Hate Crimes Part of a Pattern of Long Standing

[btnsx id=”5768″]

Michael B. Jordan as lawyer Bryan Stevenson, left, and Jamie Foxx as inmate Walter McMillan in “Just Mercy.” (Credit: Warner Bros.)

Hate Crimes Part of a Pattern of Long Standing

Two new civil rights thrillers — one in print, the other on the screen — can tell us much about the press, and you don’t have to look far to find the lessons.

“Just Mercy“ (watch the trailer), the story of activist black lawyer Bryan Stevenson’s efforts to free an innocent black man serving time for the 1986 murder of a white woman in Alabama, opened around the country over the weekend after an Oscar-qualifying limited release on Christmas. It was nominated for an Academy Award Monday for best adapted screenplay.

Near the end, Stevenson’s white female assistant (played by Brie Larson) at the Equal Justice Initiative, the organization he founded, tells him that she was taught that lawyers should not become too personally invested in their clients, but Stevenson’s example (he’s played by Michael B. Jordan) has shown her otherwise.

Veteran Mississippi investigative journalist Jerry Mitchell (pictured; photo by James Patterson) bears out her conclusion in “Race Against Time: A Reporter Reopens the Unsolved Murder Cases of the Civil Rights Era,” his new book to be officially published Feb. 4.

Veteran Mississippi investigative journalist Jerry Mitchell (pictured; photo by James Patterson) bears out her conclusion in “Race Against Time: A Reporter Reopens the Unsolved Murder Cases of the Civil Rights Era,” his new book to be officially published Feb. 4.

A white journalist who worked for more than three decades at the Clarion-Ledger in Jackson, Miss., and was a 2009 MacArthur “genius grant” Fellow and a 2006 Pulitzer Prize finalist, Mitchell demonstrates with his own dogged example how much a commitment to uncovering the truth can produce results, even if disappointment is sometimes part of the package. He left the Clarion-Ledger last year to found the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting.

Too few of us are familiar with the extent of the pervasive racist corruption that took place in Alabama, Mississippi and points east, west and north that cost black people their lives. Stevenson points out what fertile territory this is for the press. This is not just a matter of the past, he said at a gala showing of the film Saturday at the National Museum of African American History and Culture. He offered his view of the big picture.

“We’ve gone from 200,000 people in our prisons in 1972 to 2.2 million people in our prisons today,” Stevenson said. “There are 6 million people on probation or parole. There are 70 million Americans with [criminal records], which means that when they try to get jobs, when they try to get loans, they’re often disfavored by that arrest history.”

His questioner, Harvard scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr., remarked, “70 million!” and asked Stevenson to repeat the figures. “I want everybody to hear them.”

Stevenson replied, “The Bureau of Justice in 2002 projected that 1 in 3 black male babies born in this country is expected to go to prison, and the outrage is that nobody talked about it. There were no special commissions, there were no task forces. We didn’t get together to deal with this crisis, and that has led us to this place. You know, I go into these communities and I sit down with 11- and 12-year-old kids, and they frequently tell me that they don’t expect to be free by the time they’re 21 because all they see is their friends and their neighbors, their brothers, their cousins being caught up by this system.” That’s in large part because of the War on Drugs, mass incarceration and three-strikes laws.

“So we cannot disconnect what we are living through with mass incarceration. And today, from this commitment to using criminality as a mechanism for continuing to have control.”

To Stevenson, the underlying issue is the narrative of people of color as criminals that has persisted throughout American history.

“We need to talk about the fact that we’re a post-genocide society. I think what happened to Native people, when Europeans came to this continent, was a genocide. We killed millions of Native people, through famine and war and disease.

“But we didn’t acknowledge it as genocide. We created a narrative instead, when we said ‘those Native people, they’re savages. And we used that rhetoric to become indifferent to their suffering. . . .”

In “Racing Against Time,” Mitchell writes in his epilogue, “Truth rules. This has been a guiding principle of mine throughout my career. Truth rules, while hate thrives on obfuscation, murkiness, and fear. I’ve been told time and again to let the past be. But I have long found that a true account of a painful past does more good than murky optimism. In our current fight against a new wave of white supremacists, a clear memory is important.”

The news media haven’t always been part of the solution. Witness the apologies that Southern newspapers have had to make for their roles in fanning Jim Crow and resistance to integration.

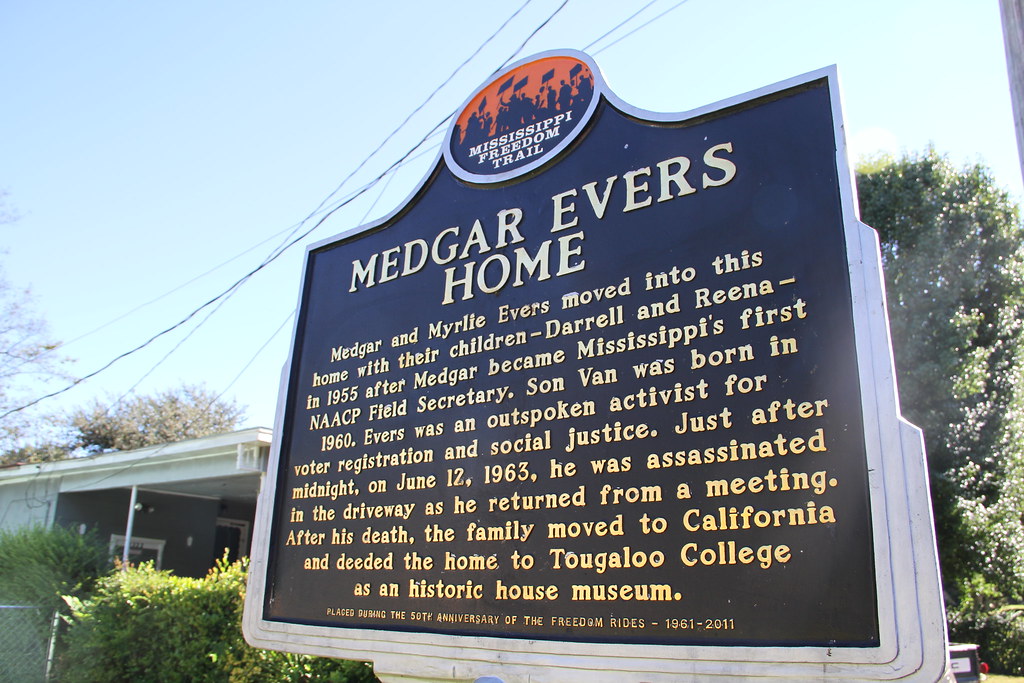

Mitchell’s former newspaper, the Clarion-Ledger, published his work uncovering the murderous activities of the Ku Klux Klan and others involved in the cold cases he’s investigated, but under prior ownership the newspaper was part of the problem. True, Bennie Ivory, a black journalist who retired in 2013 as the Clarion-Ledger’s executive editor (scroll down) is credited with supporting the work of Mitchell and others in uncovering the conspiracy to kill civil rights icon Medgar Evers. Evers’ Jackson, Miss., home is now an historic landmark (pictured).

Mitchell’s former newspaper, the Clarion-Ledger, published his work uncovering the murderous activities of the Ku Klux Klan and others involved in the cold cases he’s investigated, but under prior ownership the newspaper was part of the problem. True, Bennie Ivory, a black journalist who retired in 2013 as the Clarion-Ledger’s executive editor (scroll down) is credited with supporting the work of Mitchell and others in uncovering the conspiracy to kill civil rights icon Medgar Evers. Evers’ Jackson, Miss., home is now an historic landmark (pictured).

But on June 12,1963, “on the day of Evers’ death, the Jackson Daily News wrote that the bullet that killed him landed next to a watermelon on the kitchen counter — a cutting racist reference amid tragedy,” Mitchell writes.

He went on, “Bill Minor told me the Hedermans, a teetotaling Baptist family that owned the two newspapers, had a powerful say in state government and also backed the [white] Citizens’ Councils.

“The papers, he said, were among the worst in the nation. The editor of the Jackson Daily News, Jimmy Ward, referred to black civil rights workers as ‘chimpanzees’ in his columns, and on the same day that many newspapers featured the March on Washington and Martin Luther King Jr.’s ‘I Have a Dream’ speech on August 28, 1963, The Clarion-Ledger printed the headline, ‘Washington Is Clean Again with Negro Trash Removed.'”

Nor did the black press have completely clean hands. “To ensure help from the African-American press,” Mitchell writes, the segregation-promoting Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission “put a few black editors on the payroll, including Percy Greene, who operated the Jackson Advocate. At the commission’s request, he printed a Sovereignty Commission story verbatim, linking Martin Luther King Jr. to communists.”

The local press in Monroe, Ala., published inflammatory lies about Walter McMillan, the innocent black man portrayed by Jamie Foxx in “Just Mercy,” Stevenson writes in the 2014 book on which the movie was based, “Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption.”

However, the book and movie credit CBS-TV’s “60 Minutes” 1992 story on the case, reported by Ed Bradley and his producer colleagues, as a turning point.

But even that was a risk. “My general attitude was that press coverage rarely helped our clients. . . .,” Stevenson wrote. “I knew of too many cases where a favorable profile in the media had provoked an expedited execution date or retaliatory mistreatment that made things much worse.”

The University of North Carolina last year found a net loss of almost 1,800 local newspapers since 2004.

In 2018, the FBI showed the highest levels of violent hate crimes since 2001, in a report that the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights says underestimates the problem.

Mitchell concludes in his book’s epilogue, “We must remember the past waves of white supremacy and the myths they spread. We must remember the many innocent African-Americans and activists the Klan killed.

“We must remember what civil rights activists like Medgar Evers fought for — American values as simple as equality and the right to vote. And we must remember what they fought through — the intimidation and violence, the death threats eventually made real. We must remember, to point our compass toward justice.

“We must remember, and then act.””

- Tre’vell Anderson, Los Angeles Times: Michael B. Jordan teams with Warner Bros. to launch policy on studio diversity and inclusion (Sept. 5, 2018)

- Mike Cason, al.com: Bryan Stevenson hopes to use ‘Just Mercy’ platform to promote reforms

- Matthew Dessem, Slate: What’s Fact and What’s Fiction in Just Mercy

- Dominique Hall, Nevada Today, University of Nevada, Reno: Condemning hate and bias with student journalism

- Fred Hiatt, Washington Post: Yes, white supremacists are emboldened. But that’s not the whole story in America today. (May 5, 2019)

- David J. Krajicek, John Jay College of Criminal Justice: “The Media’s Role in Wrongful Convictions” [PDF] (2014)

- Native American Journalists Assocition: The Native American Journalists Association and Report for America take new steps to strengthen reporting in Indigenous communities

- Ruben Navarrette Jr., Washington Post Writers Group: A New Year’s resolution for America: An attack on one group is an attack on us all

- Deborah Potter, LinkedIn: What journalism jobs are going to grow?

- Martha Quillin, News & Observer, Raleigh, N.C.: It’s a notorious racist incident from NC’s past. New book explains its origins, effects.

- Sara Rafsky, Columbia Journalism Review: Media Mecca or News Desert? Covering local news in New York City

- Sara Rafsky, Columbia Journalism Review: Does the media capital of the world have news deserts?

- Mark Joseph Stern, Slate: Florida Republicans’ Voter Suppression Scheme May Backfire

- Drew Taylor, WIAT-TV, Birmingham, Ala.: ‘Just Mercy,’ movie set in Alabama, makes $10 million at box office

- Bruce C.T. Wright, NewsOne: Don’t Believe The Hype: Black Men’s Unemployment Rate Jumps As Wages Keep Dropping

(More to come)

[btnsx id=”5768″]

Facebook users: “Like” “Richard Prince’s Journal-isms” on Facebook.

Follow Richard Prince on Twitter @princeeditor

Richard Prince’s Journal-isms originates from Washington. It began in print before most of us knew what the internet was, and it would like to be referred to as a “column.” Any views expressed in the column are those of the person or organization quoted and not those of any other entity. Send tips, comments and concerns to Richard Prince at journal-isms-owner@yahoogroups.com

View previous columns (after Feb. 13, 2016).

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2018 (Jan. 4, 2019)

- Book Notes: Is Taking a Knee Really All That? (Dec. 20, 2018)

- Book Notes: Challenging ’45’ and Proudly Telling the Story (Dec. 18, 2018)

- Book Notes: Get Down With the Legends! (Dec. 11, 2018)

- Journalist Richard Prince w/Joe Madison (Sirius XM, April 18, 2018) (podcast)

- Richard Prince (journalist) (Wikipedia entry)

- February 2018 Podcast: Richard “Dick” Prince on the need for newsroom diversity (Gabriel Greschler, Student Press Law Center, Feb. 26, 2018)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2017 — Where Will They Take Us in the Year Ahead?

- Book Notes: Best Sellers, Uncovered Treasures, Overlooked History (Dec. 19, 2017)

- An advocate for diversity in the media is still pressing for representation, (Courtland Milloy, Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2017)

- Morgan Global Journalism Review: Journal-isms Journeys On (Aug. 31, 2017)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2016

- Book Notes: 16 Writers Dish About ‘Chelle,’ the First Lady

- Book Notes: From Coretta to Barack, and in Search of the Godfather

- Journal-isms’ Richard Prince Wants Your Ideas (FishbowlDC, Feb. 26, 2016)

- “JOURNAL-ISMS” IS LATEST TO BEAR BRUNT OF INDUSTRY’S ECONOMIC WOES (Feb. 19, 2016)

- Richard Prince with Charlayne Hunter-Gault,“PBS NewsHour,” “What stagnant diversity means for America’s newsrooms” (Dec. 15, 2015)

- Book Notes: Journalists Follow Their Passions

- Book Notes: Journalists Who Rocked Their World

- Book Notes: Hands Up! Read This!

- Book Notes: New Cosby Bio Looks Like a Best-Seller

- Journo-diversity advocate turns attention to Ezra Klein project (Erik Wemple, Washington Post, March 5, 2014)

Columns below from the Maynard Institute are not currently available but are scheduled to be restored soon on journal-isms.com.

- Book Notes: “Love, Peace and Soul!” And More

- Book Notes: Book Notes: Soothing the Senses, Shocking the Conscience

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2015

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2014

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2013

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2012

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2011

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2010

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2009

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2008

- Book Notes: Books to Ring In the New Year

- Book Notes: In-Your-Face Holiday Reads

- Fishbowl Interview With the Fresh Prince of D.C. (Oct. 26, 2012)

- NABJ to Honor Columnist Richard Prince With Ida B. Wells Award (Oct. 11, 2012)

- So What Do You Do, Richard Prince, Columnist for the Maynard Institute? (Richard Horgan, FishbowlLA, Aug. 22, 2012)

- Book Notes: Who Am I? What’s Race Got to Do With It?: Journalists Explore Identity

- Book Notes: Catching Up With Books for the Fall

- Richard Prince Helps Journalists Set High Bar (Jackie Jones, BlackAmericaWeb.com, 2011)

- Book Notes: 10 Ways to Turn Pages This Summer

- Book Notes: 7 for Serious Spring Reading

- Book Notes: 7 Candidates for the Journalist’s Library

- Book Notes: 9 That Add Heft to the Bookshelf

- Five Minutes With Richard Prince (Newspaper Association of America, 2005)

- ‘Journal-isms’ That Engage and Inform Diverse Audiences (Q&A with Mallary Jean Tenore, Poynter Institute, 2008)

![]()

31 comments