week’ battles city issues from education to healthcare that have been present since the days of the riot,” wrote Kimberly Siegal, who interviewed Terrell for a paper in 2006 while a student at the University of Pennsylvania.

The second of four children of Wilda and Millard E. Terrell, Terrell told Siegal that his family members “were not wealthy individuals but fared well compared to other public housing residents. ‘We were poor,’ Terrell remembers, ‘but the housing was adequate. It wasn’t run down; it wasn’t like the images you have of public housing.’ “

Terrell’s recounting of his childhood experiences with police might sound familiar: “You know we had to give [the police] grudging respect because they could lock you up and they could beat you. But when they came it was like, oh boy. They never came when you needed something. . . .

“I won’t exaggerate; 7 out of 10 times you walk away with a bad taste in your mouth after you have a confrontation with the police. It didn’t have to be you confronting them, you just had to be in their presence and watching them conduct themselves as related to your community and it was always negative.”

Siegal added that Terrell describes a riot as “an explosion of frustration; it’s something that comes about after a long period of time.” After Newark’s 1967 uprising, “he made a pact with himself never to leave his home city.”

Terrell wrote poems, short stories and freelance pieces after retiring from the Star-Ledger in 2006.

On Facebook, Terrell’s friend Glenda R. Mattox wrote that Terrell “illuminated our hometown with his brilliant articles in the Newark Star-Ledger and in his book of short stories, ‘Brickettes.’ I clearly remember the evening I met him: 2.11.1965. I was 12 years-old. Easy-going, fun-loving, fascinatingly witty, extremely generous; it was always so good to run into Stan walking around the town he loved so much. It was something he knew inside and out; and it was my blessing and my pleasure to have known him. Rest In Peace, Stan. You fought the good fight on all fronts.”

A memorial service is planned for 1 p.m. Friday, June 23, at the Whigham Funeral Home, 580 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd., Newark, NJ 07102; phone (973) 622-6872.

Short Takes

- “In the eighties, a group of Black American journalists went to Nigeria to train reporters and escape the racism they’d encountered in their newsrooms. The trip did not go as planned,” Feven Merid wrote Feb. 22 for Columbia Journalism Review, a piece still featured on the CJR website. Among those involved in the company they formed, Jacaranda Nigeria Limited, were Barbara Lamont, a reporter at CBS News Radio; Randy Daniels, CBS correspondent in South Africa; Adam Clayton Powell III, a producer for the CBS morning news and Kelley Chunn, who worked at Boston’s WBZ-TV. They discovered that Nigerians viewed them more as Westerners than as fellow Black people, and “at times it seemed as though their training was doing less to improve the strength of Nigeria’s journalism than to bolster the quality” of government propaganda. However, with the new perspective gained from the experience and the encouragement of CBS correspondent Ed Bradley, Lamont eventually bought WCCL-TV in New Orleans.

-

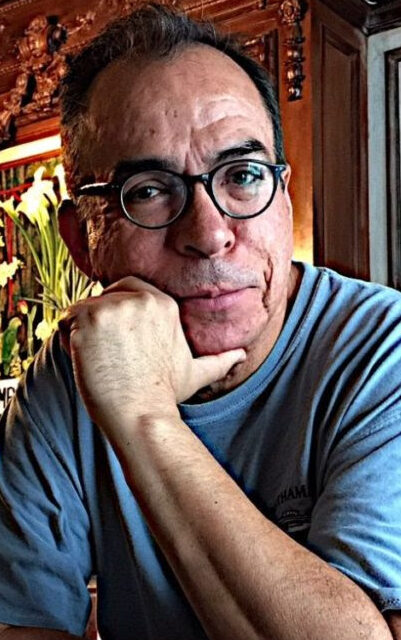

Alfredo Corchado (pictured), Mexico bureau chief for the Dallas Morning News; Angela Kocherga, news director at KTEP, a public radio station in El Paso, Texas; Lori Montenegro, Noticias Telemundo D.C. bureau chief; and Enrique Flor Zapler, investigative reporter at El Nuevo Herald, are to be inducted into the Hall of Fame of the National Association of Hispanic Journalists at the organization’s convention gala July 15, NAHJ announced Friday. Zapler is being inducted posthumously.

Alfredo Corchado (pictured), Mexico bureau chief for the Dallas Morning News; Angela Kocherga, news director at KTEP, a public radio station in El Paso, Texas; Lori Montenegro, Noticias Telemundo D.C. bureau chief; and Enrique Flor Zapler, investigative reporter at El Nuevo Herald, are to be inducted into the Hall of Fame of the National Association of Hispanic Journalists at the organization’s convention gala July 15, NAHJ announced Friday. Zapler is being inducted posthumously.

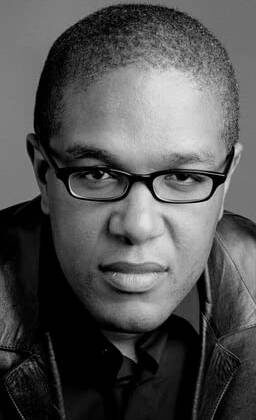

Christopher Farley (pictured), executive editor at Amazon Inc.’s Audible and formerly senior editor for The Wall Street Journal and music critic for Time magazine, has been named senior director, arts programming and development for PBS, the network announced May 30. “In this role, Farley will oversee the development and production of a multiplatform strategy focused on arts, performance, culture, and lifestyle content. . . . Farley also served as a consulting producer on the Peabody-winning HBO documentary ‘Mr. Dynamite: The Rise of James Brown.’ As a consulting producer for ‘Afrofuturism: A History of Black Futures’ at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, Farley was part of a team that aimed to help show how science fiction and imaginative storytelling can serve as the inspiration for real cultural change. . . . “

Christopher Farley (pictured), executive editor at Amazon Inc.’s Audible and formerly senior editor for The Wall Street Journal and music critic for Time magazine, has been named senior director, arts programming and development for PBS, the network announced May 30. “In this role, Farley will oversee the development and production of a multiplatform strategy focused on arts, performance, culture, and lifestyle content. . . . Farley also served as a consulting producer on the Peabody-winning HBO documentary ‘Mr. Dynamite: The Rise of James Brown.’ As a consulting producer for ‘Afrofuturism: A History of Black Futures’ at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, Farley was part of a team that aimed to help show how science fiction and imaginative storytelling can serve as the inspiration for real cultural change. . . . “

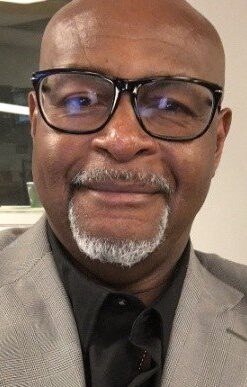

Veteran news manager John X. Miller (pictured), named in March 2022 as the Dallas Morning News’ senior editor working with business, features and sports teams, is “taking a break from the daily grind to pursue several projects that I have a heart for, including two websites that I’ve started and forming a quartet,” Miller announced June 12 on Facebook (video). “That’s right, an R&B, soul & jazz group. God’s blessed me with a dynamic singing voice and I’m using it before I lose it. BTW: I’m not leaving journalism; I’m still chair of the Maynard Institute board & consulting is in my future as well.” Miller’s wife, Alison Bethel, “and I have already moved from Dallas to Florida, closer to her family and roots in South Florida. It’s time to slow down some and count my blessings.” Miller also told Journal-isms that “there’s so much to be done away from daily journalism that supports the people who do it.”

Veteran news manager John X. Miller (pictured), named in March 2022 as the Dallas Morning News’ senior editor working with business, features and sports teams, is “taking a break from the daily grind to pursue several projects that I have a heart for, including two websites that I’ve started and forming a quartet,” Miller announced June 12 on Facebook (video). “That’s right, an R&B, soul & jazz group. God’s blessed me with a dynamic singing voice and I’m using it before I lose it. BTW: I’m not leaving journalism; I’m still chair of the Maynard Institute board & consulting is in my future as well.” Miller’s wife, Alison Bethel, “and I have already moved from Dallas to Florida, closer to her family and roots in South Florida. It’s time to slow down some and count my blessings.” Miller also told Journal-isms that “there’s so much to be done away from daily journalism that supports the people who do it.”

“President Joe Biden has tapped Michael Tyler, a seasoned Democratic strategist, to serve as his campaign communications director, his campaign announced Thursday,” CNN reported Thursday. “Tyler previously served as deputy communications director on Sen. Cory Booker’s 2020 campaign and as spokesman and chief of staff to former chairman of the Democratic National Committee Tom Perez. Tyler is set to officially join the campaign in July. . . .”

“President Joe Biden has tapped Michael Tyler, a seasoned Democratic strategist, to serve as his campaign communications director, his campaign announced Thursday,” CNN reported Thursday. “Tyler previously served as deputy communications director on Sen. Cory Booker’s 2020 campaign and as spokesman and chief of staff to former chairman of the Democratic National Committee Tom Perez. Tyler is set to officially join the campaign in July. . . .”

- “The Harlem-based national media arts nonprofit Black Public Media (BPM) has received a $40,000 award from the National Endowment for the Arts’ Grants for Arts Projects program,” BPM announced Thursday. “The award will support its fellowship and residency program for new works in immersive, interactive and emerging media at the Johnny Carson Center for Emerging Media Arts at the University of Nebraska Lincoln. The initiative is a part of BPMplus, Black Public Media’s program designed to increase Black participation in emerging tech storytelling, which was founded in 2018. . . . “

- “Pat Robertson, the American televangelist who described natural disasters that decimated New Orleans and Haiti [as] God’s vengeance on the victims, died this month at 93. Following his death, the US media has largely fastened its eyes on the long shadow he cast on American politics,” Alex Park wrote for Africa Is a Country. Park added, “as poisonous as his influence was on American politics, Robertson left a far more cynical legacy in Africa. In 1991, people in Kinshasa, Congo began demonstrating, often violently, calling for the nation’s dictator, Mobutu Sese Seko, to step down. Mobutu came to power with the help of the United States government. But as the Cold War slid to a halt, his allies in Washington became less interested in taking his phone calls. So he sought out new ones, and he found one in Pat Robertson. . . .”

Caitlin Dickerson of The Atlantic is one of three winners of the Livingston Awards bestowed by the University of Michigan’s Wallace House Center for Journalists. They honor stories that “represent the best in local, national and international reporting by journalists under the age of 35.” Dickerson, 33, won for “We Need to Take Away Children,” “a masterful examination of the U.S. government’s child separation policy revealing how officials at every level heedlessly and often deceptively advanced policy that defied the country’s most basic stated values.” The piece also won a Pulitzer Prize this year for explanatory writing. Winners in the other categories were Anna Wolfe, 28, of Mississippi Today and Vasilisa Stepanenko, 22, of The Associated Press.

Caitlin Dickerson of The Atlantic is one of three winners of the Livingston Awards bestowed by the University of Michigan’s Wallace House Center for Journalists. They honor stories that “represent the best in local, national and international reporting by journalists under the age of 35.” Dickerson, 33, won for “We Need to Take Away Children,” “a masterful examination of the U.S. government’s child separation policy revealing how officials at every level heedlessly and often deceptively advanced policy that defied the country’s most basic stated values.” The piece also won a Pulitzer Prize this year for explanatory writing. Winners in the other categories were Anna Wolfe, 28, of Mississippi Today and Vasilisa Stepanenko, 22, of The Associated Press.

Digital journalist Korie D. Rose, 37 (pictured), a video editor at WJLA-TV in Washington who was found dead in his Hyattsville, Md., home on Jan. 20, died of atheroscleotic and hypertensive cardiovascular disease, with recent illness and renal transplant contributing factors, the Maryland Department of Health has determined. The Washington Association of Black Journalists presented its newly created Korie D. Rose Award for Excellence June 10 to high school student Sheridan Lee at the end of WABJ’s annual eight-week Urban Journalism Workshop. “Organizers explained that Korie participated in the workshop several years ago and came back to become a mentor,” WJLA reported. “Korie was described as ‘a dedicated mentor to students in the workshop for many years.’ “

Digital journalist Korie D. Rose, 37 (pictured), a video editor at WJLA-TV in Washington who was found dead in his Hyattsville, Md., home on Jan. 20, died of atheroscleotic and hypertensive cardiovascular disease, with recent illness and renal transplant contributing factors, the Maryland Department of Health has determined. The Washington Association of Black Journalists presented its newly created Korie D. Rose Award for Excellence June 10 to high school student Sheridan Lee at the end of WABJ’s annual eight-week Urban Journalism Workshop. “Organizers explained that Korie participated in the workshop several years ago and came back to become a mentor,” WJLA reported. “Korie was described as ‘a dedicated mentor to students in the workshop for many years.’ “

- The Wall Street Journal (top photo) and the Atlanta Journal-Constitution (bottom) are among news organizations announcing their summer internship classes. “Our summer interns have embarked on their journey with The Wall Street Journal!” Aisha Al-Muslim wrote last week for Medium. “This talented group of 29 journalists will be working for 10 weeks across all of our platforms, including print, wires, WSJ.com, audio, video, photo, graphics and social media. They will be working from bureaus across the U.S., as well as London, Tokyo and Beijing.” At the AJC, the interns “represent the company’s commitment to developing young, diverse journalists who will continue our mission to deliver the highest level of journalism to our community,” Todd C. Duncan wrote Wednesday.

- The Tina Turner story continues to inspire good reads. Examples: On June 6, Andscape published a 5,000-word piece by Soraya Nadia McDonald that asserts, “By the time she published her 2018 autobiography, Tina Turner: My Love Story, Turner’s tale of her life boasts such clarity that it’s impossible not to see how she, her parents, her children, and her first husband were shaped by the white supremacy permeating American life. Indeed, My Love Story often shares the vocabulary and form of a first-person slave narrative.” In the Oklahoma Eagle, part of the Black press, managing editor and veteran journalist Gary Lee quoted North Tulsans saying they felt Turner to be one of them. Lee told of being at the Opera Ball at the vaunted Baur au Lac Hotel on Lake Zurich, Switzerland, when dance partners changed from one to the next, “and at one point, I found myself dancing with the queen of rock and roll,” leaving him starstruck. For Al Jazeera, Chelsi West Ohueri answered the question, “How did Tina Turner become an unlikely icon in Albania?” Turner died May 24 at 83.

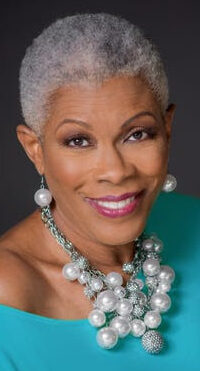

A journalism school was ransacked, a TV channel was suspended for 30 days and restrictions on access to the Internet and social media were imposed amid political unrest and violence in Senegal, a west African country normally immune from such disruption. “The cutting of Walf TV’s signal occurred as it was broadcasting the demonstrations that followed the sentencing of opposition leader, Ousmane Sonko to two years imprisonment,” the International Federation of Journalists said on June 15. Reporters Without Borders warned June 1 that the unrest “must not be used as grounds for restricting the right to report the news.” Meanwhile, in the United States, journalist Rochelle Riley (pictured) wrote a well-crafted column for the Detroit Free Press describing how she came to discover she had roots in Senegal. It was headlined, “I’m not sure where my ancestors were from. But I know where I belong.”

A journalism school was ransacked, a TV channel was suspended for 30 days and restrictions on access to the Internet and social media were imposed amid political unrest and violence in Senegal, a west African country normally immune from such disruption. “The cutting of Walf TV’s signal occurred as it was broadcasting the demonstrations that followed the sentencing of opposition leader, Ousmane Sonko to two years imprisonment,” the International Federation of Journalists said on June 15. Reporters Without Borders warned June 1 that the unrest “must not be used as grounds for restricting the right to report the news.” Meanwhile, in the United States, journalist Rochelle Riley (pictured) wrote a well-crafted column for the Detroit Free Press describing how she came to discover she had roots in Senegal. It was headlined, “I’m not sure where my ancestors were from. But I know where I belong.”

- Dozens of journalists faced abuses during the civil war in Sudan, including threats of detention, according to Mohamed Abdelaziz, secretary of the Sudanese Journalists Syndicate, reports Radio Dabanga, an independent, Sudanese news and information broadcaster. More than 40 violations were documented in the second half of May, Radio Dabanga reported the previous week, including enforced disappearances and raids. “Balanced and objective coverage of the events is not benefitting either side of the fighting, and dozens of journalists were therefore threatened and detained,” the secretary said.

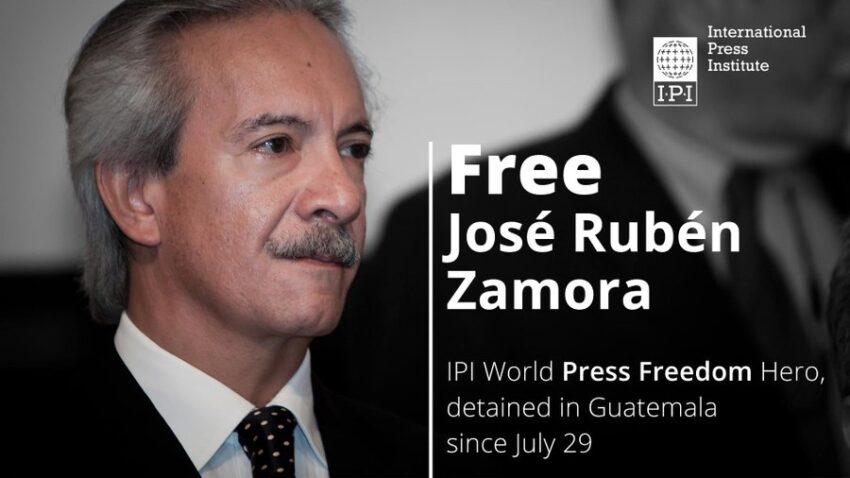

- “One of Guatemala’s most high-profile journalists was convicted on Wednesday of money laundering and sentenced to up to six years in prison, in a trial denounced by human rights and free speech advocates as another sign of the deteriorating rule of law,” Emiliano Rodríguez Mega and Jody García reported Wednesday, updated Thursday, for The New York Times. “The journalist, José Rubén Zamora, was tried on charges of financial wrongdoing that prosecutors say focused on his business dealing, not his journalism. He was acquitted of blackmail and influence peddling, and fined about $40,000. . . .”

- The Guatemala story was covered extensively Tuesday by the progressive radio and television show “Democracy Now!” which asked Guatemalan journalist José Carlos Zamora, “What has happened in recent years that allowed this resurgence of this right-wing government in your country?” Journal-isms asked “Democracy Now!” if it could point to similar coverage of outrages against the press by left-wing governments in Latin America, such as Nicaragua or Cuba. The program did not respond.

To subscribe at no cost, please send an email to journal-isms+subscribe@groups.io and say who you are.

Facebook users: “Like” “Richard Prince’s Journal-isms” on Facebook.

Follow Richard Prince on Twitter @princeeditor

Richard Prince’s Journal-isms originates from Washington. It began in print before most of us knew what the internet was, and it would like to be referred to as a “column.” Any views expressed in the column are those of the person or organization quoted and not those of any other entity. Send tips, comments and concerns to Richard Prince at journal-isms+owner@

View previous columns (after Feb. 13, 2016).

View previous columns (before Feb. 13, 2016)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2018 (Jan. 4, 2019)

- Book Notes: Is Taking a Knee Really All That? (Dec. 20, 2018)

- Book Notes: Challenging ’45’ and Proudly Telling the Story (Dec. 18, 2018)

- Book Notes: Get Down With the Legends! (Dec. 11, 2018)

- Journalist Richard Prince w/Joe Madison (Sirius XM, April 18, 2018) (podcast)

- Richard Prince (journalist) (Wikipedia entry)

- February 2018 Podcast: Richard “Dick” Prince on the need for newsroom diversity (Gabriel Greschler, Student Press Law Center, Feb. 26, 2018)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2017 — Where Will They Take Us in the Year Ahead?

- Book Notes: Best Sellers, Uncovered Treasures, Overlooked History (Dec. 19, 2017)

- An advocate for diversity in the media is still pressing for representation, (Courtland Milloy, Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2017)

- Morgan Global Journalism Review: Journal-isms Journeys On (Aug. 31, 2017)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2016

- Book Notes: 16 Writers Dish About ‘Chelle,’ the First Lady

- Book Notes: From Coretta to Barack, and in Search of the Godfather

- Journal-isms’ Richard Prince Wants Your Ideas (FishbowlDC, Feb. 26, 2016)

- “JOURNAL-ISMS” IS LATEST TO BEAR BRUNT OF INDUSTRY’S ECONOMIC WOES (Feb. 19, 2016)

- Richard Prince with Charlayne Hunter-Gault, “PBS NewsHour,” “What stagnant diversity means for America’s newsrooms” (Dec. 15, 2015)

- Book Notes: Journalists Follow Their Passions

- Book Notes: Journalists Who Rocked Their World

- Book Notes: Hands Up! Read This!

- Book Notes: New Cosby Bio Looks Like a Best-Seller

- Journo-diversity advocate turns attention to Ezra Klein project (Erik Wemple, Washington Post, March 5, 2014)