How Journalists Can Get Beyond the Soundbites

Homepage photo from Twin Cities PBS documentary, “Slave Labor’s Money Built Minnesota. How Do We Make Reparations?”

Journal-isms Roundtable photos by Sharon Farmer/sfphotoworks

Support Journal-ismsDonations are tax-deductible.

How Journalists Can Get Beyond the Soundbites

By Isaiah J. Poole

As the demand for reparations for the impact of slavery and institutional racism moves from rhetoric to real proposals and programs, supporters are differing over what actually counts as “reparations.”

That makes covering the issue challenging for journalists who want to get beyond the soundbites to the serious questions about how the United States should reckon with its racial legacy.

As far back as 1970, poet and musician Gil Scott-Heron was raising deep and provocative questions about the subject.

“Many suggestions and documents written, many directions for the end that was given,” he sang. “They gave us pieces of silver and pieces of gold; tell me, who’ll pay reparations on my soul?”

That song — “Who’ll Pay Reparations on My Soul?” (video) — became the theme of a wide-ranging discussion at the Jan. 30 Journal-isms Roundtable.

Forty-four people were on the Zoom. By March 5, another 278 had watched on Facebook and 110 more on YouTube. You may watch the video embedded below or on the YouTube site.

The question came up again in the Roundtable’s Feb. 19 session with Rep. James Clyburn, D-S.C., assistant House Democratic leader. Clyburn said he is trying to achieve results by avoiding the term “reparations.” The congressman has introduced a bill to provide redress to African American veterans who were denied benefits under the G.I. bill. “For some strange reason, people say, ‘No, I don’t want the word “reparations” to be there.’ So if you’re waiting on that, keep waiting. It ain’t gon’ happen.” Clyburn said at another point, “So the question is, are you for reparations, or are you for the soundbite?”

Forty-four people were on the Zoom Journal-isms Roundtable held Jan. 30. By March 5, another 278 had watched on Facebook and 110 more on YouTube.

Alvin B. Tillery Jr., Ph.D., is a professor of political science and director of the Center for the Study of Diversity and Democracy. He is leading a study of reparations developments in Evanston, Ill., a suburb of Chicago. Tillery said Evanston’s program is focused narrowly on redressing historical housing discrimination. Proponents of the $10 million housing and economic development program “thought very carefully about making the program very targeted” to survive legal challenges.

Trahern Crews (pictured) is founder of Black Lives Matter Minnesota and member of the city council-created St. Paul Recovery Act Community Reparations Commission.

Trahern Crews (pictured) is founder of Black Lives Matter Minnesota and member of the city council-created St. Paul Recovery Act Community Reparations Commission.

In that jurisdiction, reparations thinking encompasses such contemporary issues as the impact of police violence and embracing international principles of reparations, including ending the repetition of harmful actions.

“Constantly, this repeat of discrimination, economic discrimination, continues to happen to Black Americans,” Crews said. “So when we talk about it, it won’t be hard to figure out the legalities of it; this is still happening. When you talk about loss of land, Black Americans have lost 90 percent of our land since 1910 or the Reconstruction period into 1997. . . . We’re not talking about slavery but we’re also talking about Jim Crow, we’re talking about the lynching period, we’re talking about redlining and redistricting, we’re talking about mass incarceration, and we’re talking about police terror.”

Nkechi Taifa (pictured), lawyer and reparations advocate who has just published “Reparations on Fire: How and Why it’s Spreading Across America,” agreed. Taifa chaired the Legislative Commission of the National Coalition Of Blacks for Reparations in America, known as N’COBRA. That group determined five “injury areas” that it believes are able to survive arguments that the statute of limitations has expired. The areas are the Black vs. white wealth gap, “peoplehood/nationhood,” which includes “the destruction of African people’s culture,” education, criminal punishment and health disparities.

Nkechi Taifa (pictured), lawyer and reparations advocate who has just published “Reparations on Fire: How and Why it’s Spreading Across America,” agreed. Taifa chaired the Legislative Commission of the National Coalition Of Blacks for Reparations in America, known as N’COBRA. That group determined five “injury areas” that it believes are able to survive arguments that the statute of limitations has expired. The areas are the Black vs. white wealth gap, “peoplehood/nationhood,” which includes “the destruction of African people’s culture,” education, criminal punishment and health disparities.

Retired journalist Kenneth Walker attempted a different delineation. “We are tending to conflate two separate but very related legal issues: reparations, which is one continuing movement against a continuing battle against crimes against humanity against Black people, of which police terrorism is a most important component. While we pursue reparations for previous damages, we must continue to seek justice in criminal and civil courts, the judiciaries and other countries, including the U.N and the International Court of Justice.”

“I don’t think we’re saying anything different,” Taifa responded. “We say that the reparations are not just for the enslavement era before; it’s living legacies and mass incarceration.”

Rachel Swarns (pictured), journalist, journalism professor at New York University and author of the forthcoming “The 272: The Families Who Were Enslaved and Sold to Build the American Catholic Church,” said she has been examining the responses of faith institutions. “They’re taking a number of different approaches in terms of both the historical harm that they’re hoping to address and also the remedy that they’re proposing.”

Rachel Swarns (pictured), journalist, journalism professor at New York University and author of the forthcoming “The 272: The Families Who Were Enslaved and Sold to Build the American Catholic Church,” said she has been examining the responses of faith institutions. “They’re taking a number of different approaches in terms of both the historical harm that they’re hoping to address and also the remedy that they’re proposing.”

Georgetown University responded to reporting by Swarns in The New York Times that in 1838, slaves were sold to help keep the university solvent. Georgetown pledged to raise $400,000 a year that would be awarded to projects designed to benefit the communities of slave descendants. A first wave of grants is expected soon. A $100 million reparations effort by Jesuit priests, however, is struggling to raise the promised funding. That money would go to a newly formed foundation established in conjunction with descendants.

Meanwhile, the Virginia Theological Seminary, an Episcopal institution, is issuing checks of about $2,100 a year to descendants of slaves exploited by the seminary, as well as to Black people affected by the seminary’s complicity with Jim Crow-era discrimination. “So there’s a lot of experimentation, thinking and arguing about how this should play out,” Swarns said.

Katie Galioto (pictured) of the Star Tribune in Minneapolis, who has been covering the city government there for two years, said, “The word reparations means very different things to very different people in the community.” Some advocates are talking about ”direct cash payments to all Black descendants of slaves.”

Katie Galioto (pictured) of the Star Tribune in Minneapolis, who has been covering the city government there for two years, said, “The word reparations means very different things to very different people in the community.” Some advocates are talking about ”direct cash payments to all Black descendants of slaves.”

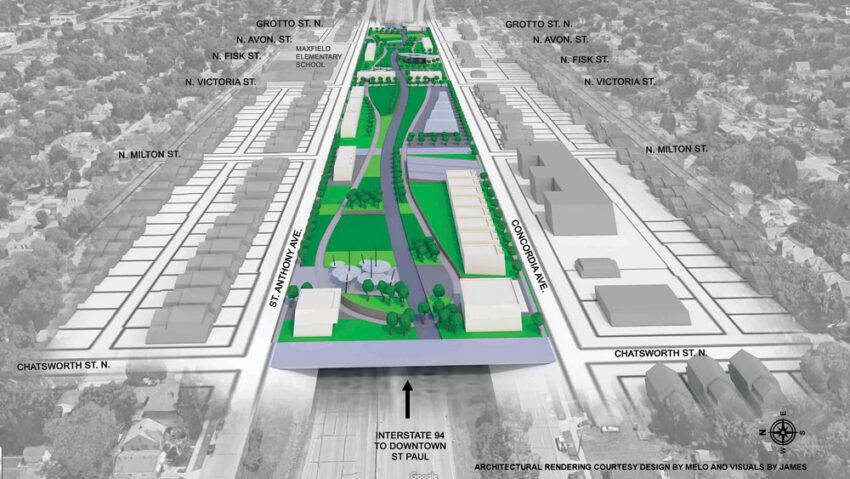

Others, including St. Paul Mayor Melvin Carter (pictured), who is African American, are advocating a more targeted approach, such as a housing loan fund he calls The Inheritance Fund. It is designed to address the historically Black neighborhood of Rondo, where hundreds of homes and businesses were razed nearly 60 years ago to make room for a freeway.

Others, including St. Paul Mayor Melvin Carter (pictured), who is African American, are advocating a more targeted approach, such as a housing loan fund he calls The Inheritance Fund. It is designed to address the historically Black neighborhood of Rondo, where hundreds of homes and businesses were razed nearly 60 years ago to make room for a freeway.

“Something I think that’s really interesting is [Carter] has really been intentionally trying to distinguish this program from reparations,” Galioto said. “The Rondo community, he says, lost $100 million in generational wealth when this freeway was built. He sort of told me recently in an interview that ‘I’m not using the word reparations because what we’re doing is nowhere near a $100 million repayment and his focus is starting to rebuild some of these inheritances that were lost.’”

Ellis Cose (pictured), journalist and author of “Race and Reckoning: From Founding Fathers to Today’s Disruptors,” opened the discussion by tracing the roots of reparations to what is popularly known as the promise of “40 acres and a mule” to enslaved Black people after the Civil War.

Ellis Cose (pictured), journalist and author of “Race and Reckoning: From Founding Fathers to Today’s Disruptors,” opened the discussion by tracing the roots of reparations to what is popularly known as the promise of “40 acres and a mule” to enslaved Black people after the Civil War.

“You can’t really talk about reparations without talking about General William Sherman’s Special Order No. 15, which basically laid out a plan to divide among former enslaved people — freed men — land that he had taken in his Grand March through the South,” Cose said. But that order was blocked by President Andrew Johnson, who had also vetoed the Civil Rights Bill of 1866, which conferred upon former slaves born in the United States the “full and equal benefit” of U.S. citizenship.

Cose fast-forwarded to 1969, when James Forman, then a leader in the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, endorsed a demand for $500 million in reparations. Twenty years later, Michigan Rep. John Conyers would introduce the first of a series of bills in successive sessions of Congress — usually numbered H.R. 40 to echo Sherman’s 40-acres order — calling for a commission to study and develop a national reparations plan.

“I actually had sat down on several occasions with Conyers and asked him about this project, which seemed rather futile, quite frankly, and asking why he kept doing it, and he said he thought it was important that the issue be raised, and he’s absolutely right,” Cose said.

Cose also pointed out that reparations did not always have majority support among Black Americans. A 1969 Gallup poll found that a slight majority of Black people were actually opposed to the concept, Cose said. On the other hand, the white opposition was overwhelming; only 2% of white poll respondents said they favored it.

A November 2021 poll by the Pew Research Center, however, found that 77 percent of Black Americans supported reparations for the descendants of enslaved people, while support among white people increased from 2 percent to 18 percent.

The reparations movement draws some inspiration from the successful reparative justice actions on behalf of Japanese Americans affected by the federal government’s internment actions during World War II. Ruben Navarrette Jr., a native Californian, researched the Japanese internment for his column, distributed by the Washington Post Writers Group. Navarrette told the Roundtable, “You have to understand that the parallel here in many cases is that the internment wasn’t just about interning the Japanese; it was about stealing their land.”

Jon Funabiki, who has long been a journalism diversity champion, said there is widespread support among his fellow Japanese Americans for African American reparations, but that there are key differences:

Reparations for Japanese Americans were for a single injustice — their “incarcerations during World War II,” and that redress was limited to the descendants of those who were placed in captivity. When migrant children were held at the Mexico-U.S. border during the Trump administration, he said, Japanese Americans who were children during the incarceration went there to lend support.

California has created a Reparations Task Force that is scheduled to submit recommendations to the state legislature by July 1. That is where the issues get more complicated, according to Navarrette.

“There was an interesting debate that some of you may have seen within the commission, African Americans within the commission arguing with other African Americans on the commission, and the issue was whether the reparations should be limited to Black people who were in the United States as of the 19th century, whether they were freed or enslaved, or whether it should be broader. They basically said, ‘No, these should be limited to people who were here, not recent arrivals,’ and maybe now there’s a debate also about when you got to California. So there’s a discussion there, sort of the devil is in the details, in terms of limiting it and who gets it. . . . I was struck by just how sweeping the discussion became.”

Navarrette (pictured, below) wrote a column opposing a reparations initiative on behalf of Mexican Americans, whose ancestors had land stolen from them and treaty agreements broken when the United States seized their land in 1848.

“Victimization doesn’t mean that I think of myself as a victim, and it also means that Mexican Americans are never — I promise you — they’re never going to come forward and make a demand for reparations,” Navarrette said. “It’s not in our DNA to do that and I think one reason is, from all I hear, we don’t believe that there’s a price to be put on us. We don’t believe that there’s a price that the state of California can give us to shut us up and buy us off, because there just isn’t. We don’t think that this can be made right in that way.”

“Victimization doesn’t mean that I think of myself as a victim, and it also means that Mexican Americans are never — I promise you — they’re never going to come forward and make a demand for reparations,” Navarrette said. “It’s not in our DNA to do that and I think one reason is, from all I hear, we don’t believe that there’s a price to be put on us. We don’t believe that there’s a price that the state of California can give us to shut us up and buy us off, because there just isn’t. We don’t think that this can be made right in that way.”

Navarrette was echoing the sentiments of Harvard professor Jesse McCarthy, an African American who titled a book of essays after Scott-Heron’s “Who’ll Pay Reparations” song. McCarthy wrote, “Injustice has an affective, emotional dimension that is deeply corrosive, but which can never be quantified.”

Melvin B. Miller, who just retired as publisher of Boston’s Bay State Banner, offered a different argument: “Boston Blacks must not tolerate the insult that they are still impaired by the hostile infliction of slavery that ended 239 years ago,” he editorialized in December.

Funabiki, a retired journalism professor at San Francisco State University, concluded, “I’ve really learned so much by just listening to this conversation and I can really see the need for some guidelines for journalists about how to cover this.

“Having something that we that journalists can use to help guide them as they cover these issues and see the differences between the way people are using the term and using other terms, whether it’s reparations, reconciliation — these are totally different things. Social justice reforms, criminal justice reforms, these are all very separate things and we are tending to glom them all together as we cover this issue.”

Said Navarrette, “The most important thing we have going for us as journalists — I’ve been doing this over 35 years — is critical thinking. Thinking critically about things, being able to ask these questions. And I think as you look through the reparations issue, there should be lots of questions and even questions that reporters are asking themselves.

“We’ve talked about them here: What are reparations? What terms should we use? How do you define reparations?

“Why are reparations in place; to compensate or to punish, to acknowledge the past or somehow rectify the present?

“Who should be covered? We talked about that in California. If you’re a African American family in California that goes back four generations and you can show direct oppression by the state of California, who stole your land and then profited from it, should you not be more deserving of direct reparations than somebody who is an African American from Georgia who just moved to California last month?

“Is that conversation worth having? If you broaden it out and you bring in more African Americans, does that dilute the amount of money that goes to the native Californian African American? I don’t have an answer to that; these are the kinds of questions people should ask.”

- Kassidy Arena, KCUR. org: What would reparations for Black communities look like in rural Missouri? (Jan. 25)

- Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, Duluth News-Tribune: Refusing to repair the harm would cost even more than reparations

- Carrie Blazina and Kiana Cox, Pew Research Center: Black and White Americans are far apart in their views of reparations for slavery (Nov. 28, 2022)

- Church of the Brethren Newsline: General secretary signs interfaith letter on reparations

- Megan Cloherty, WTOP.com: DC lawmakers to reconsider paying reparations to African American residents (Feb. 27)

- Gabby Deutch, Jewish Insider: The U.S. diplomat seeking justice for Holocaust survivors (Jan. 24)

- Emmanuel Felton, The Washington Post: A Chicago suburb promised Black residents reparations. Few have been paid. (Jan. 9)

- Andy Fox, WAVY, Norfolk, Va.: How the federal government took land from hundreds of African Americans in order to build Naval Weapons Station Yorktown

- Callan Gray, KSTP.com: St. Paul City Council establishes permanent reparations commission (Jan. 5)

- Janie Har, AP: Japanese Americans won redress, fight for Black reparations (Feb. 24)

- Alex Lenferna, Daily Maverick, South Africa: Does South Africa deserve climate reparations? (Jan. 24)

- Alicia Victoria Lozano, NBC News: Tennessee’s largest county to study reparations for descendants of enslaved people (Feb. 22)

- Marcus D. Smith, The Sacramento Bee: It’s California residents’ last chance to publicly weigh in on reparations. Here’s how

- Taylor Thompson, WLOS.com: ‘I want to make a change’ Storytellers share passion for documenting reparations process (Feb. 27)

- TVP World: We call on EU Council for resolution on WWII reparations from Germany: official (Jan. 26)

- Jesse Washington, andscape: Reparations coverage

- Tim Williams and Nick Reisman, Spectrum News 1: New York slavery reparations bill sponsor is hopeful for passage in 2023 (Feb. 21)

To subscribe at no cost, please send an email to journal-isms+subscribe@groups.io and say who you are.

Facebook users: “Like” “Richard Prince’s Journal-isms” on Facebook.

Follow Richard Prince on Twitter @princeeditor

Richard Prince’s Journal-isms originates from Washington. It began in print before most of us knew what the internet was, and it would like to be referred to as a “column.” Any views expressed in the column are those of the person or organization quoted and not those of any other entity. Send tips, comments and concerns to Richard Prince at journal-isms+owner@

View previous columns (after Feb. 13, 2016).

View previous columns (before Feb. 13, 2016)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2018 (Jan. 4, 2019)

- Book Notes: Is Taking a Knee Really All That? (Dec. 20, 2018)

- Book Notes: Challenging ’45’ and Proudly Telling the Story (Dec. 18, 2018)

- Book Notes: Get Down With the Legends! (Dec. 11, 2018)

- Journalist Richard Prince w/Joe Madison (Sirius XM, April 18, 2018) (podcast)

- Richard Prince (journalist) (Wikipedia entry)

- February 2018 Podcast: Richard “Dick” Prince on the need for newsroom diversity (Gabriel Greschler, Student Press Law Center, Feb. 26, 2018)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2017 — Where Will They Take Us in the Year Ahead?

- Book Notes: Best Sellers, Uncovered Treasures, Overlooked History (Dec. 19, 2017)

- An advocate for diversity in the media is still pressing for representation, (Courtland Milloy, Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2017)

- Morgan Global Journalism Review: Journal-isms Journeys On (Aug. 31, 2017)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2016

- Book Notes: 16 Writers Dish About ‘Chelle,’ the First Lady

- Book Notes: From Coretta to Barack, and in Search of the Godfather

- Journal-isms’ Richard Prince Wants Your Ideas (FishbowlDC, Feb. 26, 2016)

- “JOURNAL-ISMS” IS LATEST TO BEAR BRUNT OF INDUSTRY’S ECONOMIC WOES (Feb. 19, 2016)

- Richard Prince with Charlayne Hunter-Gault, “PBS NewsHour,” “What stagnant diversity means for America’s newsrooms” (Dec. 15, 2015)

- Book Notes: Journalists Follow Their Passions

- Book Notes: Journalists Who Rocked Their World

- Book Notes: Hands Up! Read This!

- Book Notes: New Cosby Bio Looks Like a Best-Seller

- Journo-diversity advocate turns attention to Ezra Klein project (Erik Wemple, Washington Post, March 5, 2014)