Racist Contexts Must Be Part of the Story

[btnsx id=”5768″]

Racist Contexts Must Be Part of the Story

On Jan. 6, a day that will live in infamy, a man in full “Make America Great Again” regalia was pushing an older white woman in a wheelchair past Washington, D.C.’s historically Black Metropolitan AME Church. In front of the church’s security deployment, the woman said, “We’re here because we hate niggers,” according to the pastor.

The MAGA folks may dress up their cause in lofty themes of liberty, freedom and democracy, said the Rev. William H. Lamar IV (pictured, photos by Sharon Farmer/sfphotoworks), but the woman bluntly put the Capitol riot in context.

The MAGA folks may dress up their cause in lofty themes of liberty, freedom and democracy, said the Rev. William H. Lamar IV (pictured, photos by Sharon Farmer/sfphotoworks), but the woman bluntly put the Capitol riot in context.

The line is direct between vicious antebellum slave patrols and present-day police departments, between burnings of Black churches in days past and the torching of “Black Lives Matter” banners at Black churches today. Past is prologue.

But journalists don’t always make those connections, and the fight for diversity in newsrooms is in part to be sure that those who do connect those dots have a voice at the table. As the Los Angeles Times Guild Black Caucus declared last June, “Often, our framing and selection of stories is designed mostly with a white audience in mind at the expense of communities of color . . .”

Lamar and the Rev. Ianther Mills (pictured) of Asbury United Methodist Church, pastors of the two Black churches in Washington whose “Black Lives Matter” banners were set afire in December, spoke Feb. 7 at a Zoom session of the Journal-isms Roundtable.

Lamar and the Rev. Ianther Mills (pictured) of Asbury United Methodist Church, pastors of the two Black churches in Washington whose “Black Lives Matter” banners were set afire in December, spoke Feb. 7 at a Zoom session of the Journal-isms Roundtable.

So did Jon Funabiki, longtime diversity advocate who just retired as journalism professor at San Francisco State University and as director of the Renaissance Journalism Project. He and his successor, Valerie Bush, said their Oakland-based project aims “to get journalists to think about the way they frame stories; to think about the equity and social justice implications,” as Funabiki said.

The discussion was wedged between the attack on the Capitol, where five died and more than 140 were injured, the inauguration of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, and the Senate trial in the impeachment of Donald J. Trump, which ended with Trump’s acquittal.

Seventy-two people were on the Zoom call, and upwards of 370 watched on Facebook. The video can be seen here.

Joining were Susan Corke, who tracks hate crimes and hate groups for the Southern Poverty Law Center, George Derek Musgrove, co-author of the book “Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital,” whose latest project tracks the major Black Power events and organizations in Washington, and Toriano Porter, editorial writer at the Kansas City Star, who gave us a brief update on the Star’s efforts at redressing its racial past. Those efforts included a full-throated apology.

“It was an obvious attempt at intimidation,” Mills said of the banner-burning at her church. “It was deliberate and planned. It was allegedly out of an anti-Black Lives Matter movement ideology but . . . most certainly it was out of racism, although the Proud Boys denied that. The attacks on our churches were more destructive and violent than those of white churches that also lost banners that December weekend. . . . I also see this as a rise in white supremacy and a sign that church burnings may be possible in this climate that we are currently living in.”

The late Toni Morrison tells Charlie Rose, “It’s as though our lives have no meaning, no depth without the white gaze.” That has no place in any of her books, she said. (video)

Lamar told the Roundtable that “History may not repeat itself, but it does have patterns. So, what I’m looking for is, when you write about a church burning, how can you tie that into what happened at Wilmington [N.C.], what happened in Tulsa and the work that Dr. [Julianne] Malveaux,” economist and columnist, has done on the intersection of economics and race.

“This stuff is built around economics,” Lamar said. “This stuff is about — you criticize me for not achieving, and when I achieve, you kick me, you burn my stuff down, you destroy my community. So what I’m looking for is context. When we talk about the filibuster, we’ve got to understand, it started with John C. Calhoun and a cold racist who is roasting in hell right now — if there is such a physical place, I’m not so sure, but he used a talking filibuster, beginning in the 1850s, when it looked like slavery was losing its political protection, and then his political progeny, Strom Thurmond, he used the same thing.

“It was used time and time again to shore up white supremacy and to stop anything that looks like democracy. That is a story that has to be told. Don’t just talk about the filibuster out of the blue as if it has no historical analog and as if it — it is the same thing. They will use it today (to stop) COVID relief. That is akin, if they could, to shoring up enslavement and keeping Jim Crow strong. It is keeping the resources of the government from the most vulnerable.

“It is keeping the status quo in place. So what I am looking for from journalists — I know it’s difficult ’cause you don’t have a lot of words and the American public is — I hate to say this, but so dumbed down . . . I know you all are smart enough to figure out that this is not a new thing and the way that Mitch McConnell is using it today is the way that John Calhoun used it. For the similar purpose of keeping anything that looks like democracy from flourishing.

“Those are the kind of stories, so that maybe it might serve to wake us up.”

Lamar, who is among those seeking a doctorate in African American Preaching and Sacred Rhetoric, also provided a window into the worldview of liberation theology, a perspective too little discussed in mainstream media: Is the United States a “democracy,” given successful efforts at voter suppression, or an “aspiring” democracy?

Do white evangelicals really share the same religion as himself and other Christians? Or is it the case that “the God of the enslaved is not the God of the enslaver. . . American Christianity is the carrier of white supremacy,” Lamar asserted. “I am unwilling to pretend that the God of Billy Graham and Jerry Falwell is the God of Jeremiah Wright.”

Noting that journalists “have in mind a world when you write,” Lamar added that journalism “assumes the universality of whiteness. Whiteness, or what Toni Morrison would call that gaze, that normative white gaze (video). I will be asked about the Black church being political, but they will not ask Robert Jeffers,” a white Southern Baptist pastor, broadcaster and Fox News contributor, the same thing. Theirs is “the politics of the status quo. And they will support the status quo with violence. As did their fathers and their mothers before them.”

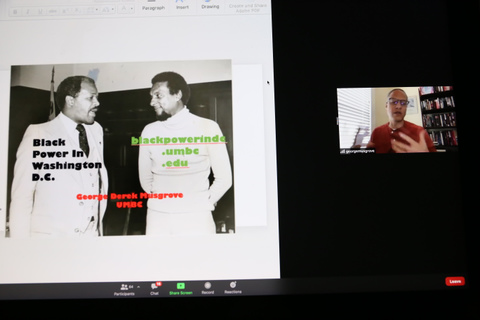

D.C.’s own fathers and mothers, and their children, might benefit from Musgrove’s (pictured) retrospective of the Black Power era. As Musgrove showed photos of Stokely Carmichael, later Kwame Ture, Malcolm X and the late D.C. mayor Marion Barry, the historian bemoaned the failure of The Washington Post to make its photo archives available to researchers.

D.C.’s own fathers and mothers, and their children, might benefit from Musgrove’s (pictured) retrospective of the Black Power era. As Musgrove showed photos of Stokely Carmichael, later Kwame Ture, Malcolm X and the late D.C. mayor Marion Barry, the historian bemoaned the failure of The Washington Post to make its photo archives available to researchers.

“I think that’s a shame for the people of the city, who should know more about this movement,” he said, returning to the issue of context. By coincidence, The Post’s Robert McCartney wrote the next day of Musgrove’s feeling that the philosophy of city leaders from the activist past, committed to empowering poor, marginalized African American communities, had been “set aside” in favor of gradual, market-oriented policies that have been “tremendously bad for the poor” and created an “explosion of inequality.”

Kris Coratti, spokesperson for the Post, messaged Journal-isms, “We’ve actually never allowed outside researchers to access the print photo archive.” She did not say why.

Funabiki and Bush said their multicultural upbringings helped lead to their passions for journalism.

In East Palo Alto, Calif., Funabiki (pictured below), said, “My high school was approximately 70 to 80 percent African American, then Latino, primarily Mexican American, then a smattering of Japanese, Chinese and Filipinos. It was the best experience I could ever imagine. Because growing up in a multicultural environment, we didn’t even realize it, what we were experiencing at the time.

“My class, the Class of ’67, has had many reunions since then. The groups that come back all say, whether they’re white, Black, Asian, Latino, all say that they would never have traded that experience. And that it has shaped their lives, shaped their thinking, and it certainly shaped my thinking about equity and racial injustice, and therefore shaped the way I think about journalism, and so that’s kind of the root of why I do what I do.”

“My class, the Class of ’67, has had many reunions since then. The groups that come back all say, whether they’re white, Black, Asian, Latino, all say that they would never have traded that experience. And that it has shaped their lives, shaped their thinking, and it certainly shaped my thinking about equity and racial injustice, and therefore shaped the way I think about journalism, and so that’s kind of the root of why I do what I do.”

Bush (pictured), a Chinese-American of Eurasian background, was raised in the predominantly Mexican-American and white La Puente, Calif., and was often the only Asian American.

Bush (pictured), a Chinese-American of Eurasian background, was raised in the predominantly Mexican-American and white La Puente, Calif., and was often the only Asian American.

“I think I’m so happy that I had this experience,” Bush said. “I don’t understand why we don’t see the richness of learning from each other . . . and our communities and our cultures, and how much more powerful we are when we work together. So, like when AAJA [the Asian American Journalists Association] started to work on Unity, it was, to me, such a natural thing to think, why don’t the different minority journalism associations, for example, work together, and in fact celebrate the differences, which I thought in fact were kind of fun to see, actually.

“I think it’s shaped my values; it definitely shaped my passion for journalism, for storytelling . . . to capture the stories of people I often felt whose stories were not being told.”

On Dec. 20, the Kansas City Star published a series investigating its own history of how it covered — and failed to cover — Black residents over its 140-year history. Two weeks before the Roundtable, Porter (pictured), had moderated a community discussion of next steps.

On Dec. 20, the Kansas City Star published a series investigating its own history of how it covered — and failed to cover — Black residents over its 140-year history. Two weeks before the Roundtable, Porter (pictured), had moderated a community discussion of next steps.

“The work starts now for us,” Porter told the Roundtable. “With reconciliation comes actions. We’ve admitted to our past coverage of the Black community and how it hurt us, played into stereotypes; now what’s the course of action now. Challenged my managing editor and my president to make tangible action, so I’m hoping to see more diversity in the reporting ranks, more diversity in the recruiting ranks when it comes to interns, and definitely more minority voices and diverse voices when it comes to managerial and editing positions ’cause we lack that there, so we’re on the clock.”

Not everyone felt obligated to speak. Ricardo A Hazell Sr., who writes for The Shadow League, a website on sports and racial issues, was a first-time attendee who shared his observation with his Facebook followers.

“So, yesterday I was on Richard Prince Journal-isms Roundtable with the likes of Dr. Julianne Malveaux, Rev. William H. Lamar IV and a whole slab of heavy hitters in journalism, social justice think tanks and activism. Really felt good to just be in the room honestly. . . .”

- Elizabeth Dias, New York Times: Century Ago, White Protestant Extremism Marched on Washington

- Hamil Harris, Trice Edney Wire: “The Black Church v. The Proud Boys.”DC pastors say racist vandalism to their churches is part of a deeper problem | Greene County Democrat

- United Methodist Church: De-Colonizing the Church: A Commitment to Anti-Racism

[btnsx id=”5768″]

To subscribe at no cost, please send an email to journal-isms+subscribe@groups.io and say who you are.

Facebook users: “Like” “Richard Prince’s Journal-isms” on Facebook.

Follow Richard Prince on Twitter @princeeditor

Richard Prince’s Journal-isms originates from Washington. It began in print before most of us knew what the internet was, and it would like to be referred to as a “column.” Any views expressed in the column are those of the person or organization quoted and not those of any other entity. Send tips, comments and concerns to Richard Prince at journal-isms+owner@

View previous columns (after Feb. 13, 2016).

View previous columns (before Feb. 13, 2016)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2018 (Jan. 4, 2019)

- Book Notes: Is Taking a Knee Really All That? (Dec. 20, 2018)

- Book Notes: Challenging ’45’ and Proudly Telling the Story (Dec. 18, 2018)

- Book Notes: Get Down With the Legends! (Dec. 11, 2018)

- Journalist Richard Prince w/Joe Madison (Sirius XM, April 18, 2018) (podcast)

- Richard Prince (journalist) (Wikipedia entry)

- February 2018 Podcast: Richard “Dick” Prince on the need for newsroom diversity (Gabriel Greschler, Student Press Law Center, Feb. 26, 2018)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2017 — Where Will They Take Us in the Year Ahead?

- Book Notes: Best Sellers, Uncovered Treasures, Overlooked History (Dec. 19, 2017)

- An advocate for diversity in the media is still pressing for representation, (Courtland Milloy, Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2017)

- Morgan Global Journalism Review: Journal-isms Journeys On (Aug. 31, 2017)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2016

- Book Notes: 16 Writers Dish About ‘Chelle,’ the First Lady

- Book Notes: From Coretta to Barack, and in Search of the Godfather

- Journal-isms’ Richard Prince Wants Your Ideas (FishbowlDC, Feb. 26, 2016)

- “JOURNAL-ISMS” IS LATEST TO BEAR BRUNT OF INDUSTRY’S ECONOMIC WOES (Feb. 19, 2016)

- Richard Prince with Charlayne Hunter-Gault,“PBS NewsHour,” “What stagnant diversity means for America’s newsrooms” (Dec. 15, 2015)

- Book Notes: Journalists Follow Their Passions

- Book Notes: Journalists Who Rocked Their World

- Book Notes: Hands Up! Read This!

- Book Notes: New Cosby Bio Looks Like a Best-Seller

- Journo-diversity advocate turns attention to Ezra Klein project (Erik Wemple, Washington Post, March 5, 2014)

.

![]()